Dental disease in dogs and cats

Written by Javier Collados

Detection of dental disease requires an initial oral examination, followed by a definitive oral examination under general anesthesia. Suitable dental instruments (e.g. explorer, periodontal probe) along with additional diagnostic tests as necessary (such as dental radiographs) are essential for accurate diagnosis.

Key points

Detection of dental disease requires an initial oral examination, followed by a definitive oral examination under general anesthesia.

Suitable dental instruments (e.g. explorer, periodontal probe) along with additional diagnostic tests as necessary (such as dental radiographs) are essential for accurate diagnosis.

Abrasion

Loss of dental tissue through abnormal mechanical action, caused by foreign objects in the oral cavity (e.g. tennis balls, stones, cage bars).

- Prevalence: common in dogs; rare in cats.

- Diagnosis: visual examination and dental explorer.

- Key point: use an explorer to assess if pulp exposure is present. Determine whether the change in color on the occlusal surface of an affected tooth is due to tertiary dentine (brown discoloration) or pulp exposure (black discoloration).

Abnormal attrition

Physiological loss of dental tissue due to contact between the occlusal surfaces of the teeth during mastication. Usually mild but in some cases (e.g. certain malocclusions) can become abnormal and severe.

- Prevalence: relatively common in dogs; sometimes seen in cats.

- Diagnosis: visual examination and dental explorer.

- Key point: as with abrasions, it is essential to use an explorer to assess whether or not pulp exposure is present. Dental radiology may be necessary to determine the extent of the disease.

Dental caries

Demineralization and destruction of calcified tooth tissue caused by bacteria.

- Prevalence: uncommon in dogs, extremely rare in cats.

- Diagnosis: visual examination, explorer and dental radiography (to determine the extent of the lesion).

- Key point: the most commonly affected tooth in dogs is the maxillary first molar. Always examine the first, second and third mandibular molars if the first maxillary molar is affected, as they occlude with it and can also be affected.

Tooth discoloration

A color change (which can vary markedly) on part or all of the crown of the tooth. It can accompany, and be related to, other dental diseases (e.g. tooth fracture).

- Prevalence: relatively common in dogs, occasionally seen in cats (relatively common in conjunction with complicated fractures).

- Diagnosis: visual examination.

- Key point: etiology varies (e.g. trauma, physical, chemical), and the pulp may be necrotic, so dental radiography is always indicated.

