Key challenges in the veterinary profession

The world brings challenges for the veterinary profession on a daily basis, and it can help to know that what we experience as individuals is shared by our colleagues, wherever they may be – and by understanding the challenges faced by other stakeholders we can work together in a way that is mutually beneficial.

Credit: Shutterstock

Article

Key Points

The veterinary profession is part of an ecosystem based around animal ownership that consists of many different stakeholders, all with different attitudes, aims and concerns.

The better we understand the different relationships between the stakeholders in the ecosystem, the more we can work together for the mutual benefit of all.

Working in practice inevitably produces tensions or “pain points” for most veterinarians, and these pain points are remarkably similar for veterinarians worldwide.

Being able to recognize and understand these challenges is the first step in coping with them, but it is also important to recognize the tensions and worries that other stakeholders experience.

Introduction

The world in which we live is changing rapidly, driven by many different factors, technologies and trials. In our own small microcosm change is inescapable. Although the main challenge we face as veterinarians – namely, the desire to enable animals to be as healthy and as happy as possible – has not altered since the profession was created, life for a veterinarian even twenty years ago was not the same as it is today, for many different reasons. And whilst today’s clinicians are unquestionably more knowledgeable about the animals they treat, and better equipped to tackle the diseases they combat than any generation before them, there is no escaping the fact that many of us find the daily workload stressful. Some will cope with this better than others, but the high dropout rate from the profession and the negative impact on the mental health of many veterinarians must serve as a warning that being an animal professional in the 21st century carries with it burdens as well as rewards.

Royal Canin recently commissioned a wide-reaching international survey to look in-depth at the world of cats and dogs today, and one of the areas researched was the problems and concerns – sometimes referred to as “pain points” – that are experienced by the various stakeholders involved in the domain of companion animals. This short article reviews some of the key findings as they relate to the veterinary side of things and suggests some positive ways ahead.

It is important to appreciate that clients have their own concerns and challenges, which will rarely match those of the clinician, and which are not always the ones that we as petcare experts might assume.

