Minimally invasive bladder urolith removal

Minimally invasive options for removal of uroliths are now the standard of care in human medicine, and similar methods are finding increasing application in veterinary medicine, as Marilyn Dunn describes.

Key Points

Uroliths should always be removed from the urinary tract in the least invasive manner possible.

Struvite uroliths in cats and dogs can be dissolved within a short time period, and dissolution should be considered before more interventional techniques.

The minimally invasive technique chosen is tailored for an individual patient based on its size and gender, as well as the number and size of the stones.

Urolith analysis is essential in order to instigate proper preventative measures to reduce urolith recurrence.

Introduction

Lower urinary tract stones, not amenable to medical dissolution, can be removed through various minimally invasive methods. Stone removal is generally recommended as their continued presence can induce inflammation, obstruction or recurrent infection. Surgical removal of uroliths by cystotomy or urethrotomy has been the traditional method of choice, but both techniques have been associated with various complications – including urine leakage, wound dehiscence, bleeding, stricture formation and incomplete stone removal – reported in 20% of canine patients [1]. Additionally, suture material within the urethra or bladder wall may serve as a nidus for future urolith formation in stone-forming patients; analysis of recurrent lower urinary tract stones in patients that had undergone surgical cystotomy determined that 9.4% were suture-induced [2]. Recently, complications associated with traditional surgical cystotomy, regardless of closure method, were reported in 37-50% of cases, with a mean duration of hospitalization of 4 days [3].

In humans, minimally invasive treatment options have mostly replaced traditional surgical stone removal, as this is associated with a high recurrence rate of calculi, the need for serial surgeries that can lead to suture-induced stones, strictures, adhesions, bleeding, uroabdomen, pain and other life-threatening complications [4], [5]. The current standard of care for human urinary tract stones that cannot be passed or medically dissolved typically involves the use of minimally invasive methods.

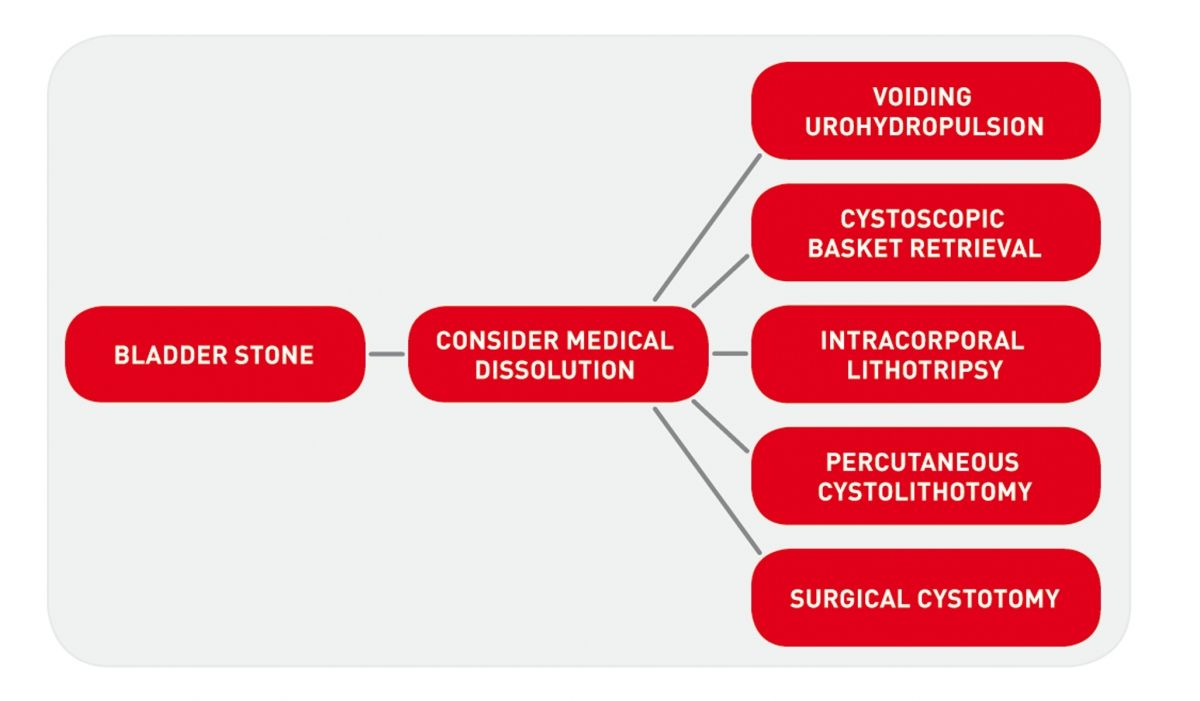

Such approaches have a multitude of advantages over standard surgery, including shorter hospitalization times, little to no recovery time and less discomfort. In small animals, minimally invasive treatment options for lower urinary tract stones consist of voiding urohydropropulsion (VUH), cystoscopic stone basket retrieval, intracorporeal lithotripsy and percutaneous cystolithotomy (PCCL) (Figure 1).

Minimally invasive removal options should be considered, discussed and offered to owners of pets suffering from uroliths [6]. While at times appearing technically simple, these procedures have been associated with serious complications when performed by inadequately trained personnel, and referral to a formally trained and experienced specialist is indicated.

This article will review the current minimally invasive treatment options for bladder and urethral urolith removal. All the procedures described below should be performed in a sterile manner, with patients clipped and aseptically prepared, and all instruments which will enter the urinary tract must be sterile.

Bladder and urethral urolithiasis

Various interventional approaches may be considered for removal of lower urinary tract uroliths, depending on the species, sex, type of stone present and stone burden, and consideration of a minimally invasive approach to stone removal in lieu of surgical cystotomy is to be recommended in most cases. Correct assessment of stone size is critical in selecting the most appropriate intervention. Uroliths should be measured by standard radiography (or contrast radiography for radiolucent stones) using a radiopaque marker, rather than by ultrasound, which tends to overestimate urolith size and underestimate the number of uroliths [6].

Voiding urohydropropulsion

Indications

This method (Box 1) allows antegrade removal of bladder stones through the urethra. It is recommended for small stones < 3-4 mm diameter in female dogs, < 2.5 mm in female cats, but is limited by the size of the penile urethra in male dogs. Voiding urohydropulsion should not be attempted in male cats, as there is a high risk of urethral obstruction [7].

| Size and number of uroliths | Stones < 3-4 mm in small female dogs Stones < 2.5 mm in female cats Male dogs limited by size of penile urethra |

| Sex and species | Female dogs and cats Not indicated in male cats as risk of urethral obstruction |

| Advantages | Quick Low-cost equipment Quick Can be done in general practice |

| Disadvantages | Stones may remain in the bladder Large and spiculated stones may obstruct the urethra |

Equipment

An appropriately sized urinary catheter, syringe, and saline.