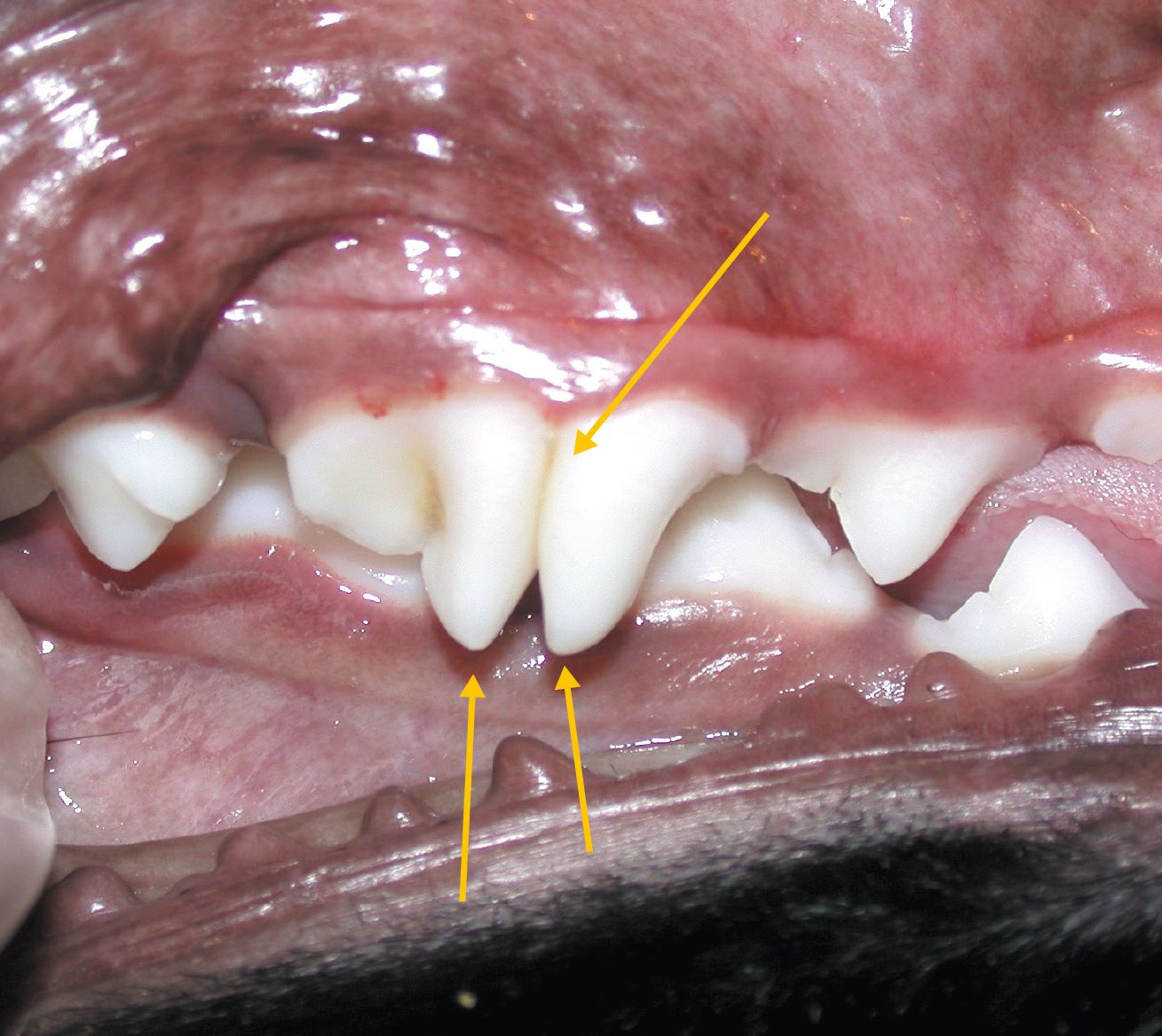

Fusion

Where the dentine of two individual teeth fuses together, leading to fewer teeth than normal.

- Prevalence: uncommon in dogs, very rare in cats.

- Diagnosis: visual examination and explorer.

- Key point: severe morphological change can lead to pulp pathologies. Dental radiography is indicated.

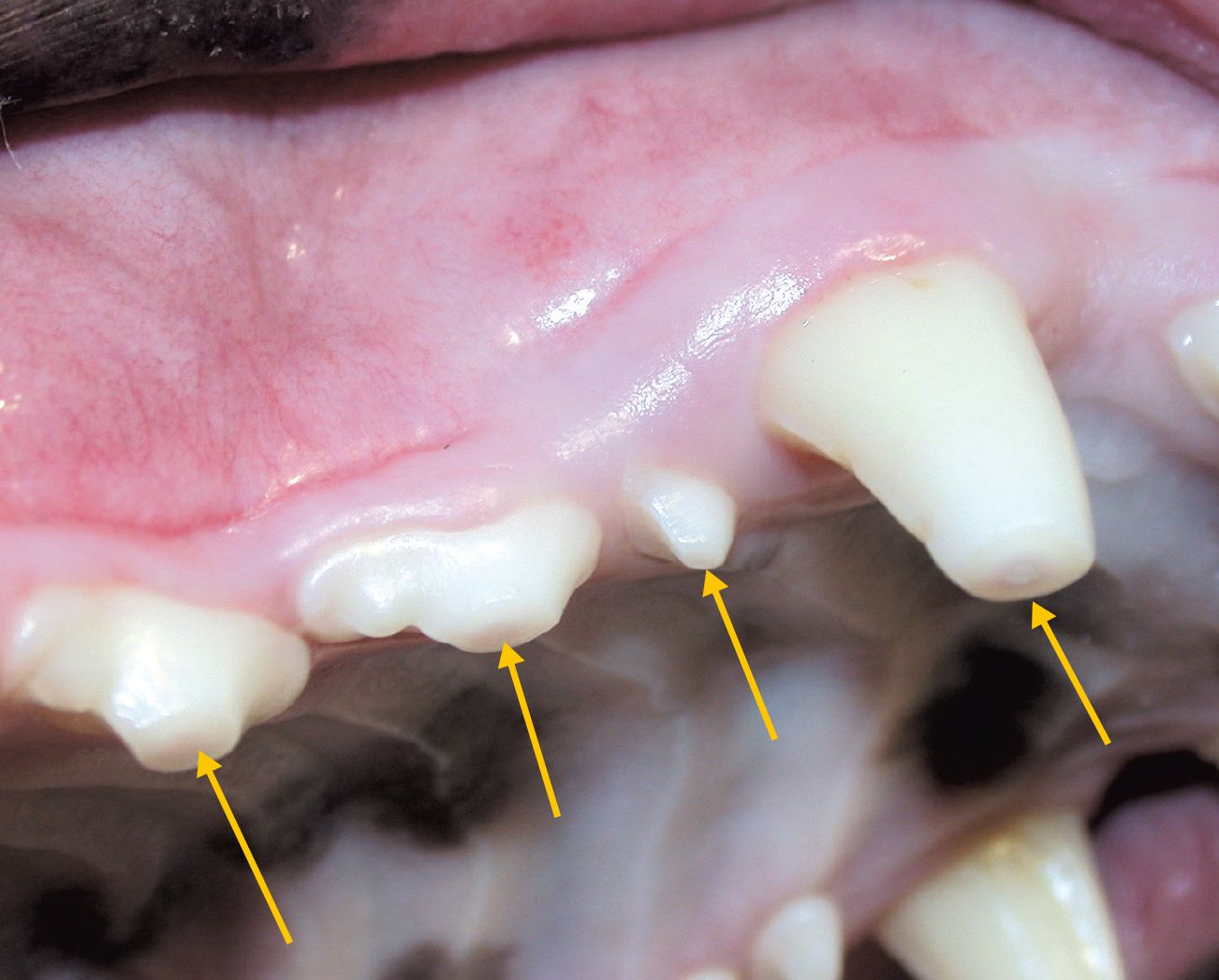

Microdontia

A change in the size of a tooth, whereby affected teeth are smaller than normal. If multirooted teeth are involved, the number of roots are often altered.