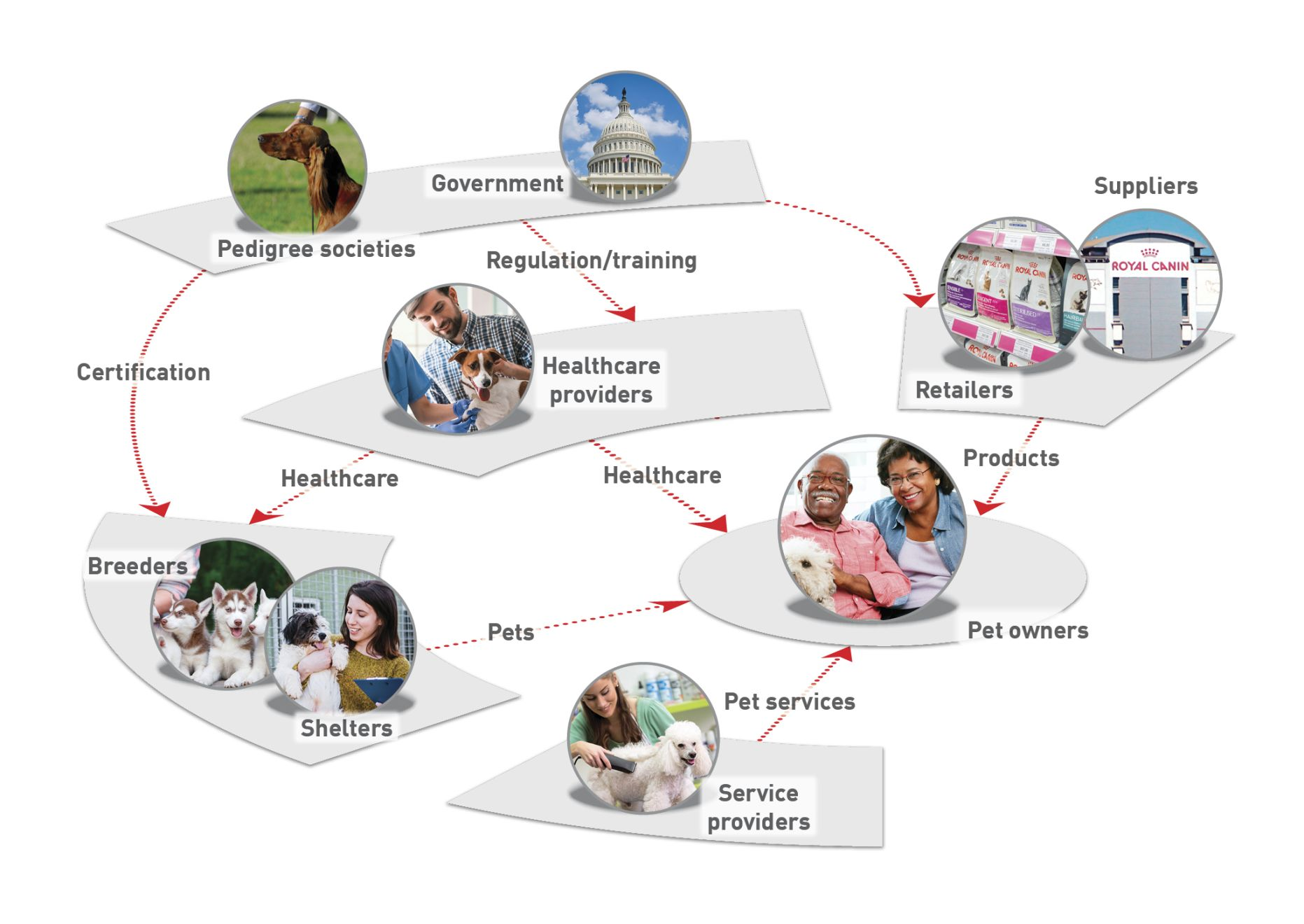

The pet owner “web”

The entire “ecosystem” or market sector that revolves around companion animals has various stakeholders, some of which are more apparent at first sight than others. The epicenter is, of course, the pet owner (typically an individual, a couple or a family unit) but they are interlinked with many other different, and sometimes conflicting, parties. A stakeholder may be defined as “a person or organization with an interest or concern in something, especially a business” – and this interest may be financial, regulatory or emotional in nature, or indeed a combination of these factors. So stakeholders in the community that exists around the pet owner will include not only veterinarians, but breeders, animal shelters, retailers and manufacturers (including pet shops, pet food companies and pet accessories), service providers (such as groomers and pet sitters), pedigree societies and – to a lesser extent – government departments (Figure 1).

The starting point is that each of us has our own view of the world; we will place ourselves at the center and see everything else revolving around us. The problem with this is that it can be difficult for one person to see the world from another person’s point of view. Each stakeholder will have their own perspective and motivations, and as they interact with other bodies and individuals, tensions or “pain points” can become evident in their relationships with each other. One way to counter this is to adopt the concept of the “economics of mutuality” – the idea being that since all the stakeholders within a sector are linked, we should strive to better understand each other’s attitudes, aims and concerns. If we can then work to defuse the tensions that inevitably arise in any relationship, this will ultimately be mutually beneficial for all concerned.

