Veterinary forensics

Written by Nienke Endenburg

Animal abuse is an overlooked area of the undergraduate veterinary curriculum, and clinicians need to be more aware of the potential for animal abuse in their daily consultations, as Nienke Endenburg describes.

Veterinarians play a hugely important role in the investigation and prosecution of animal abuse cases.

Non-accidental injury (NAI) and animal abuse, domestic violence and child abuse are all interlinked.

Detection of NAI requires recognition of a combination of signs and signals from both the owner and the animal.

When faced with a possible NAI case the veterinarian must work with other professionals, including forensic experts and the police, to identify the problem.

Introduction

“When animals are abused, people are at risk; when people are abused, animals are at risk.” This quote from Phil Arkow, an internationally recognized campaigner for human-animal interactions and violence prevention, is as good an introduction as any to the subject of animal abuse and what it means to society. Animal abuse can be defined as “an intentional act that causes harm to an individual” and is a worldwide problem, causing an incalculable degree of animal suffering [1]. However, despite the vast amount of suffering involved, animal abuse has so far received scant attention as a research subject [2]. Social media will frequently carry messages regarding real and potential animal abuse, but the actual incidence of abuse remains unclear. There are various reasons for this, including the fact that veterinarians can find it difficult to recognize animal abuse, and if they do suspect it, they hesitate to report it to the authorities in case it is not; they do not wish to falsely accuse someone. Therefore animal abuse is greatly under-reported [3]

Animals will often act as indicators of human health and welfare, as can be seen in the link between animal abuse, family and social violence [4] [5]. There is significant evidence to demonstrate that those who mistreat and abuse animals can and do show the same behavior towards vulnerable people around them, such as children or the elderly. It is also often the case that those convicted of murder have a history of animal abuse [6]. If veterinarians are able to identify animal abuse then it can be a starting point to see if there is also domestic violence or child abuse within a family.

In this article non-accidental injuries (NAI), a synonym for physical abuse [7] will be highlighted, although neglect and sexual abuse also come within the definition of animal abuse. NAI is deliberate and can take various forms, including hitting, shaking, throwing, poisoning, burning, scalding, suffocation, and asphyxiation. The clinical presentations may include injuries to the skeleton, soft tissues or organs sustained as a result of beating or repeated maltreatment (Figure 1)[8].

The veterinary mindset

Sometimes the signs of animal abuse are obvious, but they are often overlooked by veterinarians who are usually caring individuals that find it difficult in the first place to accept that people maltreat animals; veterinarians will also often not realize that separate incidents or injuries are linked to abuse. In addition animals may have no external signs of physical damage, but can have many internal injuries, fractures and hemorrhage. It is also often thought that animals that are abused are not presented to a veterinary clinic, but this is untrue; abused animals are as likely to be taken to a veterinarian as animals that are not abused [9]. In most cases it is not the abuser who brings the animal to the practice, but rather someone else, e.g., the partner of the abuser or another family member. In addition, animals that are abused will very often be taken to more than one veterinary practice, and in most cases the veterinarian will be unaware that that they are not the only one who is treating that animal. Alternatively, if an animal is seen by multiple vets within a practice, the abuse may not be immediately recognized. Medical colleagues – including doctors, dentists and other healthcare professionals – also face the same dilemma, and acknowledge that the biggest challenge to recognizing the problem and actually diagnosing abuse is the powerful emotional block in the mind of the professional. They must force themselves to think about abuse in the first place; only by recognizing the problem can the veterinary profession become a part of the link to break the cycle of violence (Figure 2) [10]. In fact, NAI should be included in the differential diagnosis list for many cases seen in the clinic [8].

How can NAI be recognized?