- Prevalence: uncommon in dogs, very rare in cats.

- Diagnosis: visual examination.

- Key points: dental radiography to detect any changes in the shape and number of roots is indicated.

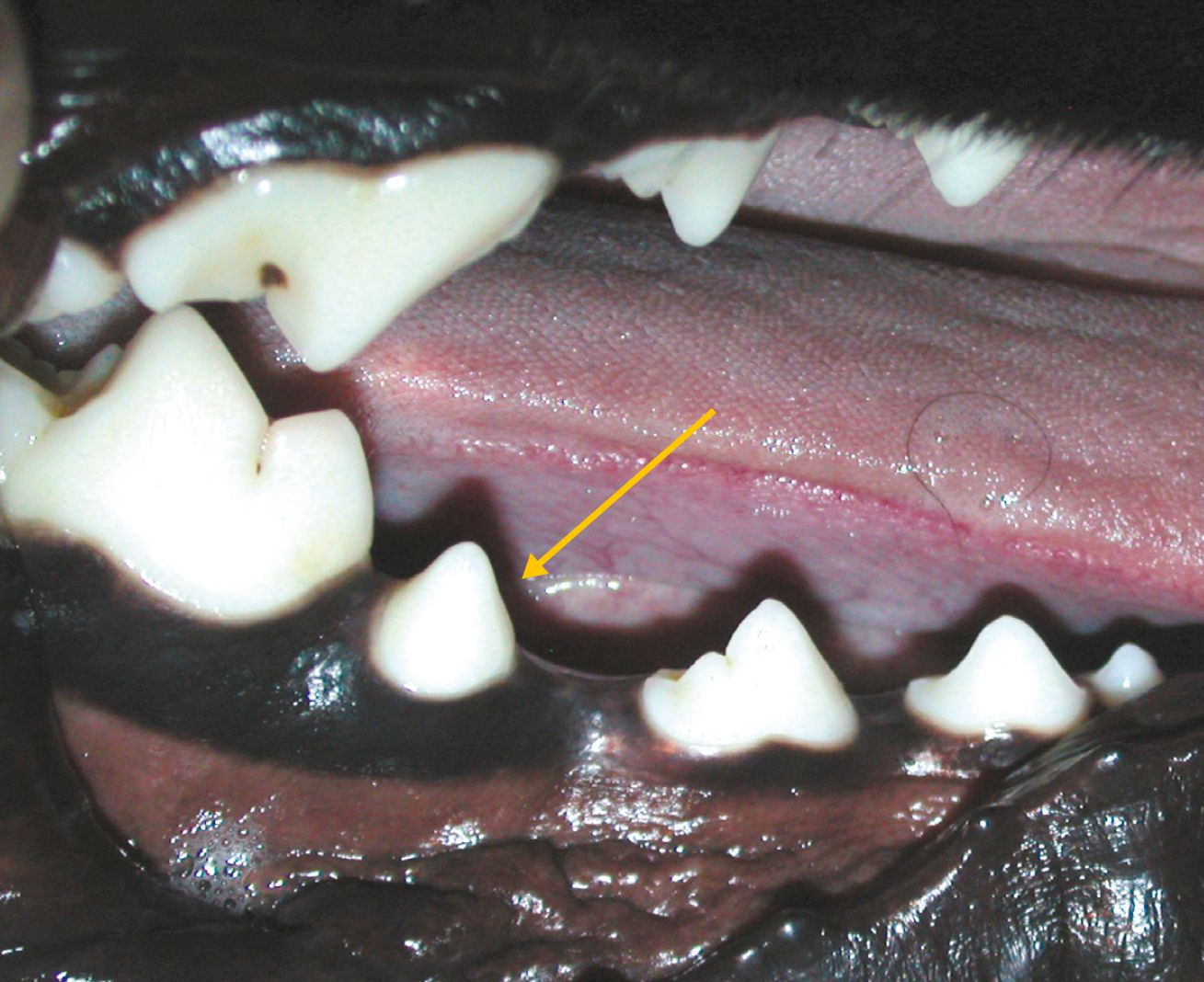

Gemination

Where two teeth try to develop from the same bud. Usually a tooth has two crowns, separated by a crack. There is no reduction in the number of teeth.

- Prevalence: uncommon in dogs, very rare in cats.

- Diagnosis: visual examination and explorer.

- Key point: the morphological change can lead to pulp pathologies. Monitoring using radiography is always indicated.