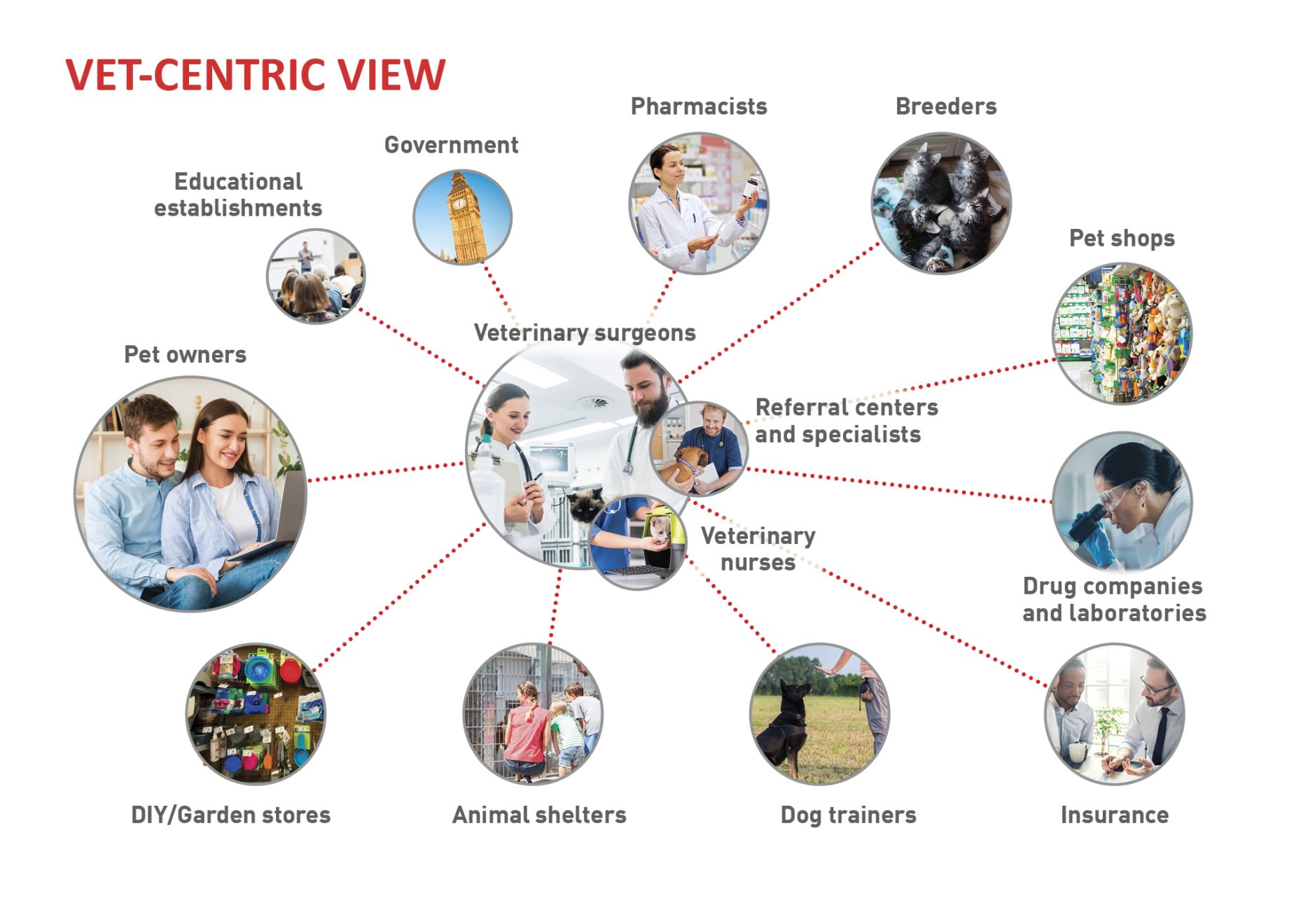

The pet-owner ecosystem was discussed briefly above, but each stakeholder in this network will also have their own ecosystem, again with different players and with different objectives, worries and aspirations. So in the veterinary world our set of stakeholders not only encompasses our clients and their animals, it also includes pharmaceutical and equipment companies, diagnostic laboratories, education establishments, and the veterinary support staff in our workplace (i.e., nurses, technicians and administration team) (Figure 2). The various relationships and interactions between these different groups will again bring its own conflicts and concerns.