Intervention

Under general anesthesia, a urinary catheter is used to fill the bladder with saline. It is important to avoid overfilling; the estimated bladder capacity is 10-15 mL/kg. If a urinary catheter cannot be passed in a female dog or cat, the catheter can be inserted into the vestibule and the vulva gently closed with digital pressure; filling of the vestibule with saline will result in passive filling of the vagina, urethra and bladder. The bladder should be palpated during filling to avoid over-distension, and filling should be stopped when it feels firm. The urinary catheter is then removed; in females, the patient is then positioned vertically, males are placed in lateral recumbency. The urinary bladder is palpated, shaken gently and pulled cranially to straighten the urethra. Gentle but steady pressure is applied to the urinary bladder to induce micturition. The procedure is repeated until all stones have been retrieved (Figure 2a) (Figure 2b).

Complications

This procedure is generally well tolerated, but mild hematuria may be noted. Careful palpation of the urinary bladder while filling with saline is recommended in order to prevent overfilling and bladder rupture. Inadvertent urethral obstruction due to numerous uroliths being voided may occur while performing the procedure.

Alternatives

Other options are cystoscopic stone basket retrieval, lithotripsy, percutaneous cystolithotomy or cystotomy.

Cystoscopic-guided basket retrieval

Indications

This technique (Box 2) is suitable for removal of urethral and bladder stones not amenable to medical dissolution and too large to be evacuated by voiding urohydropulsion. Basket retrieval can be considered in female dogs with stones < 5 mm diameter, male dogs with stones < 4 mm (limited by the size of the os penis), and female cats with stones < 3-4 mm [8] [9]. The small diameter of the male cat’s urethra prevents cystoscopy with a working channel.

| Size and number of uroliths | Stones < 5 mm in small female dogs Stones < 3-4 mm female cats Male dogs limited by size of penile urethra (2-3 mm) |

| Sex and species | Female dogs and cats Male dogs > 7 kg (penile urethra must allow passage of the flexible scope) |

| Advantages | Quick No suture material in the bladder |

| Disadvantages | Specialized equipment |

Equipment

This requires a rigid or flexible cystoscope, and a stone basket that can be passed through the working channel of the cystoscope.

Procedure

The patient is anesthetized and placed in dorsal (female) or lateral (male) recumbency. An epidural anesthetic may enhance lower urinary tract relaxation and facilitate stone retrieval. Cystoscopy is used to visualize the urolith(s) and a stone basket is passed through the working channel of the scope to grasp the stone. Under continuous saline flush, the basket is pulled towards the tip of the scope and both scope and basket are then withdrawn. If resistance is felt, the flush pressure can be increased in order to help dilate the urethral lumen and the basket can be gently rotated. If resistance is still felt, the basket should be opened to release the stone and another technique used in order to avoid damage to or perforation of the urethra (Figure 3a) (Figure 3b).

Special considerations

In the presence of urethral stricture/inflammation, the clinician should be prepared to remove the stone using another technique.

Complications

Urethral stricture or perforation is possible during retrieval of embedded or sharp-edged stones.

Alternatives

Lithotripsy, percutaneous cystolithotomy or cystotomy may be considered.

Before deciding on the preferred method for stone removal, radiography should be used to measure the size of the uroliths; ultrasound tends to overestimate urolith size and underestimate the number of uroliths.

Intracorporal lithotripsy

Indications

This technique (Box 3) may be used for removal of urethral and bladder stones not amenable to medical dissolution and that are too large to be removed by cystoscopic-guided basket retrieval [10] [11] [12] [13].

| Size and number of uroliths | Low stone burden preferable |

| Sex and species | Female cats and dogs Male dogs > 7 kg |

| Advantages | No suture material in the bladder |

| Disadvantages | Specialized equipment Long procedural length with large stone burden |

Equipment

A Hol:Yttrium Aluminium Garnet (Ho:YAG) low power surgical laser with a laser fiber that can be passed through the scope channel, or an electrohydraulic lithotripter; a rigid or flexible cystoscope, and (optionally) a stone basket.