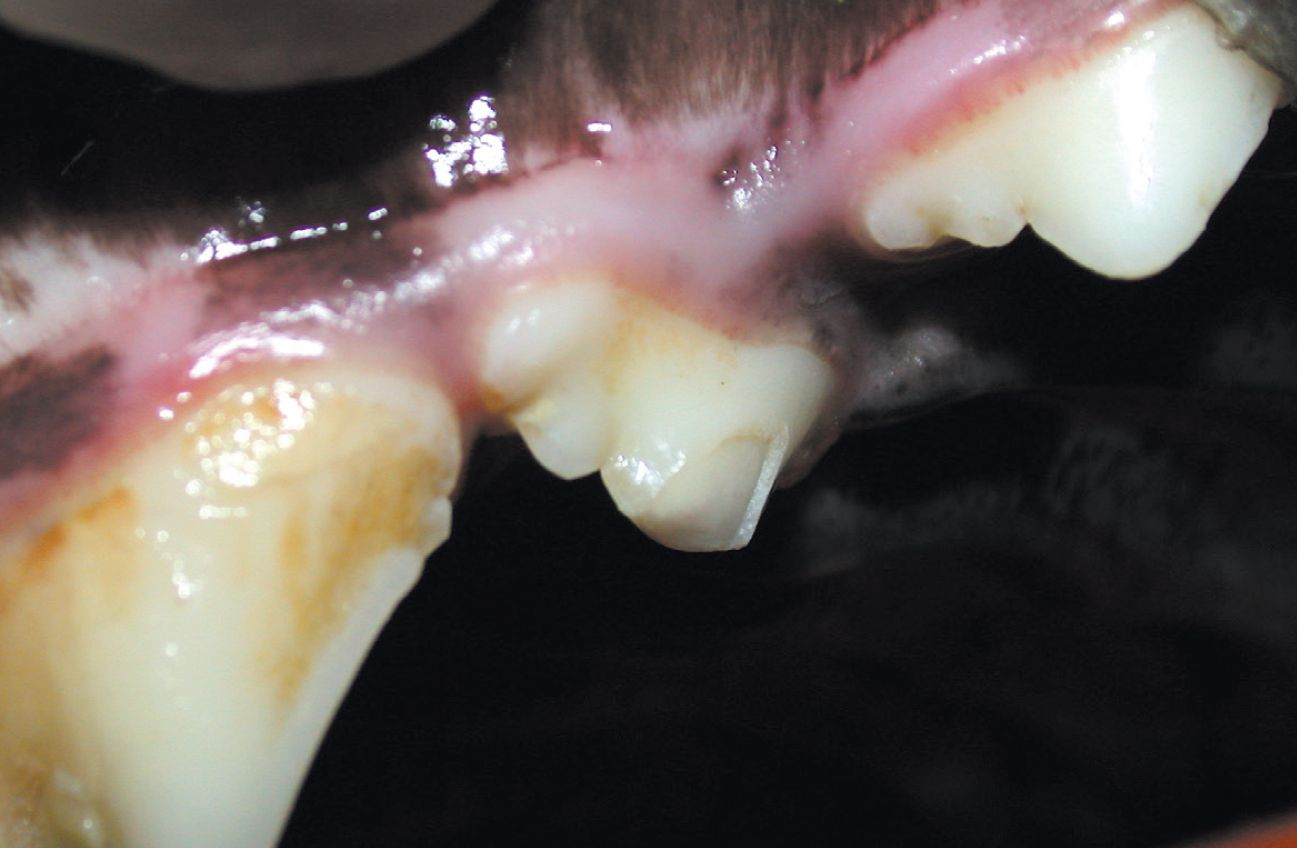

Enamel hypoplasia

A defect in amelogenesis (enamel development) whereby insufficient enamel is deposited.

- Prevalence: relatively common in dogs, very rare in cats.

- Diagnosis: visual examination and explorer.

- Key point: should not be confused with enamel hypomineralization (amelogenesis alteration with inappropriate mineralization of the enamel). Etiology varies; the most common are viral infections and localized trauma.