Survey results

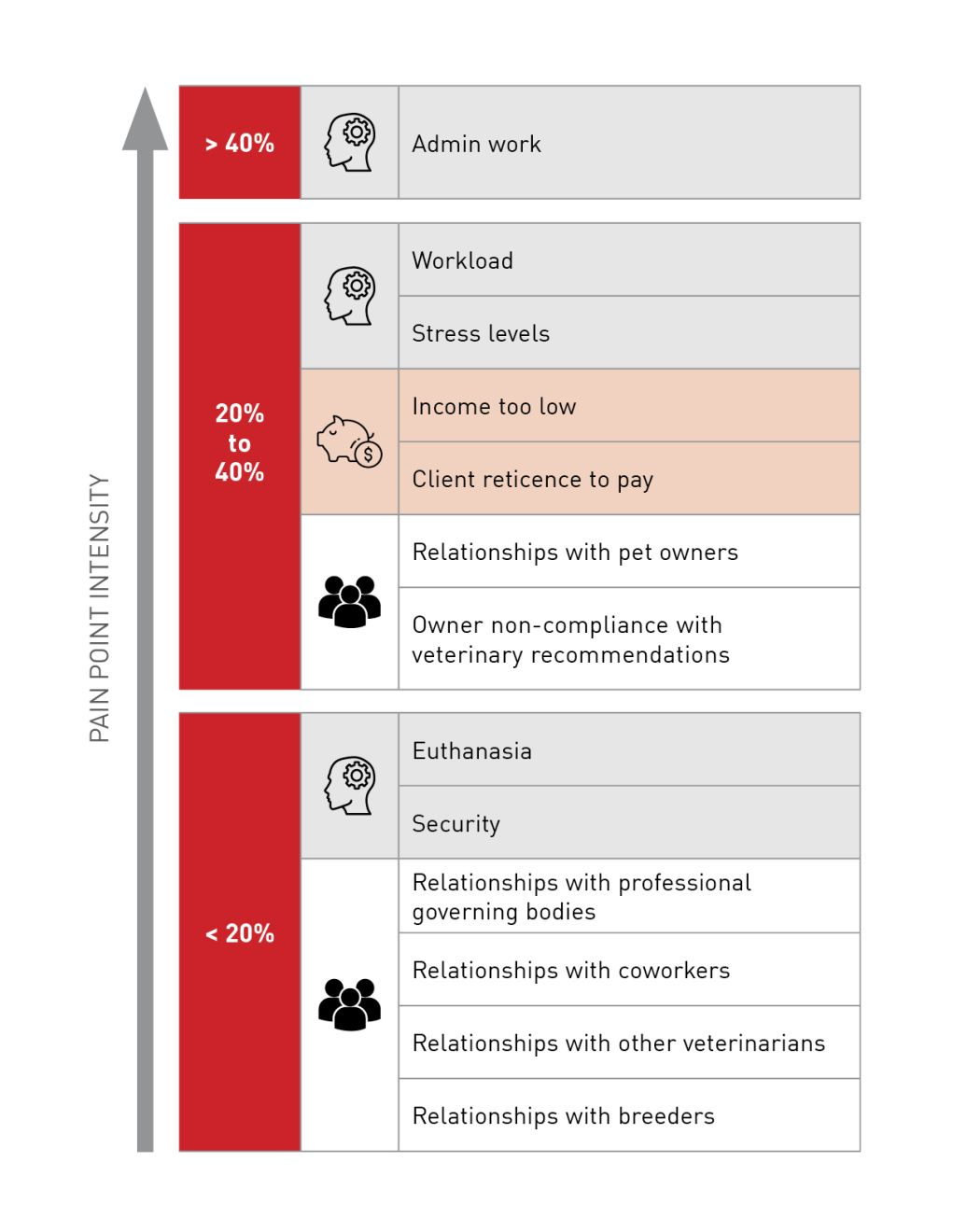

The survey involved a multi-faceted approach, but from our point of view it looked in depth at the veterinary world and our relationship with pets and their owners. The intention was to identify not only the major pain points that the different stakeholders have, but to analyze the problems raised, quantify them, and then help individuals and organizations to rationalize these challenges and adapt strategies to cope with them. 250 veterinarians from several different countries were involved (the USA, France, China, Thailand, Sweden, and Poland), and analysis of the results immediately revealed that the same tensions and stressors were common to veterinarians in all countries. These pain points could be categorized into three main groups – knowledge and personal health, financial, and relationships, and the major concerns raised within each of these categories were as follows:

- In the knowledge and health category, a lot of veterinarians identified tedious administration work as a prime problem; essentially, they find the high levels of paperwork and many of the necessary management tasks burdensome. Another major factor is the emotional toll of their work, which arises from undertaking difficult or stressful operations or dealing with animal death. The fact that many individuals feel they work “in isolation” – i.e., without significant support from their team or supervisor – was also cited, along with a generally high workload which involves long hours at the practice.

