Looking to the future

It’s never too early to think about the future. For many young veterinary surgeons, their job is primarily the result of a passion for pets. The concept of “career” doesn’t seem to be adapted to their lifestyle, but this section will explain that having a career plan and living your passion can fit together and even be synergistic.

Key facts

In addition to clinical abilities, skills in communication, leadership and business are essential to your career.

There is no obligation to become a practice owner or partner, you can have a great veterinary career as an employee.

For any challenge, ask yourself the questions: will I be able to do it? Will I be happy to do it?

Many questions about your career will be answered after you have experienced various professional situations.

Managing your professional development

The professional decisions the young vet makes in the first few years of their career, such as in which field to work and how to broaden their training, will have a major economic and professional impact on their future. When making these choices, the young vet should be mindful of the following.

You should learn first in order to profit later

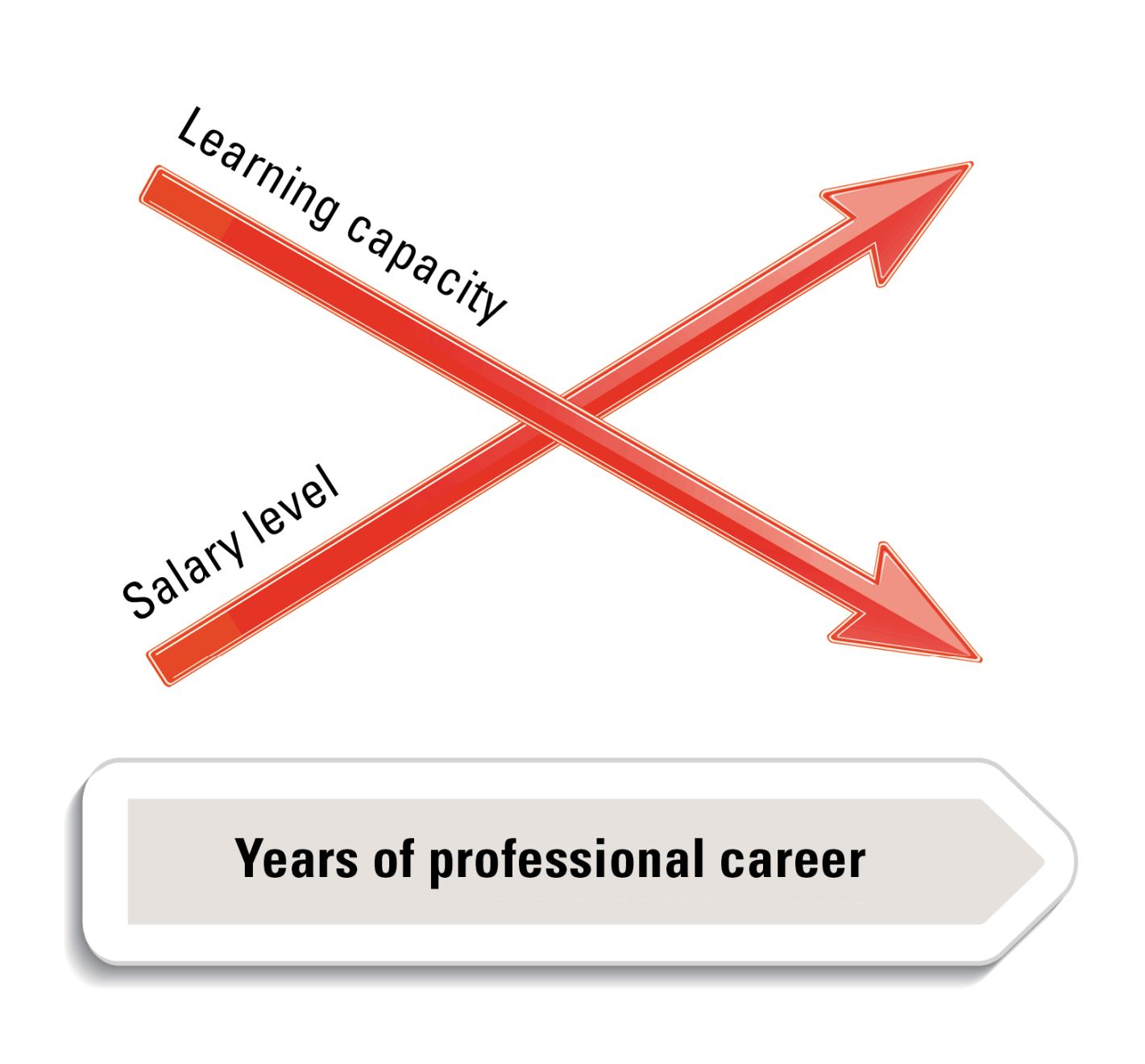

Figure 1 shows the typical career pathway for many professionals. The first years are when the greatest increase in learning takes place. As a young professional, it is the best time to absorb new knowledge, to integrate it and make it take root. However, the greatest salary increases will occur further on in your career, when the accumulated experience, personal and professional prestige, and your knowledge network in the sector often allow a better return on the accumulated investment in your personal career development.

