Communication is a clinical skill (part 3)

Written by Miguel Ángel Díaz, Iván López Vásquez, Cindy Adams and Antje Blättner

Asking owners open-ended questions, especially at the beginning of a consultation, is extremely important to improve not just communication in general, but also to ensure the veterinary practitioner takes the animal’s history effectively.

Article

Key Points

Open-ended questions are designed to introduce an area of inquiry without shaping the content.

Open questions

In thinking about the first part of the veterinarian-client interaction it’s important to consider three objectives. First, we want to know what the client wants to discuss, then add anything that the veterinarian wants to add, and plan with the client how to approach the rest of the consultation. The second objective involves establishing initial rapport and ensuring that the client feels like she is part of the process going forward. The third objective is to gauge how the client and the patient are doing given the circumstances. You might be wondering how best to address all three objectives given the need to be efficient. What we know from research to date is that vet practitioners tend to shy away from open-ended questions at the beginning of the consultation in favor of asking a series of closed questions:

- “Is he eating?”

- “Is he drinking?”

- “Is her pee and poop normal?”

- “Did you give her the medication?”

- “Are you getting her out for a walk?”

- “Did you make a decision?”

Research also reports that on average, veterinarians interrupt clients within 15.3 seconds of them starting to talk [1] and tell their story.

13 vs. 2: on average, vets ask 13 closed-ended questions and only 2 open-ended questions during a consultation

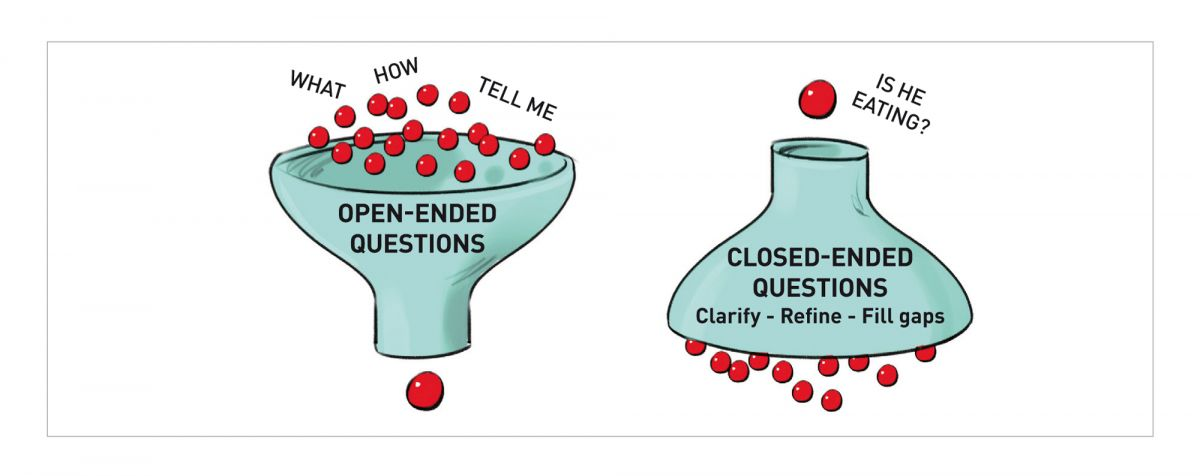

Closed-ended questions are questions for which a specific and quite often a one word answer such as yes or no, is desired. Clients usually provide a one or two word response without elaboration. The veterinarian has to follow each closed question with another, forcing their mind away from the client’s responses into diagnostic reasoning and prematurely forcing the discussion onto one particular area. This can interfere with listening, hearing important information and establishing a relationship.

Communication research reports that veterinarians generally ask 13 closed-ended questions and 2 open-ended questions per appointment (Figure 1). In 300 visits twenty-five percent of the veterinarians did not ask a single open-ended question [3]. A fully closed-ended approach can also increase the chances of “hidden concerns” arising at the end of the visit. The odds of a late arising concern are 4 times greater if a client is not invited or allowed to complete his story and let the vet practitioner know why he came to the practice with his pet 1. This fact has a profound impact on the length of appointments.

