Feline cutaneous adverse food reactions

Written by Sarah E. Hoff and Darren J. Berger

Owners are often keen to blame their cat’s diet if their pet develops a skin problem, but is this correct? In this article the authors discuss appropriate methods for the diagnosis and treatment of adverse food reactions.

Key points

Cutaneous adverse food reaction in cats is indistinguishable from other allergic hypersensitivities on the basis of clinical presentation and lesion location.

Non-seasonal pruritus is the most common clinical sign associated with an adverse food reaction.

An adverse food reaction can only be accurately diagnosed through an elimination diet trial utilizing a balanced home-cooked diet, prescription novel protein or hydrolyzed diet for at least 8 weeks.

Client education will improve compliance with diet elimination trials and can be key to successful diagnosis and treatment.

Introduction

A common misconception amongst pet owners is that clinical signs of a food allergy occur soon after a change of diet. While adverse reactions to foods can occur shortly after a new diet is introduced, such reactions are rarely allergic in nature because of the time required to develop an immunologic response, and it is important to educate owners on the distinction between food intolerance and food allergy. Food intolerance represents any abnormal physiological response that is not immunologically mediated to a component, toxin, or product in the food that results in an undesirable side effect [1]. The most common example is lactose intolerance, in which the inability to digest lactose results in hyper-osmotic diarrhea and subsequent flatulence, abdominal discomfort and diarrhea. Food allergy, on the other hand, refers to an immunological reaction to a component in a food, and may be either an immediate type I hypersensitivity reaction, mediated through IgE, or a delayed type hypersensitivity, mediated through lymphocytes and their cytokines [1]. In animals the distinction between food intolerance and food allergy may be difficult to make, and thus the term “adverse food reaction” has been proposed to encompass all etiologies that result in a clinically abnormal response attributable to the ingestion of a food substance [2]. In the cat, adverse food reactions most commonly manifest as skin disease and gastrointestinal disease, although more rarely they can result in conjunctivitis, rhinitis, neurological signs, and behavioral abnormalities [1] [3]. This article will primarily discuss manifestations of cutaneous adverse food reactions (CAFR).While adverse reactions to foods can occur shortly after a new diet is introduced, such reactions are rarely allergic in nature because of the time required to develop an immunologic response, and it is important to educate owners on the distinction between food intolerance and food allergies.

Initial investigations for CAFR

CAFR is a relatively uncommon diagnosis in cats, with the overall reported prevalence ranging from 0.2-6%, although prevalence greatly increases amongst cats presenting to a veterinarian for a primary complaint of pruritus (12-21%) or allergic skin disease (5-13%) [4], and a structured approach to diagnosis is essential.

History and clinical presentation

In order to make an accurate diagnosis and treatment plan, the importance of obtaining a complete history cannot be understated; this includes a thorough diet history, which helps to determine previous exposures and guide future treatments. Examples of important questions to ask owners regarding their cat’s skin disease are listed in Table 1, and information gained from a thorough history can narrow the differential list and help guide next steps. For example, the absence of a regular flea control program may make flea allergy dermatitis a primary differential, and if multiple animals from a household are displaying clinical signs a contagious parasite or pathogen is more likely.

| Medical history | Diet history | Lifestyle | Medication use |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Clinical signs of CAFR can appear at any age but are most commonly seen in young to middle aged cats, with an average age at onset of 3.9 years, and there does not appear to be a clear breed or sex predilection [5]. The most frequent clinical sign is non-seasonal pruritus [5], with a variable prevalence of concurrent gastrointestinal signs, reported at around 17-22% of affected cats [2]. When present, the most common gastrointestinal sign associated with an adverse food reaction is vomiting, followed by flatulence and diarrhea [3].

Previous response to therapy can be variable. One study reported that all 17 cats diagnosed with CAFR had at least a partial response to either systemic or topical glucocorticoids [6], but another retrospective study of 48 affected cats noted that systemic glucocorticoids were ineffective in 61% of cases [7]. In a third study of 10 cats with CAFR, owners reported no benefit from injectable long-acting glucocorticoids [8].