It is therefore a very serious strategic error to ignore the lesson of this graphic and to become focused on small salary increases at the beginning of your professional career. The key question for a young veterinary surgeon with a vision of the future should be “In which of these clinics or alternative roles will I learn the most, so that in five or ten years I’ll be a more valuable professional in the market?”.

The salary differences between a successful professional and a mediocre one are much higher at the end of the professional career than at its beginning. Therefore, what is important is not to make more money in the first half, but in the second half of your career. It is a marathon, and the runner that wants to sprint at the start is at a serious risk of running out of steam on the way.

Balance continuous clinical training with organisational and personal skills

Recognising that for most veterinary surgeons their later career may well involve managing a practice and leading others, there are three areas of knowledge that deserve special attention from the young vet:

- Acquire communication skills. These are essential in order to be successful not only with clients but also with your professional colleagues.

- Acquire leadership skills. This is essential for anyone who aspires to be a team leader in the future.

- Acquire business skills. A good background in finance, strategy and marketing will be an excellent addition to the veterinary surgeon’s technical abilities.

A good background in finance, strategy and marketing will be an excellent addition to the veterinary surgeon’s technical abilities.

Travel and learn languages

In a more global world, the professional that travels and masters languages has a decisive competitive advantage. Being in countries with more developed veterinary sectors and establishing relations with professional leaders from other countries and cultures can mark the difference between an average-level professional and an advanced-level one. The growing tendency in specialisation makes it essential that any vet wishing to stand out in a medical discipline has to travel and interact with centres of excellence wherever they may be in the world (Figure 2).

Specialisation, but with common sense

It is undeniable that veterinary medicine, as with the other health sciences, is tending toward specialisation. As we have discussed, as a young veterinary surgeon you must soon choose if you want to be a good general practitioner or if you wish to follow the demanding and complex path to specialisation. Veterinary medicine, our clients and our patients need both career types so there isn’t only one path to professional success. However, what is clear is that those young vets that decide to chance everything on specialisation will need a bit of luck and a lot of skill when choosing their particular field. They will need to decide which specialities they think will develop most in the upcoming years and which of these has currently the lowest number of suitably qualified professionals, so providing the greatest opportunities. It is a difficult choice, with some suggesting Oncology, or Medical imaging, or Neurology or Gerontology.Setting realistic career goals

Veterinary medicine today offers a wide variety of career options and associated goals. At the beginning of a professional life, it´s not always quite clear where the journey is going and which options will appear along the way. As such, it is always a good idea to look into more than one possibility and not to decide on a whim, or whilst feeling overwhelmed by all the options. Planning and consequently pursuing a career is something that takes time, but it´s worth it!

Do an analysis

Find your fit

Plan steps & goals

When it has become clearer in which direction you want your professional life to head, then it is time to plan the necessary steps that will take you there. In most cases, you will have to build your career in several stages, acquiring knowledge and experience as you move on. Plan your career “top to bottom”, starting with your final goal and then moving down to your current position stage by stage. In this way, you will create a realistic career pathway with achievable steps that stays focused on your final goal.

If you have done your “homework” (consisting of analysing your strengths and weaknesses, and researching different options), then you will find a lot of offers that will take you to your final objective. If you discover that your final goal is not on the market yet, you could take this as an opportunity to invent a new service within the veterinary profession. Everything is possible so long as you conduct thorough research to find out, firstly if your new service is actually wanted by clients (and not just a “brilliant” idea), and secondly, how you would propose to offer this service and to get it into the market.

Investing in or buying out a business

There is no “obligation” to become a practice partner or owner. It is possible to have a good veterinary career without taking this path.