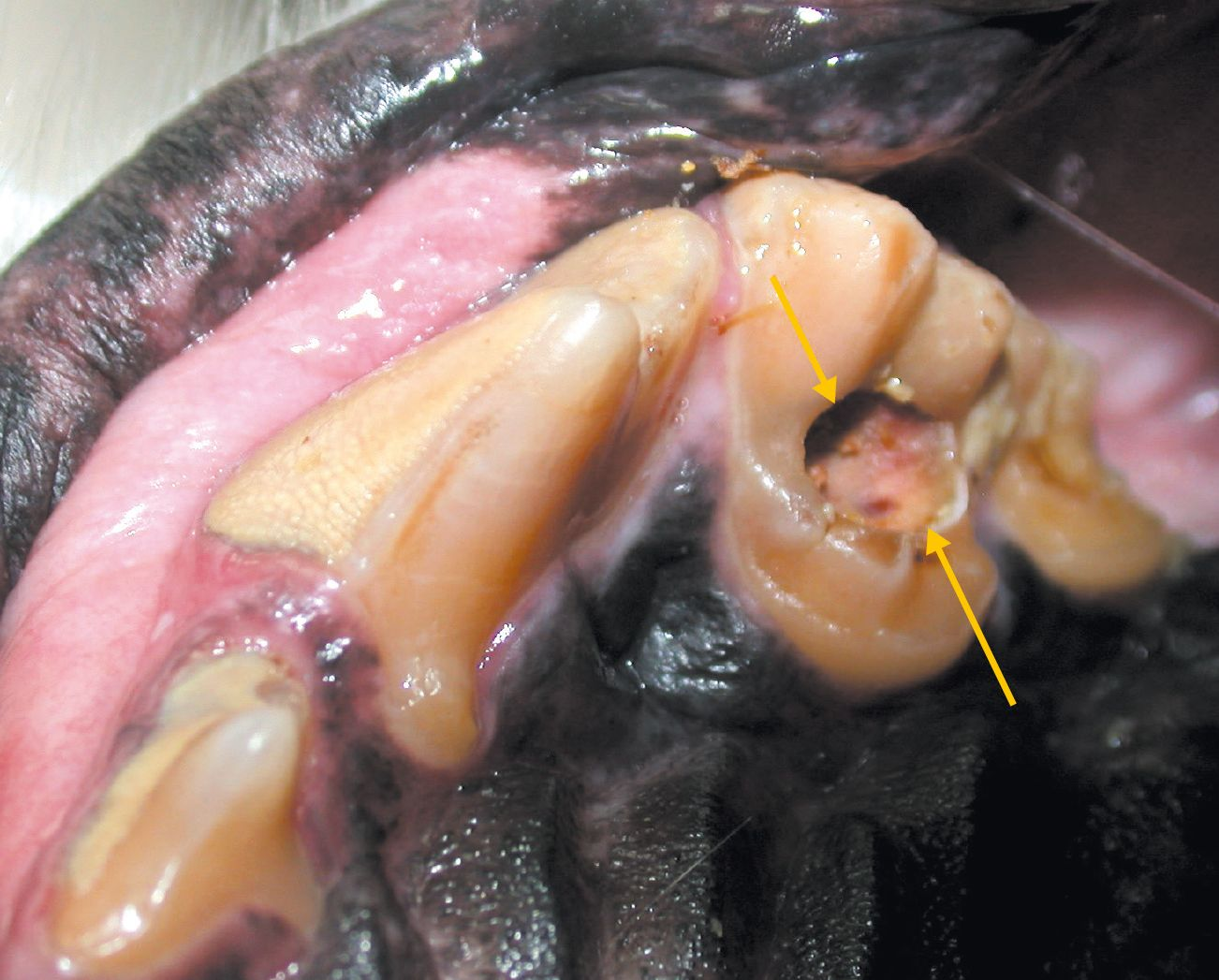

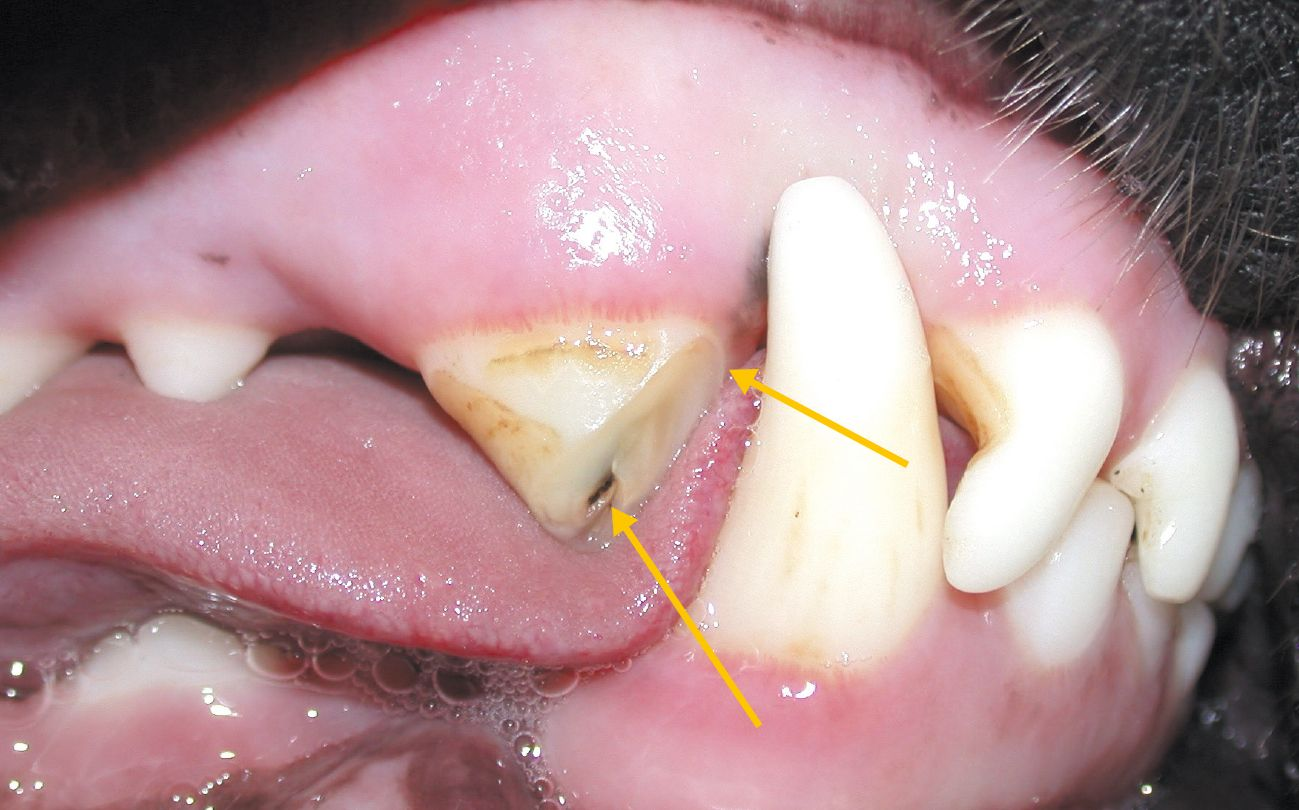

Resorption

Progressive destruction of permanent tooth tissue, due to the action of clastic cells. The etiology is complex and has not yet been clearly defined.