Physical examination

Physical exam may reveal one of several cutaneous reaction patterns: lesion-less pruritus, self-induced alopecia (Figure 1), miliary dermatitis (Figure 2), and lesions of eosinophilic skin diseases, namely indolent ulcers, eosinophilic plaques and eosinophilic granulomas (Figures 3 and 4) [2]. The areas most commonly affected include the face/head, ears, ventrum, and feet [5], but these signs are not pathognomonic for CAFR and there are many other disease processes that can produce identical signs (Table 2). Part of the physical examination should include a thorough brushing with a flea comb to look for evidence of fleas, lice, and mites (Cheyletiella spp.), although the absence of fleas (and flea dirt) does not exclude the parasite, as cats are efficient groomers and may remove all evidence of fleas.

| Differential diagnoses | Recommended diagnostics |

|---|---|

| Flea allergy dermatitis | Physical examination, flea comb, response to parasite control, fecal flotation, evidence of tapeworms |

| Demodex gatoi | Skin scraping, fecal flotation, response to treatment |

| Cheyletiella spp. | Physical examination, skin cytology, skin scraping, flea comb, fecal flotation |

| Otodectes cynotis or Notoedres cati | Physical examination, skin/ear cytology, skin scraping |

| Dermatophytosis | History, trichogram, Wood’s lamp, DTM culture, fungal PCR |

| Autoimmune diseases (pemphigus foliaceus) | Skin cytology, biopsy and histopathology |

| Endocrinopathies (hyperthyroidism, diabetes, etc.) | History, bloodwork and urinalysis |

| Cutaneous adverse drug reaction | History, biopsy and histopathology |

| Viral diseases (herpesvirus, papillomavirus, calicivirus, poxvirus, feline leukemia virus) | Biopsy and histopathology, PCR, immunohistochemistry |

| Non-flea, non-food induced hypersensitivity dermatitis (NFNFIHD) | History, excluding other differentials |

| Psychogenic alopecia | History, response to treatment, excluding all other differentials |

Dermatological database

As CAFR is a relatively uncommon diagnosis, appropriate diagnostics and therapies should be performed to rule out as many differentials as possible. A dermatological database (skin scraping, cytology, trichogram and fecal flotation) should be performed at initial presentation to exclude conditions that can present similarly to CAFR as well as to identify any secondary infections or parasitic infestations. Cats may have secondary bacterial or Malassezia infections which can exacerbate pruritus caused by the underlying condition [6]. If not previously performed, a fungal culture or ringworm PCR should be considered, as feline dermatophytosis commonly presents with lesions affecting the head and neck as well as variable pruritus [9]. Although traditionally thought to be a contagious disease, individual animals can be more susceptible to dermatophyte infections, and other animals may be asymptomatic carriers [9], so the absence of multiple animals or humans displaying clinical signs does not exclude dermatophytes as a potential underlying cause.Specific CAFR diagnostics

Once other diseases have been ruled out, a diagnostic test for CAFR that is simple to perform, relatively inexpensive, and gives an accurate diagnosis would be ideal. However, to date no such test has been found to meet these criteria [10]. There are however various proposed tests for CAFR.

Histopathology

While skin biopsies are useful for the diagnosis of many skin diseases and may aid in eliminating some differentials, there are no pathognomonic findings to definitively diagnose CAFR. Biopsy of animals with CAFR usually demonstrate a perivascular dermatitis characterized by a variable cellular infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, eosinophils, mast cells, neutrophils, and macrophages. However, these changes are nonspecific and can be seen with any allergic etiology, so biopsies of animals with CAFR, flea allergy dermatitis, and non-flea, non-food-induced hypersensitivity dermatitis (NFNFIHD) will all exhibit similar changes. Skin biopsy alone cannot therefore distinguish between these allergic etiologies, and likewise intestinal biopsies of animals with concurrent gastrointestinal signs will give a histologic diagnosis but not an etiological diagnosis, and cannot distinguish between animals with adverse food reactions and non-food reactions [10].

Serum IgE tests

Skin prick and patch testing

Hair and saliva analysis

Studies have shown that hair and saliva analysis are not reproducible, as duplicate samples from the same animal result in disparate results [13]. Furthermore, such tests have been unable to distinguish between allergic and non-allergic dogs, nor can they distinguish between inanimate (e.g., teddy bear fibers) and living samples [13]. A recent study that evaluated the specificity, sensitivity, and positive and negative predictive values of saliva testing found that overall the results were too low to recommend their use for CAFR diagnosis [2].