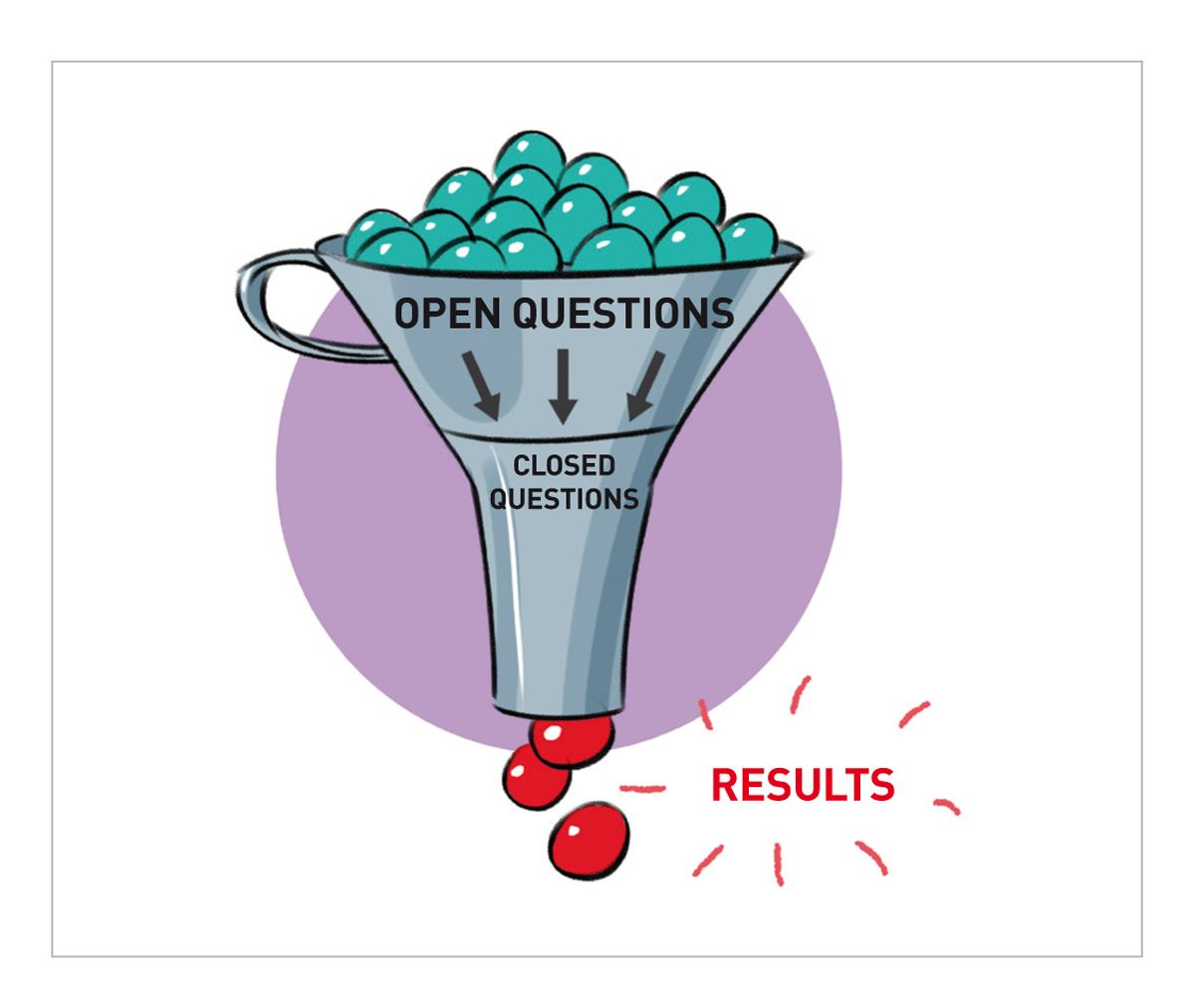

While there is no standard in terms of the exact number of open–ended questions that we should ask it is recommended that we structure our appointments in a funnel like fashion that includes starting open-ended and moving to more specific, direct closed-ended questions to clarify details or collect information that has not been reported through an open-ended inquiry. Given that 85% of the diagnosis comes from the history taking 4, it’s worth looking at the amount of open- to closed-ended questions that are being asked in any given appointment and work toward funneling the conversation starting with broad open-ended questions and then moving to closed or clarifying types of questions (Figure 2).

Near the beginning of the interview its important to ask the client open ended questions such as:

- “How can I help?”

- “Tell me what brings you and Molly in today?”

- “What would you like to talk about today?”

These types of questions allow the client to comment in broad terms about how their animal is doing but might not discover the actual problem that they have come about. On the other hand it might open up useful conversation with a client who shares that her cat’s been sleeping at the bottom of the stairs and she thinks this is happening because it’s so hot in his usual sleeping spot. While the change in the cat’s sleeping location might be related to the temperature there could also be other reasons for this behavior change. By virtue of asking a broad, open-ended question the vet practitioner better understands what the client is thinking which is critical to the development of a relationship.

Other options include retaining an open-ended question but steering it more directly to the patient.

For example:

- “Tell me what problems Ryder has been having since she was here last?”

- “How can I help you and Paisley?”

- “I have a letter from the referring veterinarian about what’s going on with Shadow, but please start by telling me what the problems are from your perspective.”

Open-ended questions are designed to introduce an area of inquiry without shaping the content. They still direct the client to a specific area but allow the client more range in how they answer, letting them know that elaboration is important and welcomed. It’s important to note that the average length of time that a client talks if they are not interrupted is 150 seconds 1.