- Prevalence: uncommon in dogs but common in cats (feline oral resorption lesion - FORL).

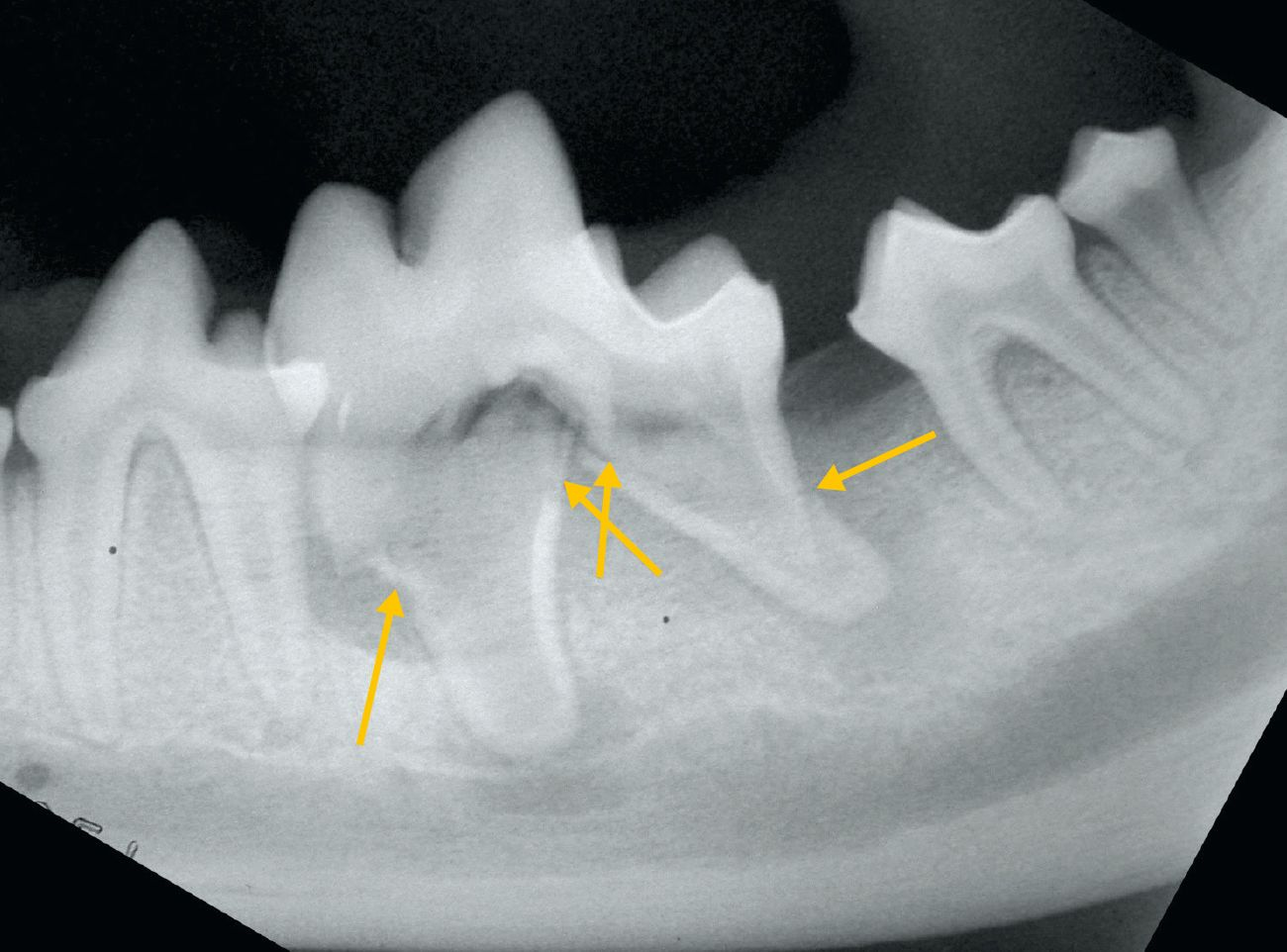

- Diagnosis: visual examination, explorer and dental radiography.

- Key points: radiography is essential to assess the extent of the lesion, allow classification and permit formulation of a treatment plan.