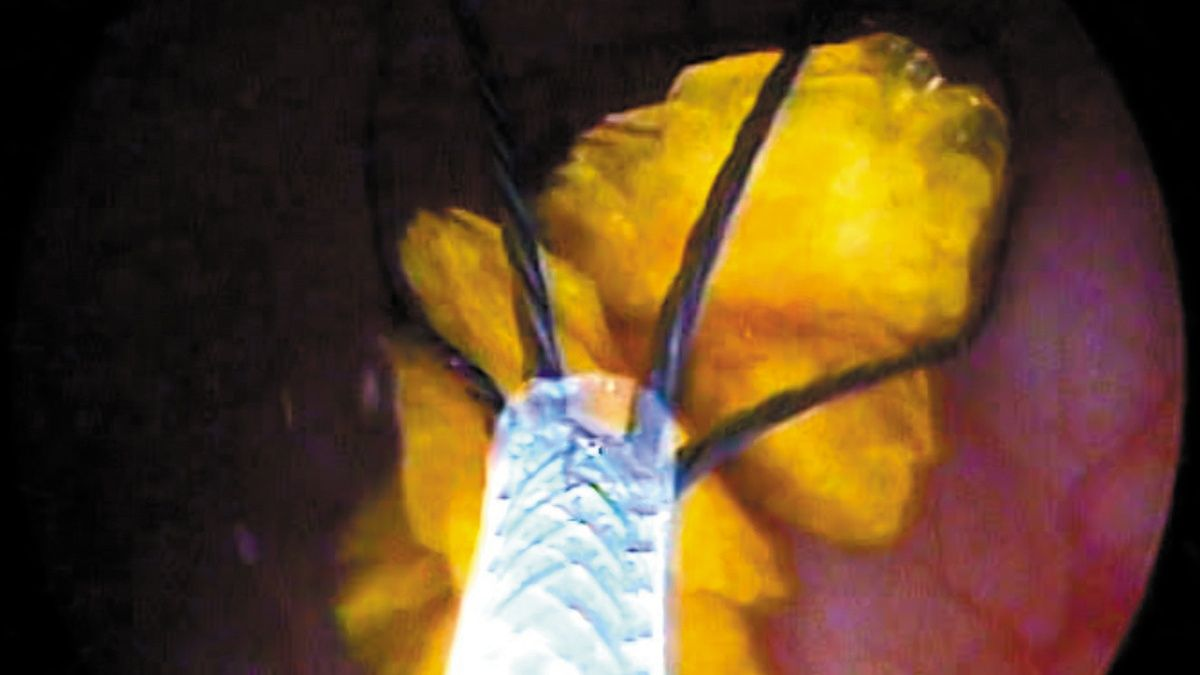

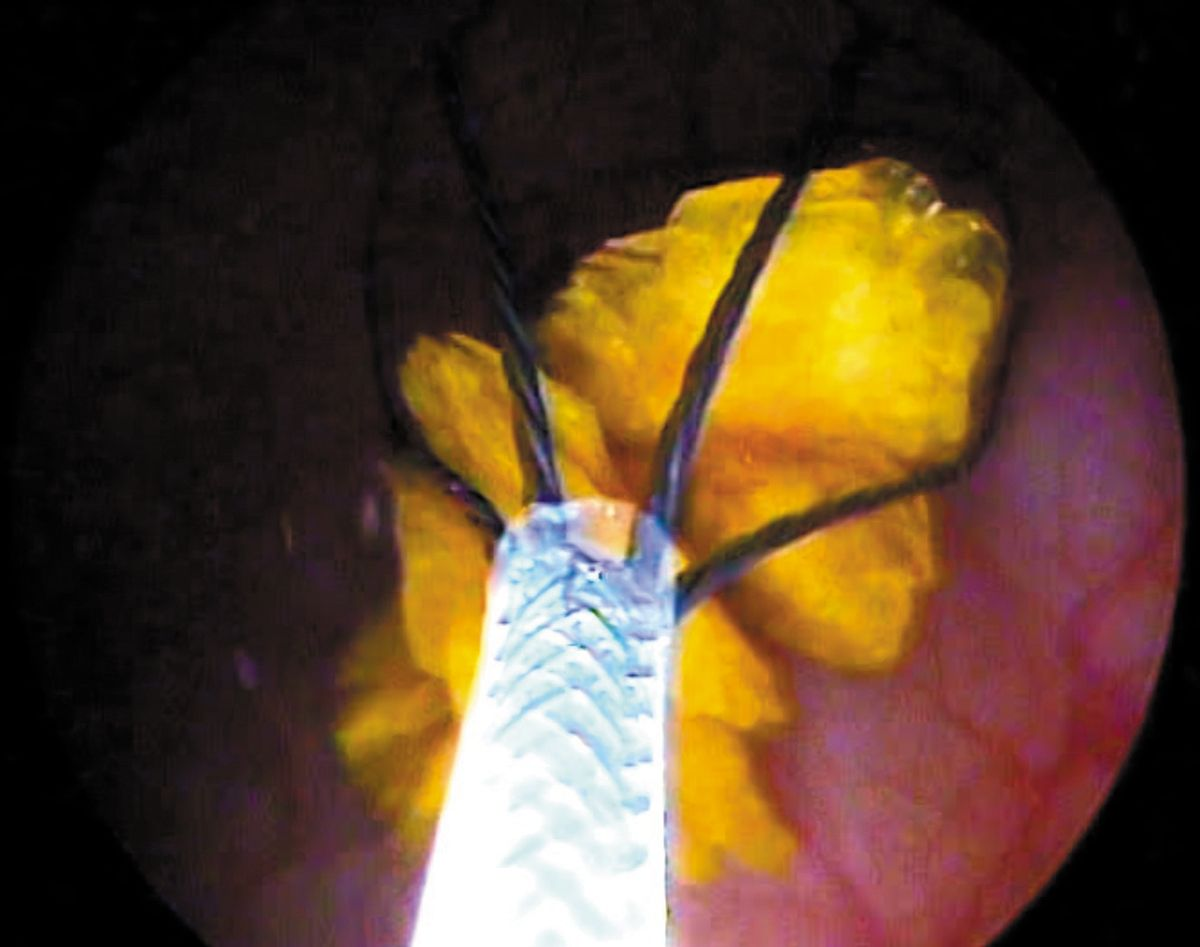

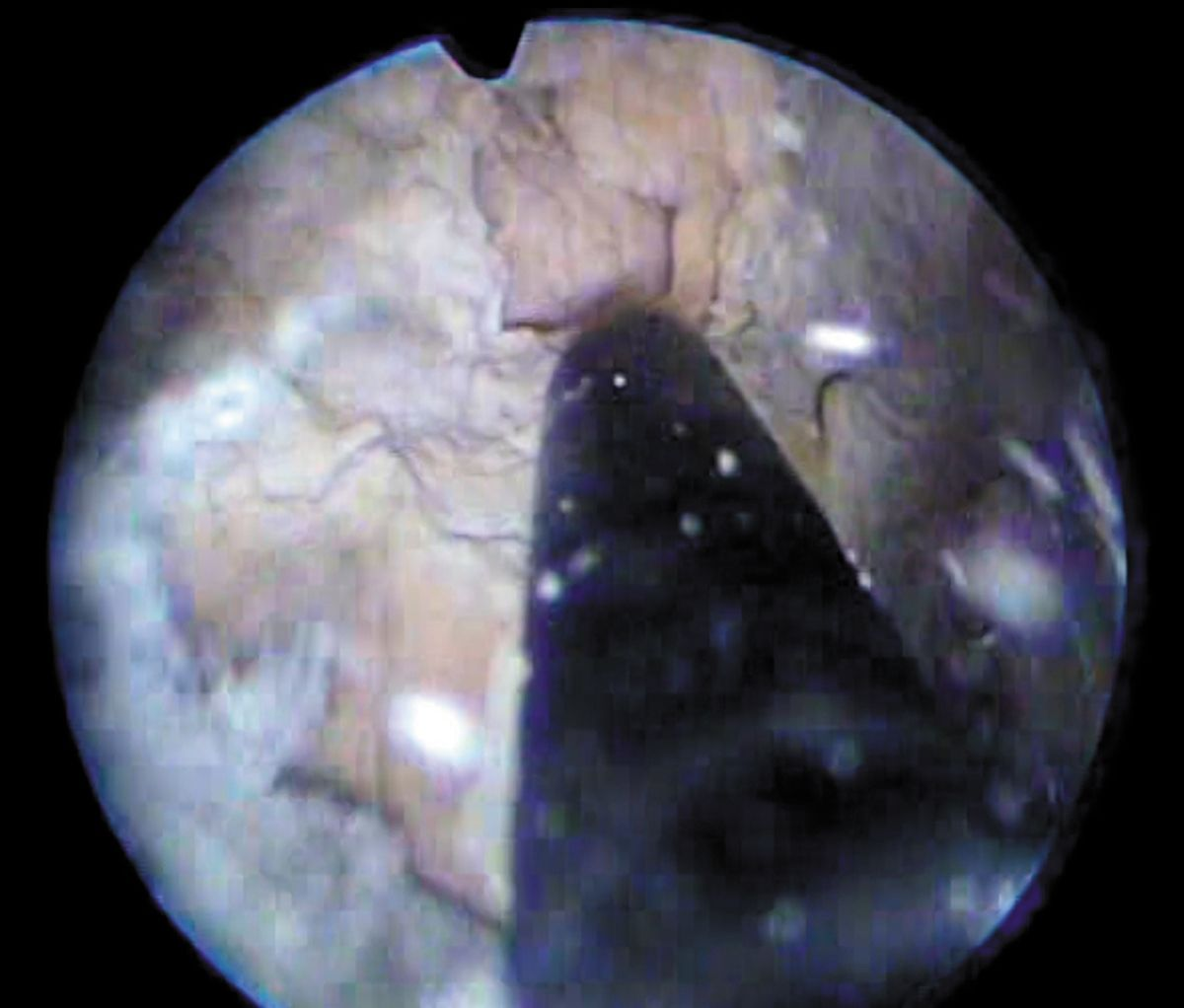

Procedure

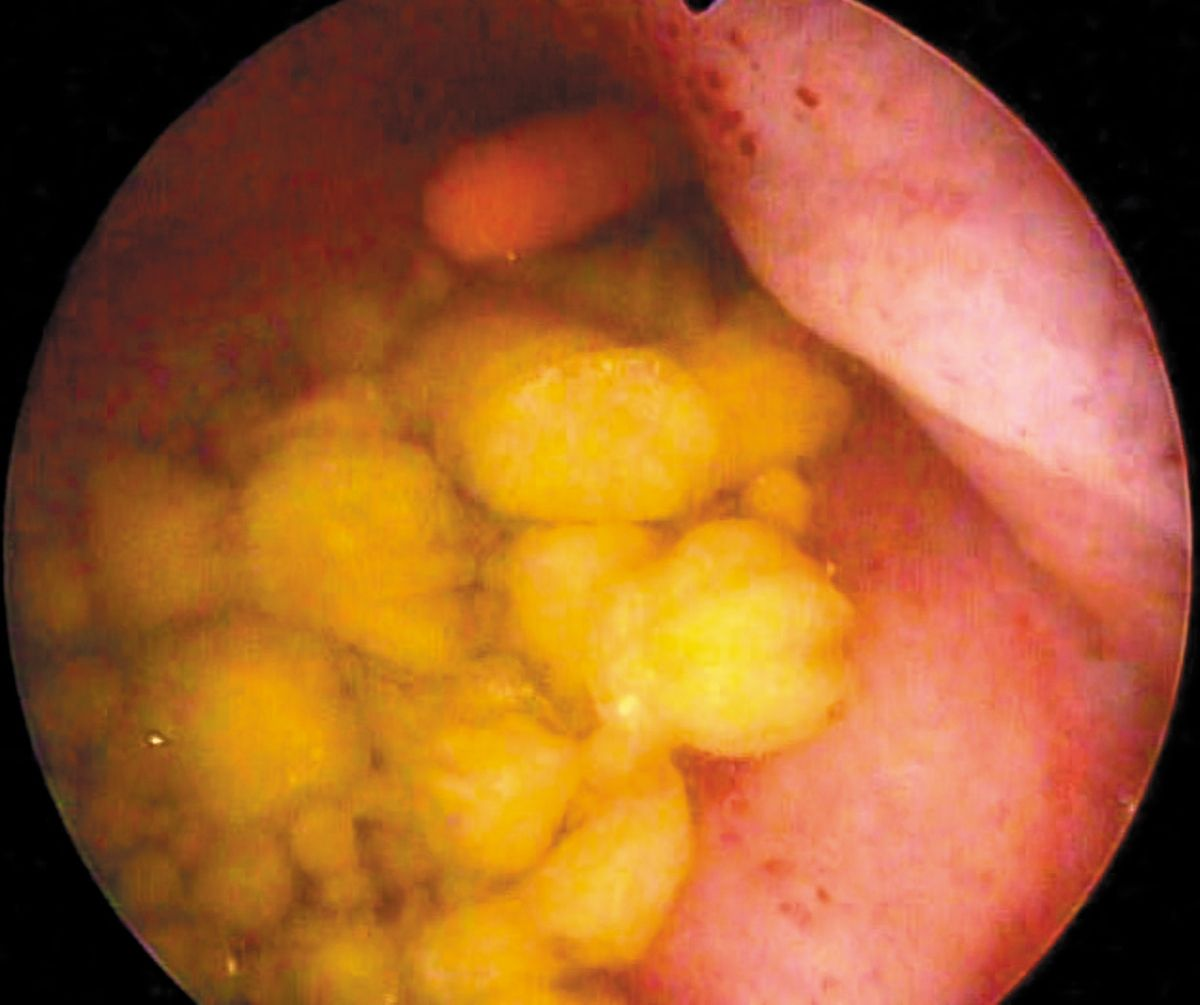

The patient is anesthetized and placed in dorsal (female) or lateral (male) recumbency. Cystoscopy is used to visualize the stone. If an electrohydraulic lithotripsy is used, the tip of the fiber is placed in direct contact with the surface of the urolith at an angle of 90°. The stone is fragmented by the lithotriptor’s energy transmitted directly to the stone, creating a shock wave that induces fragmentation.

With the Ho:YAG laser, pulsed laser energy is transmitted from the energized crystal to the urolith via the fiber. The stone is fragmented by a thermal drilling process, in which the pulse energy traveling through the fiber creates a microscopic vapor bubble on the surface of the calculus. This microscopic “parting” of the fluid medium by an air bubble (known as the Moses effect) allows the laser’s energy to be transmitted directly into the stone, creating a shock wave that induces stone fragmentation.