- Financial aspects included the fact that many veterinarians believe that they have a “bad deal” when it comes to employment – they feel that they are poorly rewarded for the long hours put in at college to cope with years of difficult study. Other factors included the idea that on-line competition for veterinary services and products is unfair, with many respondents saying that internet retailer prices were far too low. And a major problem is that the professional feels stressed when clients refuse treatment on the grounds of cost, possibly because pet owners perceive veterinary fees to be expensive, forgetting that a country’s national health service is funded either via taxes or health insurance, and that there is no equivalent for companion animals.

- When it comes to relationship problems, many veterinarians voiced the fact that their interaction with clients give rise to many concerns. Clinicians primarily want to deal with animals, not humans, and owners often do not listen to the advice being given. The rise of numerous “expert” websites and social media services – where anyone and everyone can voice an opinion, no matter how erroneous this may be – does not help; owners can arrive at the clinic already “informed” (or mis-informed) about their pet’s problem, and this can be perceived by the veterinarian as a challenge to their authority and status. Not only is this stressful for many professionals, as they believe that they should be accorded more respect by their clients, there is the additional concern that many owners do not appear to know how to take care of their pets or how to avoid basic mistakes in petcare.

More than 40% of all veterinarians surveyed said that administration was their main problem, whilst 20-40% cited various other reasons, including workload and stress, along with poor income and client willingness to pay.

The survey then quantified the different challenges, with respondents asked to rank their top two concerns, as shown in Figure 3. Overall, more than 40% of all veterinarians surveyed said that administration was their number one problem, whilst 20-40% cited various other reasons as their top cause for tensions encountered in their job. These included their overall workload and stress levels, low income and client reluctance to pay for their services, along with an unsatisfactory relationship with the pet owner – coupled with the latter’s poor compliance in following veterinary advice. Less than 20% of veterinarians cited relationships with other stakeholders (e.g., co-workers in the workplace or breeders), stress from performing euthanasia, or worries about their own security as major concerns. There was a strong consensus among petcare professionals that dealing with owners is often an ordeal, even if it is not the number one pain point for everyone.

In summary, the profession has a shared passion for animal welfare, but the challenge of delivering this successfully can lead to a great deal of tension for the individuals and teams in the clinic. Clinicians tend to be self-centered and status-focused, and many of us will have a limited customer service culture – running a business and dealing with humans are not always within our comfort zone. And for many of us the digital age is seen as a threat, not an opportunity. The overall conclusion is that we as veterinarians tend to have strained, imperfect relationships with many of our stakeholders.