Dental fractures*

*Abbreviations refer to American Veterinary Dental College tooth fracture classification system

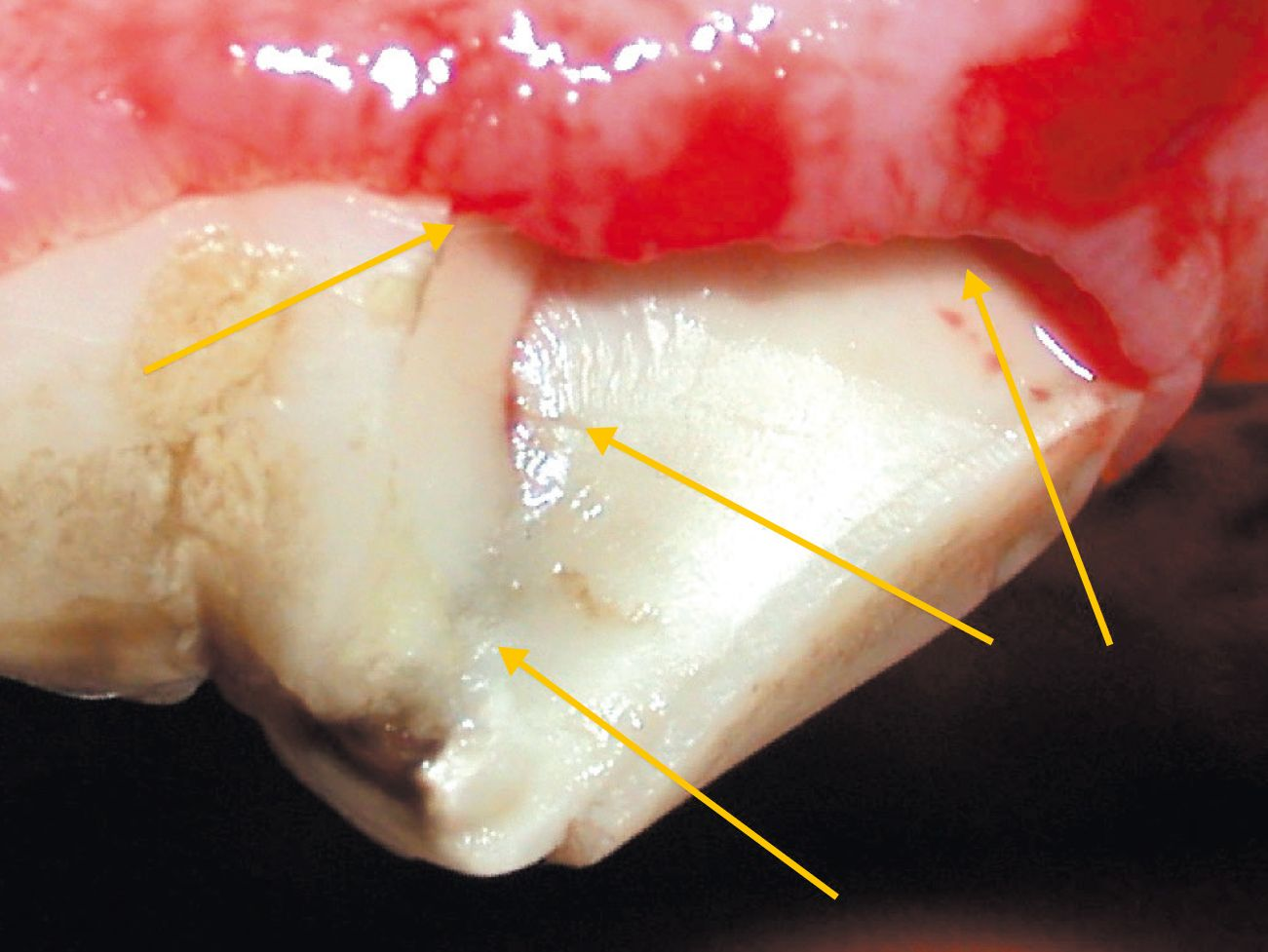

Enamel infraction (EI)

A fracture or crack in the enamel without loss of substance.

- Prevalence: uncommon in dogs, very uncommon in cats (cannot be detected with the naked eye).

- Diagnosis: visual examination.

- Key point: pulp pathology is unlikely but a dental radiography is indicated.

Enamel fracture (EF)

A fracture affecting only the enamel with loss of substance.

- Prevalence: relatively common in dogs, relatively uncommon in cats.

- Diagnosis: visual examination and explorer.

- Key point: the use of an explorer may be necessary to differentiate it from other types of fractures (e.g. an uncomplicated crown fracture). Dental radiography is indicated.

Uncomplicated crown fracture (UCF)

A fracture of the crown without pulp exposure.

- Prevalence: relatively common in both dogs and cats.

- Diagnosis: visual examination and explorer.

- Key point: radiography is indicated; appropriate treatment (e.g. indirect pulp cap) may be necessary.

Uncomplicated crown-root fracture (UCRF)

Fracture of the crown and root without pulp exposure.

- Prevalence: relatively uncommon in dogs, rare in cats.

- Diagnosis: visual examination, explorer and dental radiography (to determine the extent of the damage).

- Key point: dental radiography if the periodontal area is compromised; appropriate treatment (root canal and/or periodontal treatment) may be indicated.

Complicated crown fracture (CCF)

Fracture of the crown with pulp exposure.

- Prevalence: common in both dogs and cats.

- Diagnosis: visual examination and explorer.

- Key point: after dental radiography, treatment is essential (root canal treatment or extraction).