If the fiber tip is 1 mm or more away from the stone, the vapor bubble collapses, the water or saline absorbs the energy, and no energy is transmitted to the urolith. As the fiber tip is advanced to within 0.5 mm of the calculus, the vapor bubble comes in contact with the stone. The closer the fiber tip is to the target, the larger the effect, with the greatest effect achieved when the fiber is in direct contact with the stone. The energy is absorbed in < 0.5 mm of fluid, making it safe to fragment uroliths in tight locations, such as within the urethra, ureter, renal pelvis, or urinary bladder, with limited risk of adjacent urothelial damage [14].

Stones are fragmented until the pieces are small enough to be voided using urohydropulsion or removed with a stone retrieval basket (Figure 4a) (Figure 4b) (Figure 4c) (Figure 4d). One study reported the use of a basket to move smaller bladder stones into the urethra before fragmentation to minimize their movement during lithotripsy, with the technique resulting in more complete fragment removal [11].

Special considerations

The major challenge with this method is removal of stone fragments from the urinary tract, especially in male dogs. Its success depends on careful patient selection. A large number of large stones in a small patient are best removed by PCCL.

Outcome

The Ho:YAG laser is effective on all stone types [14]. Complete urolith removal is achieved in 100% of dogs with urethroliths, 83-96% of female dogs with cystoliths, and 68-81% of male dogs with cystoliths [10,] [11,] [12,] [13].

Complications

Urethral edema, which is self-limiting, and mild hematuria may be seen. Bladder perforation by the laser is a rare occurrence, and can be treated by leaving a urinary catheter in place for 24-48 hours [10], [11,] [12,] [13].

Alternatives

Percutaneous cystolithotomy, surgical cystotomy and/or urethrotomy.

Percutaneous cystolithotomy (PCCL)

Indications

PCCL (Box 4) can be used for removal of urethral and bladder stones that are not amenable to medical dissolution and are too large or too numerous to be removed by voiding urohydropulsion, cystoscopic-guided basket retrieval or lithotripsy. The approach, which is through the bladder apex, can also be used to gain access to the urethra, bladder and ureters [16].

| Size and number of uroliths | No restrictions |

| Sex and species | No restrictions |

| Advantages | Excellent visualization of the entire lower urinary tract and easy retrograde stone removal |

| Disadvantages | Specialized equipment Access to lithotripsy may be necessary for large or embedded stones |

Equipment

A urinary catheter, standard surgical instruments, laparoscopic threaded cannula (trochar) with diaphragm, rigid and flexible cystoscopes, stone basket, lithotripsy (required for embedded stones).