Elimination diet trial

The only method that has been shown to be a reliable diagnostic tool for diagnosis of an adverse food reaction is an elimination diet trial [10]. The theory is that removal of the offending agent from the animal’s diet should result in an improvement of clinical signs, although one of the most challenging aspects is determining what antigen is stimulating an individual animal’s clinical signs. Through individual constituent provocation tests, the ingredients most likely to result in an adverse reaction in cats as identified by a recent literature review were beef, fish, and chicken [2], and the choice of an elimination diet would ideally avoid such ingredients.

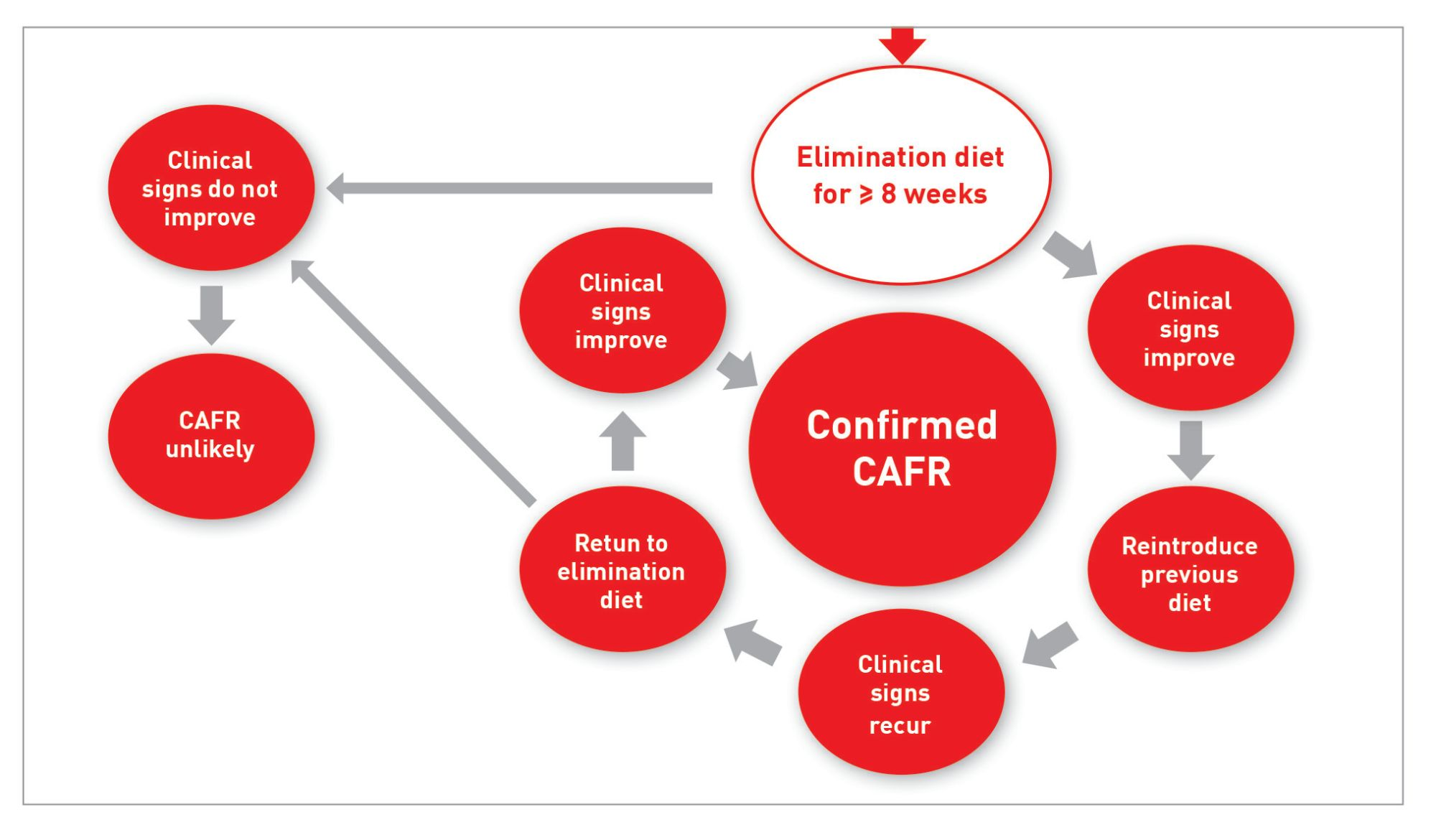

Confirmation of an adverse food reaction is a multi-step process (Box 1). Firstly, the cat has to eat the elimination diet for a specified period of time and exhibit an improvement in clinical signs. A recent review of published studies concluded that up to 90% of cats with an eventual diagnosis of CAFR will experience a remission in their clinical signs by 8 weeks, therefore the current recommendation is that an elimination diet trial should be for at least this period in order to maximize the likelihood of correctly identifying an affected animal [14]. To confirm that the food has been responsible for remission of the clinical signs, the cat’s diet then needs to be “challenged” by adding some of the old diet to the elimination diet. Most cats with an adverse food reaction will exhibit an exacerbation of clinical signs within 2-3 days, but this has been reported to take up to 14 days in some cases [6]. Some animals may improve on the elimination diet but fail to relapse when challenged with the previous diet, and in these circumstances the initial improvement may be attributable to other therapies such as flea control or treatment of secondary infections, the improved quality of fatty acids and proteins in the elimination diet, or a change of season [2]. If the cat worsens when exposed to the previous diet, the elimination diet is then fed exclusively again. If the clinical signs subsequently improve, a diagnosis of CAFR is confirmed. In order to identify the specific offending allergen, different foods may be added weekly or biweekly and the animal observed for an exacerbation of the clinical signs.

The three choices for an elimination diet trial are a home-cooked diet using a novel protein and carbohydrate source, a commercial novel protein diet, or a commercial hydrolyzed protein diet.