15.3 seconds is the average time a pet owner can speak before being interrupted by the vet.

There is not a right or wrong open-ended question rather the question must be formulated according to the situation. There is however a need to raise our awareness and think carefully about we how they start each visit so to make room for the client to tell his story before moving on to more closed directive questions.

References

- Dysart LMA, Coe JB, Adams CL. Analysis of solicitation of client concerns in companion animal practice. JAVMA 2011;238(12):1609-1615.

- Bonvicini K. Bayer Animal Health Communication Project. Getting the Story: Understanding client and patient. New Haven (CT): Institute for Healthcare Communication, 2003.

- Shaw JR, Adams CL, Bonnett BN, Larson S, Roter DL. Use of the Roter interaction analysis system to analyze veterinarian-client-patient communication in companion Animal practice. JAVMA 2004;233(10):1576-1586.

- Henderson M, Tierney L, Smetana G. The Patient History: An Evidence-Based Approach to Differential Diagnosis, 2e. Mc-Graw Hill, New York 2012.

Miguel Ángel Díaz

DVM

Spain

Miguel received a degree in Veterinary Science in 1990. After working at several clinics he opened his own clinic in 1992 which grew from a two-person office to a 24/7 hospital with 17 employees. After running his hospital for 25 years, he handed it over to his team in 2017 in order to concentrate exclusively on his great passion: coaching.

Miguel is the director of the company New Way Coaching, aimed at helping veterinarians become better leaders. He has been educating and training veterinarians in Europe, Latin America, and Asia since 2009 in leadership, motivational techniques, effective communication, handling objections, conflict resolution, influence and persuasion. He spends his days giving individual coaching sessions, private training for his clients’ teams, and workshops and conferences for major veterinary sector companies.

Miguel is an International Coach Certified by the International Coaching Community and the Center for Executive Coaching (USA). He is a Certified Trainer for Edward de Bono’s Six Thinking Hats.

He has been an international speaker at conferences in over 10 countries on three continents. He is the author of the book “7 Keys to Successfully Running a Veterinary Practice”, which has been translated into English, Polish, Chinese and Italian.

Iván López Vásquez

DVM

Chile

Iván comes from a family of veterinarians; his father and older brother share the same passion. He obtained his degree from the Universidad de Concepción in 1991, worked a few years at a small clinic and then shifted his career towards sales and marketing, holding several positions at multinational companies in the domestic pet market in his native country.

Since 2008 he has been the executive director of Vetcoach, a business and organizational consulting company that specializes in the pet veterinary sector in Latin America, where his vision is to create “a new standard for the veterinary world”.

Iván has studied marketing, innovation, coaching and positive psychology. Today he is a strategic business consultant in organizational development and innovation, an ORA Coach (Organizational Role Analysis), creator of initiatives to improve the well-being (happiness) of veterinary students and qualified veterinarians, as well as high-value training programs for veterinary companies and their teams on subjects such as management, wellbeing, communication skills and positive leadership.

Iván has written several management articles for veterinary journals and is an international conference speaker in Latin America.

Cindy Adams

MSW, PhD

Canada

Cindy Adams is Professor in the Department of Veterinary Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences at the University of Calgary, Veterinary Medicine, where she developed and implemented the Clinical Communication Program in Calgary’s new veterinary school. She honed her professional understanding of human-animal relationships serving from 1980-1992 as a social worker in child welfare, women’s shelters and the justice system. Animals were frequently involved in that work. Combining the very different perspectives gained from her experiences in social work and a doctorate in veterinary epidemiology, she became a faculty member at the Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph (1996-2006). There she designed and directed the first veterinary communication curriculum in North America and pioneered a research program regarding communication in veterinary medicine.

She helped initiate the Institute for Healthcare Communication, Bayer veterinary communication project. Her research has focused on communication education, veterinary-client communication in large and small animal contexts, animal welfare, companion animal death and human grief. Founder of the International Conference on Communication in Veterinary Medicine, co-author of Skills for Communicating in Veterinary Medicine she has presented widely and advised veterinarians, veterinary practice teams and veterinary educators throughout North America, Europe, Australia and the Caribbean.

Antje Blättner

DVM

Germany

Dr. Blaettner grew up in South Africa and Germany and graduated in 1988 after studying Veterinary Medicine in Berlin and Munich. She started and ran her own small animal practice before undertaking postgraduate training and coaching course at the University of Linz, Austria and then founded “Vetkom”. The company provides training to veterinarians and veterinary nurses in practice management in subjects such as customer communication, marketing and other management topics. Dr. Blaettner also is editor for two professional journals, “Teamkonkret” (for veterinary nurses) and “Veterinärspiegel” (for veterinarians).

Other articles in this issue

Share on social media