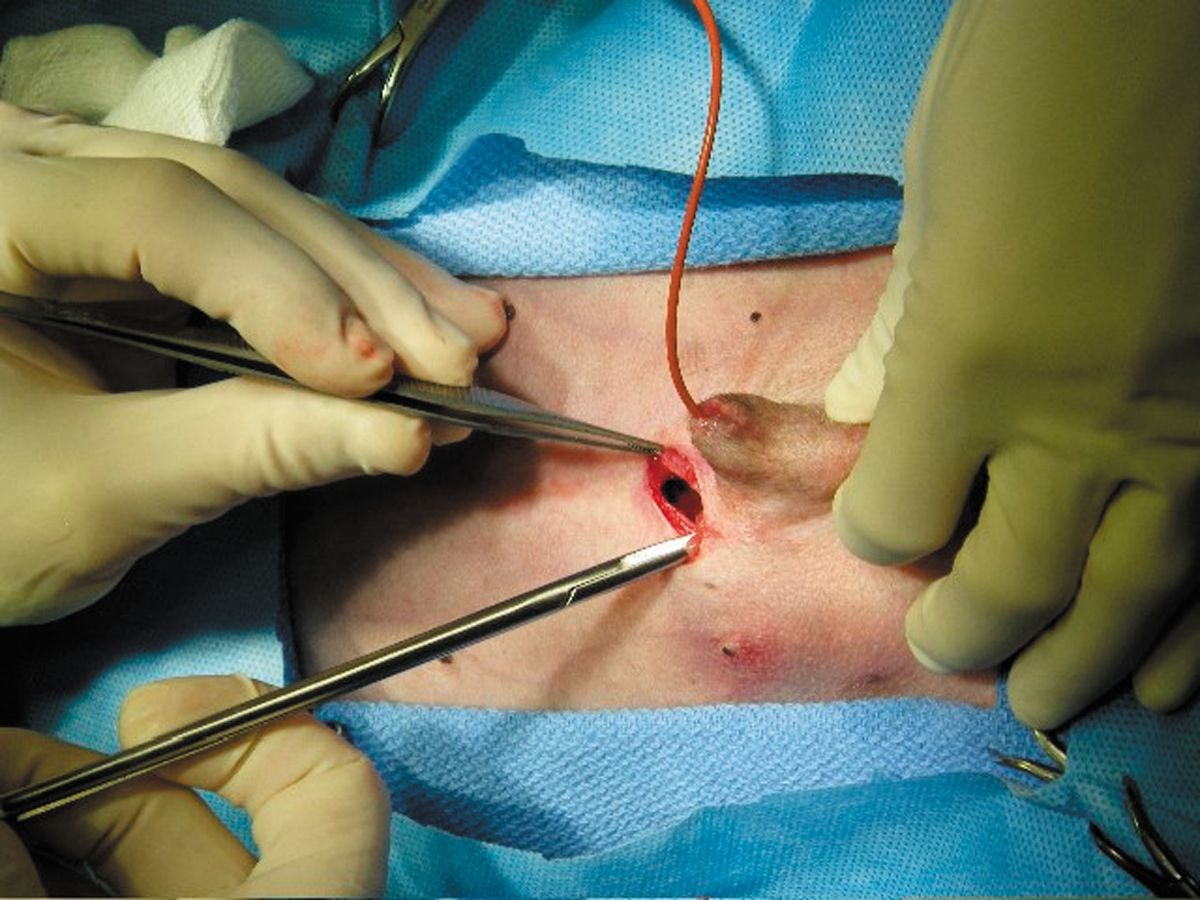

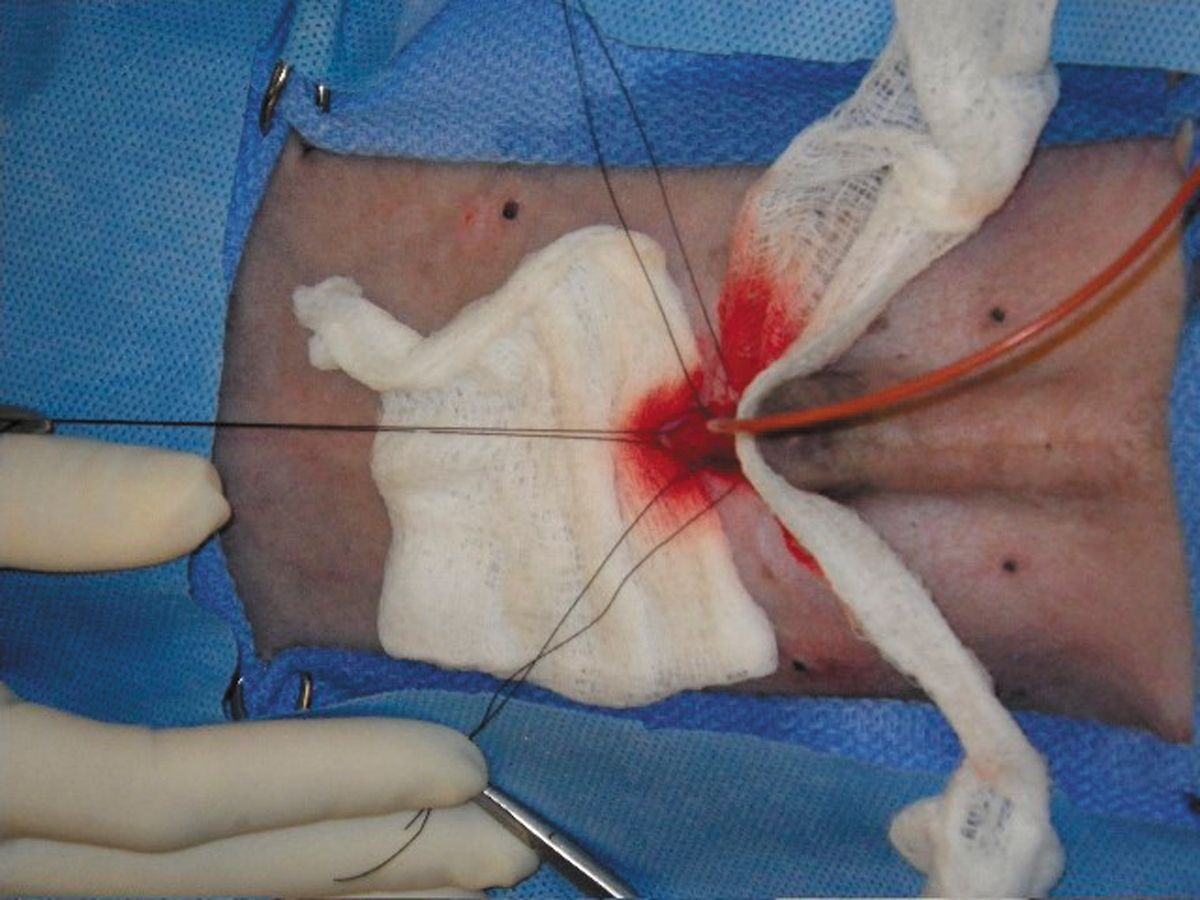

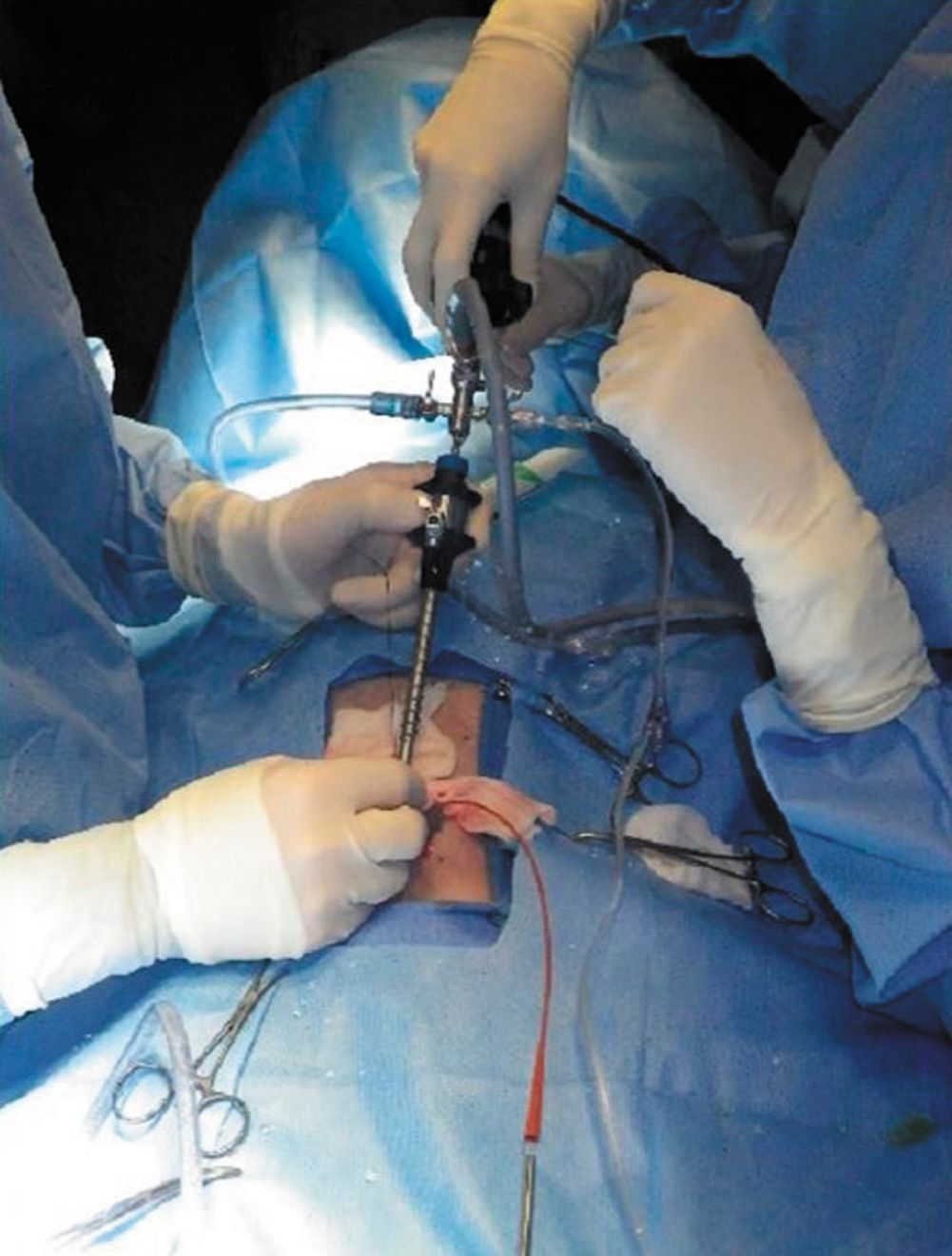

Procedure

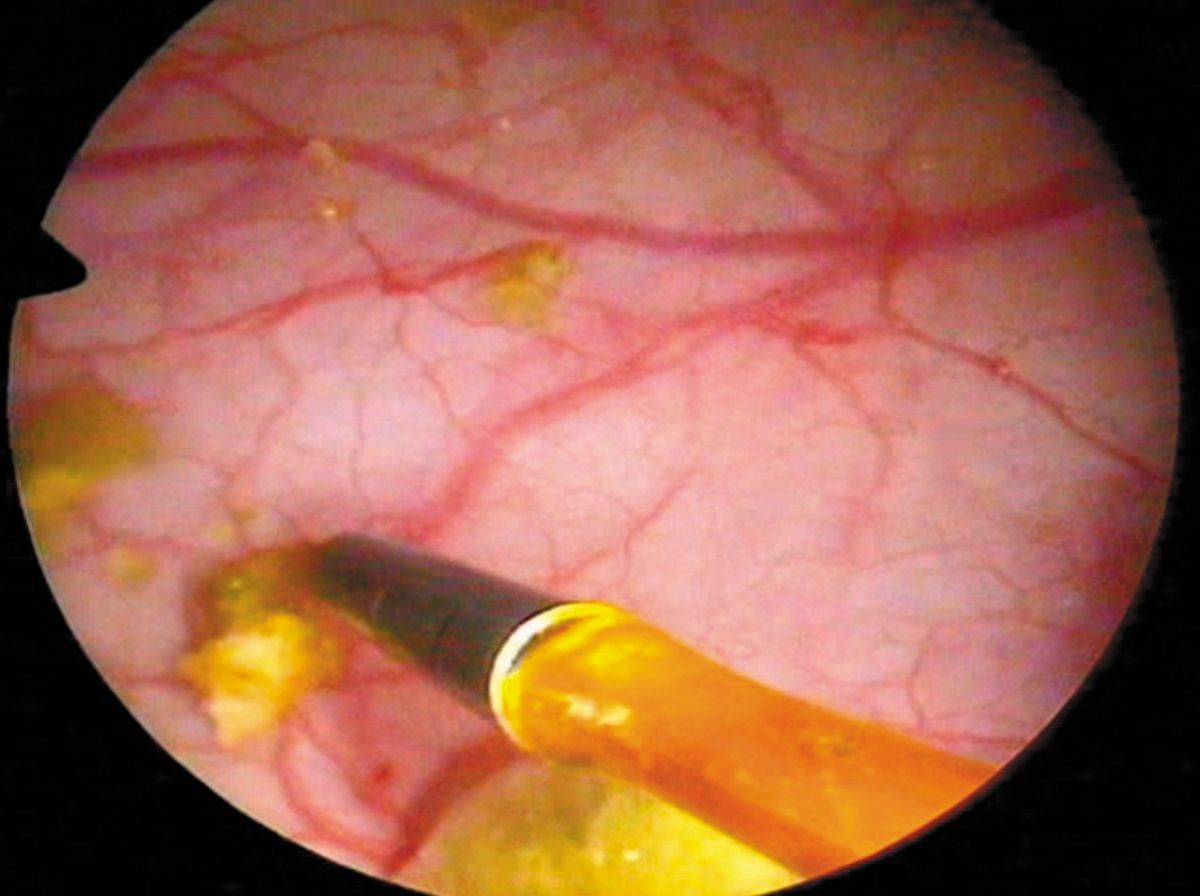

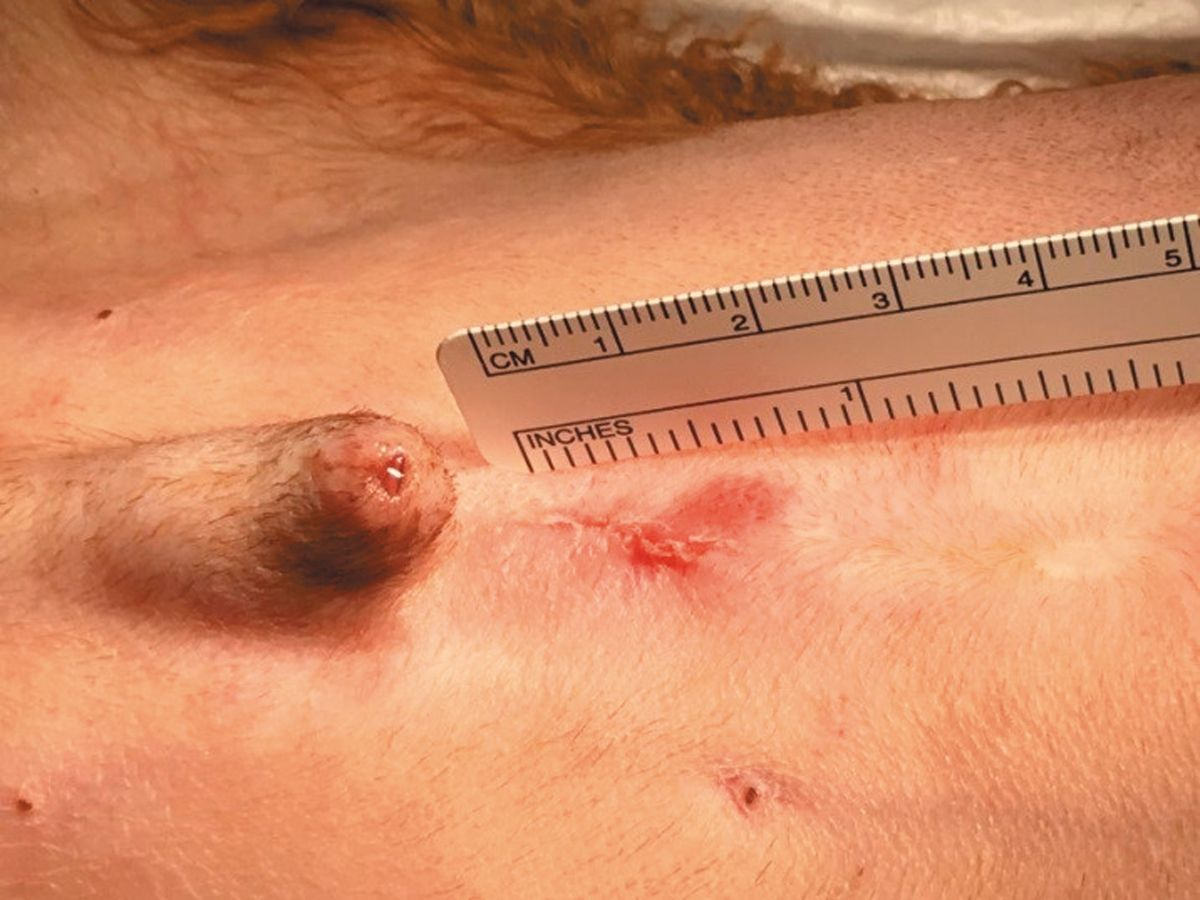

The patient is anesthetized and placed in dorsal recumbency. A urinary catheter is placed and sterile saline infused until the bladder apex is palpable. A 1-2 cm ventral midline skin incision is made over the area of the bladder apex into the abdominal cavity. The bladder apex is identified and tissue forceps are used to grasp the apex. Stay sutures are placed and a stab incision is made at the bladder apex. The laparoscopic cannula is screwed in place and directed toward the urethral lumen. A rigid cystoscope is advanced through the cannula into the bladder and the stones are identified and removed with the stone basket. Once all bladder stones are removed, the urethra is examined (using a flexible scope in male dogs and a rigid scope in female dogs and cats). Stones in the urethra can be removed with a stone basket or flushed into the bladder and removed. The cannula is withdrawn and the bladder incision and abdomen closed (Figure 5a) (Figure 5b) (Figure 5c) (Figure 5d) (Figure 5e) (Figure 5f) (Figure 5g) [16].

Outcome

Complete stone removal is achieved in 96% of patients [16].

Complications

Wound infection, dehiscence and uroabdomen are rare potential complications associated with the transabdominal approach.

Other considerations

Stone recurrence is a concern. Laser lithotripsy is occasionally required as larger cystoliths may otherwise need to be removed by stretching/extending the bladder incision. This procedure can be performed on an outpatient basis, but if a patient has a urinary tract infection, antibiotic therapy should be administered prior to the procedure due to the increased risk of septic peritonitis.

Alternatives

Surgical cystotomy and or urethrotomy may be considered.