Home-cooked options for diet elimination trials offer the opportunity to eliminate the possibility of confounding ingredients (e.g., corn starch, by-products, etc.) [1]. Although a small retrospective study has reported that such diets were more sensitive for the diagnosis of feline CAFR [6], a thorough dietary history is needed to ensure that both the protein source and the carbohydrate source are truly novel (i.e., never eaten before). Home-cooked diets are more labor intensive and require consultation with a veterinary nutritionist to ensure that the diet is balanced in order to avoid adverse events associated with nutritional deficiencies. As a result, practitioners and owners may elect to pursue a trial with a commercial prescription diet to avoid such potential complications.

Certain commercial novel protein diets are a good alternative, especially if owners are unwilling or unable to cook for their pet. As with home-cooked diets, it is important to obtain a full dietary history to avoid selecting a protein source to which the cat has previously been exposed. However, the origin of the diet should also be given consideration; owners will sometimes seek over-the-counter (instead of “prescription”) diets which are often labelled as having “limited ingredients” or “novel protein”, but many of them have not undergone testing to ensure their purity, and have been shown to contain ingredients not listed on the label [15]. Such unidentified ingredients can negate the benefit from changing the main protein source, as animals may have sensitivities to these contaminants [15]. Even raw diets have been found to have similar mislabeling concerns [16], so over-the-counter diets are not acceptable for elimination diet trials. At this time only appropriate prescription diets should be considered an acceptable choice for such trials.

Owners will sometimes seek over-the-counter diets which are often labelled as being “limited ingredients” or “novel protein”, but many of these have not undergone testing to ensure their purity, and have been shown to contain ingredients not listed on the label.

An additional complicating factor is that there are many reports of cross-reactivity between proteins, so finding a truly novel protein may be challenging. It has been shown that there are common allergens amongst avian species, so feeding a duck diet to an animal previously exposed to chicken may not be a truly novel protein source [17]. It has also been hypothesized that cross-sensitizations exist amongst ruminant species, meaning that for an animal previously exposed to beef, certain ingredients such as lamb, venison, and bison may not be truly novel [18].