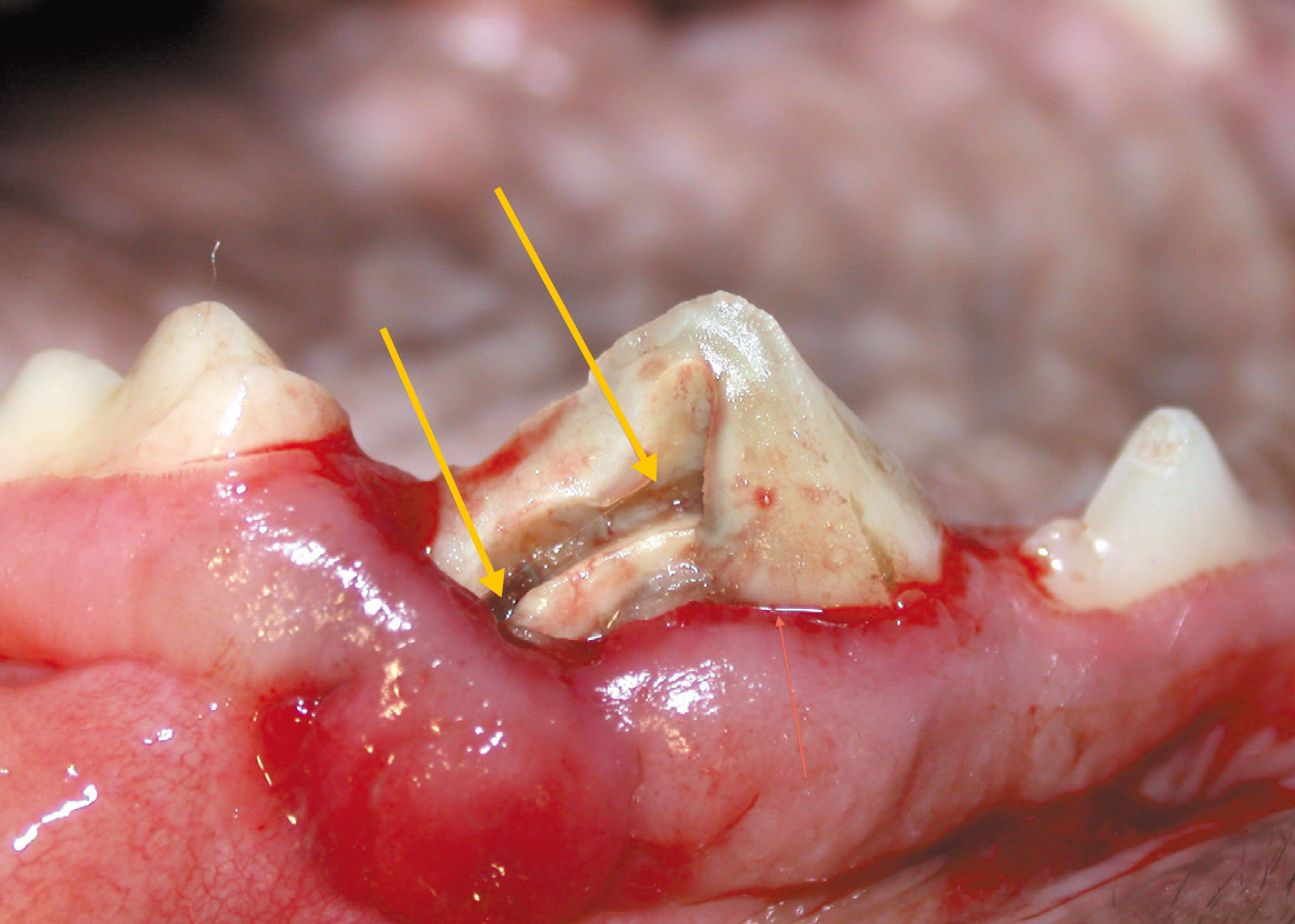

Complicated crown-root fracture (CCRF)

A fracture of both crown and root with pulp exposure.

- Prevalence: common in both dogs and cats.

- Diagnosis: visual examination, explorer and dental radiography (to determine the extent of the damage).

- Key point: following dental radiography, treatment is essential (root canal and periodontic treatment if feasible, or extraction).

Root fracture (RF)

Fracture of the dental root alone.

- Prevalence: relatively uncommon in dogs, rare in cats.

- Diagnosis: explorer (to assess the degree of crown movement) and dental radiography.

- Key point: dental radiography for the diagnosis is essential. Treatment is extraction.

Javier Collados

DVM, PhD, MRCVS

Spain

Dr. Collados graduated in Veterinary Medicine from the Complutense University of Madrid in 1994 and earned a PhD from the same university in 2021. He completed a residency at the American Veterinary Dental College (AVDC). He was the only AVEPA certified in Dentistry and Oral Surgery in 2013, working exclusively in this field. He heads the Dentistry and Oral Surgery service at Sinergia Veterinaria. He was a lecturer and subject coordinator in Animal Dentistry at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of the Alfonso X el Sabio University of Madrid.

He has authored numerous publications and, more particularly, the Visual Atlas of Oral and Dental Pathologies in Exotic and Small Animals (Ed. Servet, 2008), translated into Spanish, French and Japanese. He has spoken at national and international courses and congresses, and has participated in more than 100 events.

Other articles in this issu

Share on social media