Minimally invasive stone removal is the new standard of care in small animal veterinary medicine. In comparison with standard surgical procedures, the techniques are associated with minimal tissue injury, shorter hospitalizations, smoother recovery and decreased peri-operative morbidity and mortality. A thorough understanding of the therapeutic options available is essential to properly educate and inform the client. Proper equipment, technical expertise and experience are essential prerequisites to many of these procedures. Once stones have been removed and analyzed, developing a proper prevention regime is essential to minimize stone recurrence.

References

- Grant DC, Harper TA, Werre SR. Frequency of incomplete urolith removal, complications, and diagnostic imaging following cystotomy for removal of uroliths from the lower urinary tract in dogs: 128 cases (1994-2006). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2010;236:763-766.

- Appel SL, Lefebvre SL, Houston DM, et al. Evaluation of risk factors associated with suture-nidus cystoliths in dogs and cats: 176 cases (1999-2006). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008;233:1889-1895.

- Thieman-Mankin KM, Ellison GW, Jeyapaul CJ, et al. Comparison of short-term complication rates between dogs and cats undergoing appositional single-layer or inverting double-layer cystotomy closure: 144 cases (1993-2010). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2012;240:65-68.

- Urena R, Mendez-Torres F, Thomas R. Complications of urinary stone surgery. In: Stoller ML, Meng MV (eds.) Urinary Stone Disease: The Practical Guide to Medical and Surgical Management. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc; 2007:511-553.

- Carlin BI, Paik M, Bodner DR, et al. Complications of urologic surgery prevention and management. In: Taneja SS, Smith RB, Ehrlich RM (eds.) Complications of Urologic Surgery 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2001:333-341.

- Lulich JP, Berent AC, Adams JL, et al. ACVIM Small Animal Consensus Recommendations on the Treatment and Prevention of Uroliths in Dogs and Cats. J Vet Intern Med 2016;30;1564-1574.

- Lulich JP, Osborne CA, Carlson M. Nonsurgical removal of uroliths in dogs and cats by voiding urohydropropulsion. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1993;203;660-663.

- Defarges A, Dunn M, Berent A. New alternatives for minimally invasive removal of uroliths: lower urinary tract uroliths. Comp Cont Educ Small Anim Vet 2013;35(1):E1-7.