For these reasons many veterinarians will utilize prescription hydrolyzed protein diets, where processing produces peptide segments that are anticipated to be small enough to prevent cross-linking of mast cells which would otherwise result in an allergic response. In people, food allergens typically have a molecular weight of around 10-70 kDa [1] but the size of peptide required to minimize the possibility of an allergic response in animals is yet to be determined. There is the potential that an animal may react to the parent protein if the hydrolysate offered is not small enough, and it is recognized that peptide size can vary between different diets. Along these lines, a crossover study of ten known chicken-allergic dogs compared two hydrolyzed diets with different parent proteins and hydrolysis methods (extensively hydrolyzed poultry feathers and hydrolyzed chicken livers). Owners were asked to score the degree of pruritus, and 4 out of the 10 dogs exhibited an increase in pruritus when fed the hydrolyzed chicken liver diet, whereas none flared when fed the extensively hydrolyzed poultry feather diet [19]. To date, no such study has been conducted in cats, with one challenge being that many of these diets may not be palatable to cats. The small peptide size also introduces the risk that hyper-osmotic diarrhea may develop in animals fed such a diet [20].

Some recent studies have brought into question the ability of hydrolyzed protein diets to accurately diagnose CAFR in dogs and cats. The report referred to above [6] found that 50% of cats in the study could not be diagnosed using a hydrolyzed diet and required a home-cooked recipe for accurate diagnosis of CAFR, although this was a small retrospective study and a variety of elimination diets were employed. A study evaluating the reactivity of lymphocytes of dogs with CAFR to residual proteins and peptides (>1 kDa) in two commercial hydrolyzed protein diets found that the residual proteins stimulated lymphocyte activity in approximately 30% of cases [21], although as this was an in vitro study it is unknown if this finding is clinically significant. However, given the limited number of novel proteins available, potential cross-reactions between protein sources, and the challenges in formulating and preparing home-made diets, hydrolyzed protein diets still remain a good option for use in an elimination diet trial.

Client education for maximizing compliance

One of the challenges with elimination diet trials is that they rely on the owners to ensure accurate completion. A recent survey of dog owners reported that almost 60% did not strictly adhere to the elimination diet, with reasons that included perceived barriers such as lifestyle, cost or ability to administer medications [22]. Owners were however more likely to be compliant if they had knowledge regarding diets and CAFRs, and such observations underscore the importance of communication and client education when recommending a diet trial.

Finding an elimination diet that a cat will eat may be challenging in itself. It is important to stay in contact with the owners during a trial, and for them to carefully monitor their pet’s eating habits, as problems such as hepatic lipidosis can develop in anorectic cats [2]. It may take more than one attempt to find a suitable diet for the trial. For multiple cat households, feeding an elimination diet to only the affected cat can also be problematic. Commercial prescription diets are well-balanced and labelled for maintenance of adult cats, and can therefore be appropriate to feed to all cats. If owners wish to limit the cost associated with the prescription diet and feed only the affected cat, the cat may be separated for feeding or a microchip feeder (which will open only for an individual animal to eat) may be utilized.

Control of pruritus

Long-term prognosis

If a cat previously diagnosed with a CAFR exhibits new cutaneous signs, it is possible that they have developed concurrent NFNFIHD or flea allergy dermatitis. In fact, concurrent NFNFIHD and CAFR is more common in the cat than concurrent CAFR and atopy in the dog [24], with one study reporting that up to 50% of cats with CAFR were also diagnosed with NFNFIHD [6]. The same initial diagnostic evaluation utilized for CAFR will be useful to rule out any mimickers of allergic disease.

Conclusion

Sarah E. Hoff

DVM, MPH

Dr. Hoff completed a Masters of Public Health in epidemiology prior to attending veterinary school at the University of Missouri. After graduation she spent three years in small animal general practice before pursuing specialization in dermatology. She is currently a third-year dermatology resident at Iowa State University.

Darren J. Berger

DVM, Dip. ACVD

Dr. Berger qualified from Iowa State University in 2007 and worked in small animal practice for some years before returning to academia. He is currently an Associate Professor of Dermatology at Iowa State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, with research interests that include clinical pharmacology and the management of allergic hypersensitivity disorders.

References

- Verlinden A, Hesta M, Millet S, et al. Food allergy in dogs and cats: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2006;46:259-273.

- Mueller RS, Olivry T. Critically appraised topic on adverse food reactions of companion animals (4): can we diagnose adverse food reactions in dogs and cats with in vivo or in vitro tests? BMC Vet Res 2017;13;275.