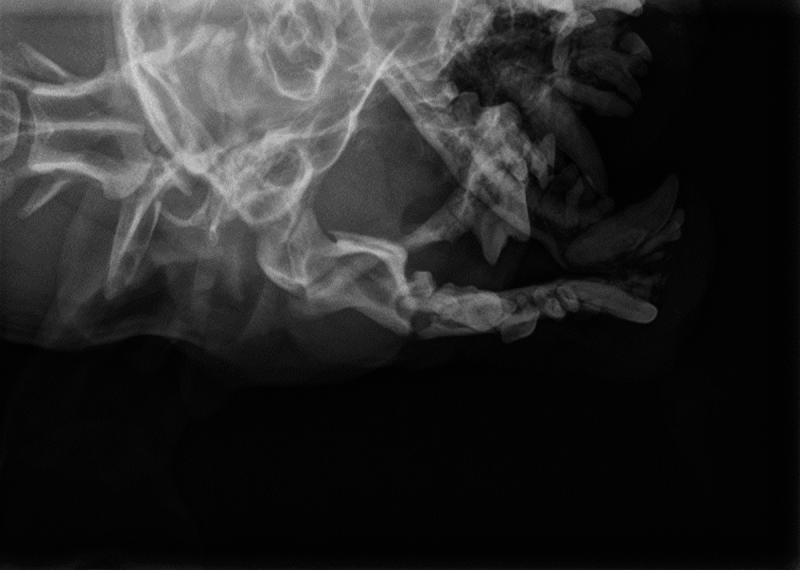

Recognizing NAI can only be done by combining signs from both the animal and the owner, as set out in Table 1 and Table 2. For instance, the owner’s behavior may be suspicious. As an example, the history can vary when asked for the cause of the trauma; the owner may initially state that another dog sat on the injured animal, but at the second consult will say that it was an accident with a bike. Sometimes there can be a reluctance to come to follow-up consultations. Certain categories of injuries should raise the suspicion of NAI. The presenting history may not correlate with the clinical findings, especially if the story sounds implausible. For example the owner of an injured dog may suggest that their pet is clumsy and was hurt by tumbling down the stairs, or that the animal’s fractured limbs are the result of falling off a wall, or that a head injury was due to the dog walking into a door. An automobile accident is often cited as the cause of abuse injuries, but if radiography reveals fractured bones at different stages of healing this should raise a red flag for possible animal abuse; this sort of injury will not be caused by a single accident (Figure 3).

When the treating veterinarian has reasonable grounds to suspect animal abuse, it may be helpful to consult a colleague, but it is also essential for veterinarians to work with other professionals – such as the police and forensic experts – who can contribute their knowledge and expertise.

|

|

|

Animals at risk

Abuse can happen to any animal, but there are certain categories that are at greater risk. These include dogs and cats below the age of two, animals that require more care than usual, (e.g., very young or very old animals), and animals that are noisy or that have behavior problems (Figure 4) [11]. Research also shows that ‘dangerous dogs’ have a higher risk of being abused because they are significantly more likely to have owners who have a criminal history and/or an antisocial personality disorder [12]. One study found that in 21% of cases where dog bites resulted in the death of a person, it involved dogs that had been abused [13].

Motives for animal abuse and domestic violence

Studies have shown that people who abuse animals can have had negative experiences in childhood; for example, they have been the victim of and/or have seen interpersonal violence and/or animal abuse. These children are three times more likely to abuse animals than children who have not had similar experiences [14] [15].

|

People can have many different motives for abusing animals, including curiosity, excitement, teasing, or a desire to hurt [16] [17]. Animal abuse may also be used to control, intimidate or blackmail others, or to isolate or manipulate someone. A desire to punish, shock, or take revenge on a person, or to emphasis prejudices, can also be a significant factor, or there may be a sadistic motive [18]. In almost half of the cases the reason for committing the abuse is aggression, and in a third of the cases it is pleasure [19], and feelings of humiliation and fear can also play a part [20]. Table 3 lists some of the commonest motives. Power and control will mainly be involved when animal abuse takes place in the context of interpersonal violence [21]; 70% of people who abuse animals have also committed other violent crimes [22].

Animals often act as indicators of human health and welfare, as can be seen in the link between animal abuse, family, and social violence. There is significant evidence that people who mistreat and abuse animals show the same behavior toward vulnerable people around them, such as children or older adults [23]. Animals can also be used to force women and children to stay in an abusive situation, because otherwise there may be the threat that the animal will be killed [10]. Women will therefore sometimes stay too long in an abusive situation because there is no safe shelter where they, their children and their animals can go to seek protection. Fortunately, there are now more and more places which will offer shelter to animals as well as protection for women and children when this situation arises.

What to do if abuse is suspected

Every practice should have a practice protocol for animal abuse, so that all members of the veterinary team know what to do. Veterinarians play a critical role in the investigation and prosecution of animal abuse cases [25]. It is often thought, however, that veterinarians should both recognize the abuse and identify the perpetrator, but this is not correct. Veterinarians can conduct physical examinations, collect evidence at the scene, run laboratory tests and perform necropsies that may provide vital evidence [25] if there is a suspicion of animal abuse, but after this point a designated legal body (e.g., the police) should take over. It is then up to the judicial system to find out who has abused the animal and to punish the perpetrator [2] [8]. With any suspected case, the clinician should record all the relevant information in the patient’s clinical records, along with as much evidence as possible, such as radiographs and photographs of the animal's injuries. The question as to the confidentiality of these records, and whether information can be reported to other family members, other practitioners, or animal welfare or law enforcement authorities, has become a contentious issue nowadays, and differs widely between countries. It is mandatory to report animal abuse in some countries, whilst in others there is a recommended reporting code to help veterinarians take the appropriate steps. Veterinarians should be knowledgeable about the legal situation in their own country or state.

The signs of animal abuse can be obvious but are often overlooked by veterinarians, who find it difficult to accept that people can maltreat animals, or do not realize that separate traumatic incidents can be linked to an abusive owner.

The Veterinary Forensic Expert Centre

In the Netherlands the Veterinary Forensic Expert Centre (Landelijk Expertisecentrum Dierenmishandeling, or LED) was set up in 2017 with several goals. The first objective is to help practicing veterinarians who believe that they may have a case of animal abuse in their practice. The veterinarian can upload radiographs, pictures, videos and written information regarding an animal onto the LED website. An expert panel of specialized veterinarians, along with forensic experts from the Dutch Forensic Institute (NFI, based in The Hague), will assess the material and inform the veterinarian within 48 hours if this could be a potential animal abuse case or not. If it is, the veterinarian can pass the information to the police, who will then undertake further inquiries. A second goal of the LED is to undertake scientific research on veterinary forensics, such as forensic radiology. The third aim is to educate veterinarians, human doctors, psychologists, social workers and the general public about animal abuse and how it relates to domestic violence.