- Berent A. New techniques on the horizon: Interventional radiology and interventional endoscopy of the urinary tract (“endourology”). J Feline Med Surg 2014;16(1):51-65.

- Defarges A, Dunn M. Use of electrohydraulic lithotripsy to treat bladder and urethral calculi in 28 dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2008;22:1267-1273.

- Adams LG, Berent AC, Moore GE, et al. Use of laser lithotripsy for fragmentation of uroliths in dogs: 73 cases (2005-2006). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008;232:1680-1687.

- Grant DC, Werre SR, Gevedon ML. Holmium:YAG laser lithotripsy for urolithiasis in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2008;22:534-539.

- Lulich JP, Osborne CA, Albasan H, et al. Efficacy and safety of laser lithotripsy in fragmentation of urocystoliths and urethroliths for removal in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2009;234(10):1279-1285.

- Lulich JP, Adams LG, Grant D, et al. Changing paradigms in the treatment of uroliths by lithotripsy. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2009;39:143-160.

- Wynn VM, Davidson EB, Higbee RG, et al. In vitro effects of pulsed holmium laser energy on canine uroliths and porcine cadaveric urethra. Lasers Surg Med 2003;33:243-246.

- Runge JJ, Berent AC, Mayhew PD, et al. Transvesicular percutaneous cystolithotomy for the retrieval of cystic and urethral calculi in dogs and cats: 27 cases (2006-2008). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2011;239 (3):344-349.

Marilyn Dunn

DMV, MVSc, Dipl. ACVIMCanada

Marilyn Dunn is currently a professor in internal medicine and heads the interventional medicine service at the University of Montreal. A graduate of the University, she was board certified by the ACVIM in 1999 and is a founding member (and current president) of the Veterinary Interventional Radiology and Interventional Endoscopy Society (VIRIES). Her main interests are in urinary tract and respiratory interventions, and thrombosis

management. She has published many scientific articles and book chapters, and lectures widely on interventional medicine.

Other articles in this issue

Share on social media