It is important to understand what is involved. Becoming a shareholder or buying out a business does not mean that you continue in the same job as a vet but with a better salary in exchange for your financial investment. Your role will change completely because you will be taking on the role of a business director in addition to your existing role as a vet (Figure 4). This means that time and energy must be spent on running the business. That is not to say you will need to spend time preparing the accounts, or payroll, or paying supplier invoices, because these tasks can and should be delegated to a support team or external service providers, but rather on making the key decisions that any business director must make.

The wider business decisions that are taken by owners include:

- Making major strategic choices: what specialisations should be added or abandoned, how many surgeries to run, with whom should you merge, which business should you buy and to whom should you sell?

- Managing a team: recruiting, paying, evaluating, motivating, supporting, training and helping your employees to grow as well as where necessary, resolving conflicts and letting some people go.

- Managing key functions such as defining know-how, enhancing services, defining pricing and purchasing policies.

- Managing major investments such as equipment and facilities.

As you can see, none of these decisions relates directly to veterinary medicine or surgery. Indeed, if you dedicate time to some or all of these issues, you will have a correspondingly smaller amount of time for actual veterinary practice and will therefore have to accept that a step back from this part of your career may be necessary.

- Do I understand clearly that to become an entrepreneur means greater financial and professional risks than those of a mere employee?

- Do I understand clearly that the vast majority of entrepreneurs work more hours and sacrifice more family time for their work than employees?

- Do I really like the fact that my work will have dimensions other than merely clinical? In other words, am I interested in and ready to lead personnel teams, to analyse my company’s finances, to design communication plans for my company’s clients, and to make hiring and firing decisions that will directly affect the team?

- Do I already have some experience in these dimensions?

- Have I acquired any kind of training that helps me supplement my clinical knowledge with other more business-related knowledge?

Finally

Finally, we should point out that regardless of the advice we have given, life is often about “taking” or not ”leaving” opportunities as they present themselves. Even if they are unexpected and their timing is less than ideal – and at that point, the decision is entirely yours to make (Figure 5).

Conclusion

n this Focus Special Edition, we have sought to provide the young veterinary surgeon with advice on how to get the best from their first years in their chosen profession, and guidance with the early decisions that will shape their veterinary future. A veterinary degree offers many opportunities, and you should take time to consider your options, explore different possibilities, and make careful career choices that are, ultimately, the right ones for you.Philippe Baralon

DVM, MBADr. Baralon graduated from the École Nationale Vétérinaire of Toulouse, France in 1984 and went on to study Economics (Master of Economics, Toulouse, 1985) and Business Administration (MBA, HEC-Paris 1990). He founded his own consulting group, Phylum, in 1990 and remains one of its partners to this day, acting primarily as a management consultant for veterinary practices in 30 countries worldwide. His main areas of specialization are strategy, marketing and finance, and he is also involved in training veterinarians and support staff in the field of practice management through lectures and workshop, as well as benchmarking the economics of veterinary medicine in different parts of the world. A prolific author, he has authored more than 50 articles on veterinary practice management.

Antje Blättner

DVMDr. Blaettner grew up in South Africa and Germany and graduated in 1988 after studying Veterinary Medicine in Berlin and Munich. She started and ran her own small animal practice before undertaking postgraduate training and coaching course at the University of Linz, Austria and then founded “Vetkom”. The company provides training to veterinarians and veterinary nurses in practice management in subjects such as customer communication, marketing and other management topics. Dr. Blaettner also is editor for two professional journals, “Teamkonkret” (for veterinary nurses) and “Veterinärspiegel” (for veterinarians).

Pere Mercader

DVM, MBA

Dr. Mercader established himself as a practice management consultant to veterinary clinics in 2001 and since then has developed this role in Spain, Portugal and some Latin-American countries. His main accomplishments include authoring profitability and pricing research studies involving Spanish veterinary clinics, lecturing on practice management in more than 30 countries, and authoring the textbook “Management Solutions for Veterinary Practices” which is published in Spanish, English and Chinese and has sold worldwide. In 2008, he co-founded VMS (Veterinary Management Studies), a business intelligence firm that provides a benchmarking service for more than 800 Spanish veterinary practices. Dr. Mercader was also a co-founder of the Spanish Veterinary Practice Management Association (AGESVET) and served on its board for eight years.

Mark Moran

MBAMark Moran has been a consultant to the veterinary profession for the last 19 years, providing business mentoring and support for veterinary clinic owners and key staff. His work involves helping veterinary practices create effective working environments, with happy staff, that meet the business owner’s values and expectations. He has a special interest in helping practices to improve their patient’s compliance to veterinary recommendations by making better use of data systems.

Other articles in this issue

Share on social media