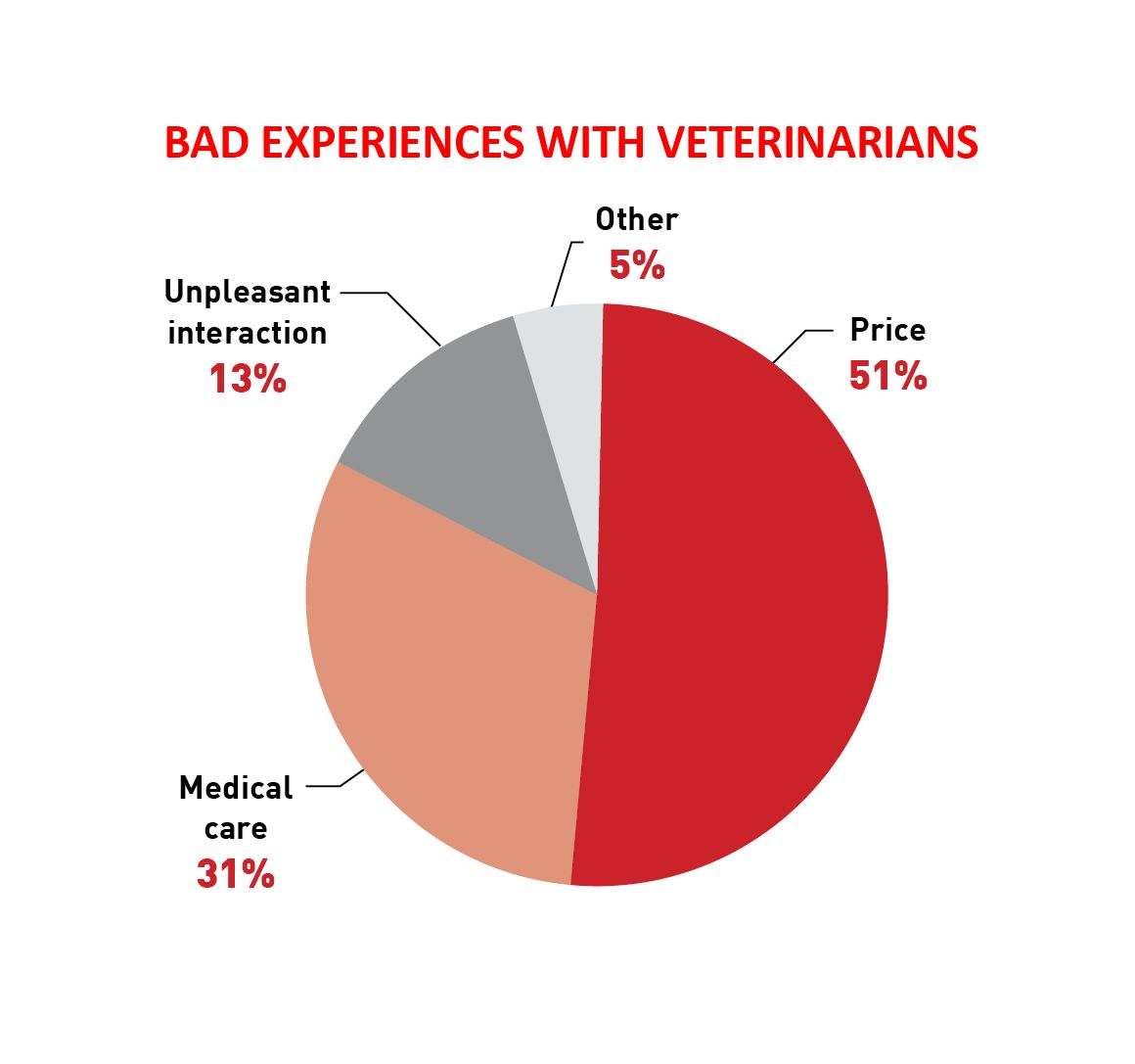

The pet owner

Before we go further it is also useful to consider the main tensions and concerns for pet owners as revealed by the survey, because it is important to appreciate that clients have their own worries and challenges which will rarely match those of the clinician, and which are not always the ones that we as petcare experts might assume (Figure 4). 800 owners were surveyed, and various common points emerged which can be put into the same three broad categories identified in the veterinary survey. At least some – but not all – of the owner concerns have some impact on the pain points experienced by the veterinary profession. One of the main issues – for between 50-70% of all owners surveyed – were the worries regarding the cost of owning a pet (including veterinary fees). Tellingly, 16% of owners questioned said that they had had a bad experience with a veterinarian within the last three years, and over 50% of these were related to costs (Figure 5). Various lifestyle constraints also come high on the list of worries – for example, the guilt an owner feels when leaving their pet at home while they are at work, along with the general hassle generated by the daily routine of owning a pet.

Other anxieties also emerged; these included worries about their pet in relation to holidays (either from concerns about transport, kenneling or holiday accommodation), which were cited by 30-50% of respondents, whilst anticipated guilt from potential damage caused by their pet, or embarrassment caused by their pet’s behavior (including complaints from neighbors) were mentioned by 5-20% of owners (Figure 4).

So what should we draw from this? Given that pet ownership is generally regarded as good for people, we should perhaps pause and remember that having a pet is not always necessarily straightforward. These results allow us to appreciate what an owner may be experiencing before, during and after a visit to the clinic. For example, the disconnect between a veterinarian feeling that their salary is too low and a pet owner perceiving that a visit to the practice is expensive is telling – and perhaps emphasizes the need for improved communication between the two parties.