Veterinarians, together with other health professionals, play a crucial role in the prevention and discovery of animal abuse and domestic violence. All clinicians must be alert to the possibility of NAI during their daily consultations, and should have a protocol that can be followed if a case is suspected. Increased education and better awareness in this area, along with improved co-operation with other professions, can help address this problem and assist a reduction in unnecessary suffering for both animals and humans.

Nienke Endenburg

PhDNetherlands

A clinical psychologist, Dr. Endenburg gained her PhD from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in Utrecht and has worked there since 1987, focusing on the human-animal bond. Her main interest is in animal-assisted interventions and animal abuse and domestic violence. She is currently the coordinator of the Veterinary Forensic Expert Centre, which is based at Utrecht University.

References

- McMillan FD, Duffy DL, Zawistowski SL, et al. Behavioral and psychological characteristics of canine victims of abuse. J App Animal Welfare Sci 2015;18:92-111.

- Links Group. Recognizing abuse in animals and humans: Guidance for veterinary surgeons and other veterinary employees. Milton Keynes, UK: The Links Group 2013;4.

- Yoffe-Sharp BL, Loar LM. The veterinarian’s responsibility to recognize and report animal abuse. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2009;234(6):732-737.

- Ragatz L, Fremouw W, Thomas T, et al. Vicious dogs: the antisocial behaviors and psychological characteristics of owners. J Forensic Sci 2009;54(3):699-703.

- Patronek GJ, Sacks JF, Delise KM, et al. Co-occurrence of potentially preventable factors in 256 dog bite-related fatalities in the United States (2000-2009). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2013;243(12):1726-1736.

- Baldry AC. Animal abuse among preadolescents directly and indirectly victimized at school and at home. Crim Behav Ment Health 2005;15(2):97-110.

- Becker KD, Herrera J, McCloskey LA. A study of fire setting and animal cruelty in children: Family influences and adolescent outcomes. JAACAP 2004;43:905-912.

- Ascione FR, McCabe MS, Philips A, et al. Animal abuse and developmental psychopathology: Recent research, programmatic and therapeutic issues and challenges for the future. In; Fine AH (ed.), Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice (3rd ed.) London, Elsevier; 2010;357-400.

- Baldry AC. The development of the P.E.T. scale for the measurement of physical and emotional tormenting against animals in adolescents. Soc Animals 2004;12(1):1-17.

- Ascione FR. Animal abuse and youth violence. Washington DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention 2001;2-17.

- Hensley C, Tallichet SE. Animal cruelty motivations. Assessing demographic and situational influences. J Interpers Violence 2005;20(11):1429-1443.

- Ascione FR, Shapiro K. People and animals, kindness and cruelty: Research directions and policy implications. J Social Issues 2009;65(3):569-587.

- Wright J, Hensley C. From animal cruelty to serial murder: Applying the graduation hypothesis. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 2003;57(1):71-88.

- Ascione FR, Friedrich WN, Heath WN, et al. Cruelty to animals in normative, sexually abused, and outpatients psychiatric samples of 6 to 12 year-old children; relations to maltreatment and exposure to domestic violence. Anthrozoös 2003;16(3):194-212.

- Arluke A, Luke L. Physical cruelty towards animals in Massachusetts 1975-1996. Soc Anim 1997;5(3):195-204.

- Kellert SR, Felthous AR. Childhood cruelty towards animals among criminals and non-criminals. Humans Relations 1985;38:1113-1129.

- Ascione FR, Thompson TM, Black T. Childhood cruelty to animals: assessing cruelty dimensions and motivations. Anthrozoös 1997;10:170-177.

- Benetato MA, Reisman R, McCobb E. The veterinarian’s role in animal cruelty cases. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2011;238(1):31-34.

- Tong L. Identifying non-accidental injury cases in veterinary practice. In Practice 2016;38:59-68.

- Jordan T, Lem M. One health, one welfare: education in practice – veterinary students’ experiences with community veterinary outreach. Can Vet J 2014;55:1203-1206.

- Ascione FR, Weber CV, Thompson TM, et al. Battered pets and domestic violence. Animal abuse reported by women experiencing intimate violence and by non-abused women. Violence Against Women 2007;13:354-373.

- Garcia Pinillos R, Appleby M, Manteca X, et al. One Welfare – a platform for improving human and animal welfare. Vet Rec 2016;179:412-413.

- Munro, HMC, Thrusfield MV. Battered pets: non-accidental physical injuries found in dogs and cats. J Small Anim Pract 2001;42:279-290.

- Arkow P. Recognizing and responding to cases of suspected animal cruelty, abuse, and neglect: what the veterinarian needs to know. Vet Med Res Rep 2015;6:349-359.

- Deviney E, Dickert J, Lockwood R. The care of pets within child abusing families. Int J Study Anim Probl 1983;4:321-329.

Other articles in this issue

Share on social media