- Pali-Schöll I, De Lucia M, Jackson H, et al. Comparing immediate type food allergy in humans and companion animals – revealing unmet needs. Allergy 2017;72(11):1643-1656.

- Kulis M, Wright BL, Jones SM, et al. Diagnosis, management, and investigational therapies for food allergies. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1132-1142.

- Bernstein JA, Tater K, Bicalho RC, et al. Hair and saliva analysis fails to accurately identify atopic dogs or differentiate real and fake samples. Vet Dermatol 2019;30:105-e128.

- Olivry T, Mueller RS, Prélaud P. Critically appraised topic on adverse food reactions of companion animals (1): duration of elimination diets. BMC Vet Res 2015;11:225.

- Olivry T, Mueller RS. Critically appraised topic on adverse food reactions of companion animals (5): discrepancies between ingredients and labeling in commercial pet foods. BMC Vet Res 2018;14:24.

- Cox A, Defalque V, Udenberg T, et al. Detection of DNA from undeclared animal species in commercial canine and feline raw meat diets using qPCR. In; Abstracts North American Veterinary Dermatology Forum 2019. Vet Dermatol 2019;296.

- Kelso JM, Cockrell GE, Helm RM, et al. Common allergens in avian meats. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;104:202-204.

- Gaschen FP, Merchant SR. Adverse food reactions in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2011;41:361-379.

- Bizikova P, Olivry T. A randomized, double-blinded crossover trial testing the benefit of two hydrolysed poultry-based commercial diets for dogs with spontaneous pruritic chicken allergy. Vet Dermatol 2016;27:289-e270.

- Mueller RS, Unterer S. Adverse food reactions: pathogenesis, clinical signs, diagnosis and alternatives to elimination diets. Vet J 2018;236:89-95.

- Marsella, R. Hypersensitivity Disorders. In; Miller WH, Griffin CE, Campbell KL, et al (eds). Muller Kirk's Small Animal Dermatology 7th ed. St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier/Mosby, 2013;363-431.

- Masuda K, Sato A, Tanaka A, et al. Hydrolyzed diets may stimulate food-reactive lymphocytes in dogs. J Vet Med Sci 2020;82:177-183.

- Painter MR, Tapp T, Painter JE. Use of the Health Belief Model to identify factors associated with owner adherence to elimination diet trial recommendations in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2019;255:446-453.

- Favrot C, Bizikova P, Fischer N, et al. The usefulness of short‐course prednisolone during the initial phase of an elimination diet trial in dogs with food‐induced atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2019;30:498.

- Ravens PA, Xu BJ, Vogelnest LJ. Feline atopic dermatitis: a retrospective study of 45 cases (2001-2012). Vet Dermatol 2014;25:95-e28.

- Mueller RS, Olivry T. Critically appraised topic on adverse food reactions of companion animals (6): prevalence of noncutaneous manifestations of adverse food reactions in dogs and cats. BMC Vet Res 2018;14:341.

- Olivry T, Mueller RS. Critically appraised topic on adverse food reactions of companion animals (3): prevalence of cutaneous adverse food reactions in dogs and cats. BMC Vet Res 2016;13:51.

- Olivry T, Mueller RS. Critically appraised topic on adverse food reactions of companion animals (7): signalment and cutaneous manifestations of dogs and cats with adverse food reactions. BMC Vet Res 2019;15:140.

- Vogelnest LJ, Cheng KY. Cutaneous adverse food reactions in cats: retrospective evaluation of 17 cases in a dermatology referral population (2001-2011). Aust Vet J 2013;91:443-451.

- Scott D, Miller W. Cutaneous food allergy in cats: a retrospective study of 48 cases (1988-2003). Jpn J Vet Dermatol 2013;19:203-210.

- Carlotti D, Remy I, Prost C. Food allergy in dogs and cats; a review and report of 43 cases. Vet Dermatol 1990;1:55-62.

- Moriello KA, Coyner K, Paterson S, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dermatophytosis in dogs and cats: Clinical Consensus Guidelines of the World Association for Veterinary Dermatology. Vet Dermatol 2017;28:266-e268.

Other articles in this issue

Share on social media