Interestingly, the survey also identified some positive aspects that should give encouragement to the veterinary profession. 94% of owners trusted their veterinarian, and 92% expressed satisfaction with the service they received. Although some owners said that they found veterinarians to be overbearing, they regarded them as knowledgeable and did not believe that the status of the profession in today’s society was being weakened.

The way ahead

It is often remarked that undergraduates are taught a great deal of science in their veterinary course at college, but less about the other skills required to function effectively in practice. Despite the fact that veterinary practice involves treating animals, optimal interaction with the owners is essential for both animal welfare and to lessen the tensions felt by the clinician, and so the art of good communication should be regarded as a core part of any veterinary undergraduate syllabus. It would also seem appropriate for those of us in practice to regularly review our communication techniques and work hard to maintain and develop them. Basic business expertise and a fundamental understanding of how a practice is financed would also appear to be necessary skills for new graduates.

In addition, it would seem vital that professionals must be able to develop resilience to cope with the daily routine. We can use the topics highlighted by the survey as being most problematic for veterinarians (Figure 6) to select which ones we primarily identify with, and then design strategies to lessen their impact. It is imperative for our mental and physical well-being that we know how to de-stress if we find ourselves overwhelmed by the pressures of the job, and to be able to seek appropriate outside aid and support when necessary. Although the profession has made good progress in the support it can offer to its members, there is an indisputable need for these services to be promoted and developed further in the future. However, a passive approach is not enough – on an individual basis, we as clinicians should be actively working to take a positive view of our job, and develop a proactive approach to both our mental and physical health.

In particular veterinary students and new graduates should be made aware of the stresses that come with the job and encouraged to find ways to prevent development of pain points, rather than waiting for them to develop to a point where they impinge on a person’s workload and cause problems. But a holistic approach is necessary; an appreciation of the pain points that other stakeholders experience will allow the individual veterinarian to better understand some of the issues that can then develop into mutual mistrust, frustration or negative emotions.

We should be able to focus on the strengths of our job, and worry less about things we can have little influence over – for example, on-line sales of pet products are unlikely to be our staple source of income, and we should not spend too long trying to combat merchants who have the finances and resources to develop impressive websites. Similarly, we can counter on-line experts by offering sound clinical advice and excellent value for money to our clients, with a focus on playing to our strengths and emphasizing what we are good at. This will enable us to build bonds between the owner and the clinic, and will bolster the sustainability of both the individuals within a veterinary practice and the business itself.

Conclusion

Ultimately, if it is possible to reduce the pain points felt by veterinarians this will feed through to a better working environment, more contented individuals and better communication with other stakeholders, especially pet owners. It has been said that “the world we want tomorrow starts with how we do business today” and we need to remember the concept of the economics of mutuality – essentially if we understand each other better, we can benefit together. This should essentially lead to a better world for pets – a common goal shared by all involved in the companion animal sector worldwide.

The authors would like to thank Yassine El Ouarzazi of EoM Solutions for his advice and guidance in preparing this article.

Cara McNeill

University of Glasgow Veterinary College, Glasgow, UKUnited Kingdom

Cara McNeill worked in a variety of jobs to gain experience – including as an animal nursing assistant in a first opinion companion animal practice and on a sheep farm – for 15 months after completing her secondary school education before starting her studies at Glasgow Veterinary School, where she is now in her last year of study. With both her mother and father working as practitioners she has perhaps more insight than most students for what lies ahead once she qualifies.

Ewan McNeill

BVMS, CertVR, MRCVSUnited Kingdom

Dr. McNeill gained his veterinary degree from the University of Glasgow and spent five years in mixed practice before moving to focus on small animal matters. He is currently principal of a first opinion city centre practice, with a special interest in radiology and ophthalmology, but he also finds time to work as a consultant for a company that specializes in offering bespoke business advice to veterinarians. A long-time contributor to the professional press, he has served as editor in chief for Veterinary Focus since 2010.

Other articles in this issue

Share on social media