Understanding the business (Part 1)

Written by Philippe Baralon , Antje Blättner , Pere Mercader and Mark Moran

Understanding the various factors involved that contribute to the income and expenditure of a veterinary clinic is key for long-term success. This chapter will give you the basics about the financial aspects of your work.

Key Points

To ensure that everyone knows the business strategy for a practice, its vision and mission statement should be clearly defined and openly shared with all staff.

It is important to define objectives for the practice for the coming year and choose the right KPIs (key performance indicators) to ensure a clinic develops and thrives.

Introduction

The fundamentals of running a business do not change whether that business is very small or an extremely large corporation. What changes is the formality of the processes that are involved. In a very small organisation such as a veterinary practice with a single owner and a few staff, the processes can exist in the mind of the owner and be communicated to the staff in an ad-hoc manner. Whereas, in a large company, the process of making decisions is more collective and the communication of information more complex, so the process has to be formalised to be effective.How to run a business

A bit of business background

Many veterinary owners are wary of introducing what they see as “big company” management into their clinics because of a suspicion that these methods were designed for use in enterprises where the primary goal is the creation of wealth for shareholders, and they see their business as being fundamentally different. However, vets are not unique in having a social conscience, and the strategic approach to business management now in use by many corporations takes account of the needs of other stakeholders such as the employees, the community it serves and the impact its activities have on the wider environment.

In this section, we set out a strategic approach which seeks to give business leaders a better understanding of how their companies are really doing regardless of the scale of their business, and which is appropriate for veterinary practices of all sizes. However, the implementation in very small veterinary practices may not need to be as formal as is being suggested.

Balancing conflicting goals

Where a business sets itself a wide range of aims rather than simply maximising profit, it is inevitable that some of the goals will appear to be in conflict. For example, a practice might state that “We will make ourselves accessible to our clients when they need us”, whilst also stating that “We will provide all staff with a healthy work-life balance”. The strategic approach that seeks to address these conflicts is often referred to as “Creating a Balanced Scorecard” after the work of Kaplan and Norton.

The Balanced Scorecard approach is ideally suited for use in veterinary businesses because veterinary owners often have wide-ranging goals and objectives. The approach needs to be adapted to reflect the size of the enterprise, and its scope restrained to reflect the level of management experience available. Practices that have adopted this approach achieve significant growth by developing their capability to respond to the needs of their clients and improving staff satisfaction, whilst meeting the social and financial goals set by the owners.

Implementing the Balanced Scorecard

The first stage is for the business owners to set out a clear vision for the practice in terms of what they want it to be, how they want it to be perceived, how they want it to impact on the other stakeholders and anything else that is important to them. The vision needs to be clear and succinct because it must be easy to communicate and simple to understand (Figure 1).

The main purpose of a mission statement is to communicate to all stakeholders the aspirations of the business owners, so that stakeholders can use these to inform their actions. Internally, this means that all staff will use the mission to guide their decisions and actions on a day-to- day level. In order to help them, the owners need to be clear about what they mean, and in particular give guidance on how to balance the sometimes conflicting goals. This can be achieved by providing additional detail, with day-to-day examples (Figure 1).

In simple terms, if we know where we want to be, what are the key things that we should try to achieve in the next year to make progress on our journey? The objectives we set will need to reflect the need to remain “balanced” and be realistic given the resources available (Box 1).

| Example: our objectives for the coming year |

|

Objective 1: to grow our practice We will do this by:

|

Step 4 – Identify the key levers to achieve our goals

The next stage is to identify the activities that you will need to start to do, do more of or less of to achieve your goals. These activities are the “levers” that you are going to “pull” in order to achieve a different outcome. Setting out the levers you have chosen in the headings suggested by Kaplan and Norton can help ensure that we have created a balanced set of key tasks and reduces the risk of creating unintended consequences (Table 1).

| Financial |

|

| Business processes |

|

| Customers |

|

| Learning and growth |

|

Step 5 – Developing the key measures

For each of our key activities, we need to identify one or more measures that will show we are making progress towards our goals and that can be used to stimulate the “Review and Learn” process. Ideally, we want to be able to track activity that leads to the outcome, not just the outcome itself. So, for example, if we plan to increase the take-up of preventative treatments and believe that we can do this by increasing the time we make available for our nurses to communicate healthcare messages to clients, then tracking the number of nurse consultations that take place could become a key indicator. In a similar way, if we plan to increase our use of digital communications then having staff asking clients for their e-mail address will be important, so measuring the percentage of active clients whose e-mail address is on record could become a key measure.

One or more measures need to be identified for each key action (Table 2).

| Activity | Key measure(s) |

| Improving our call handling | Monthly mystery shopping score |

| Promoting preventative healthcare at every interaction | Percent of active patients with vaccine status updated |

| Creating opportunities for staff to contribute ideas | Number of team meetings held Six-monthly staff survey results |

| Improve our capacity to inform clients about the value of specialised diets | Nurse consults for dietary advice Total diet sales Proportion of veterinary diets |

Step 6 – Reviewing and Learning from our progress

We need to review our progress on a regular (monthly) basis (Table 3). When reviewing measures, it is important that we make the process a positive experience. We did not plan to fail, and we employ good staff who aim to do a good job, so if outcomes are not as expected it is not that somebody has done something wrong, it is the process that has let us down.

| Objective | Key measure | |

| Controlling drug costs within agreed levels | Drug cost % of turnover | |

| Jan | 21% | |

| Feb | 20% | |

| March | 22% | |

| April | 21% | |

| May | 19% | |

| Comments | ||

|

Assess:

Plan:

|

||

When reviewing goals, we should have three questions in mind:

- Who can we praise? => We should look to praise at every opportunity. If the team did as they were asked, but the outcome was not achieved, we can still praise the effort.

- What have we just learned? => Whatever the outcome, good, bad or indifferent, it has shown us something. Identifying the Learning is key to making progress.

- What do we change? => What do we change and who do we tell to take the learning forward so that tomorrow is better than yesterday.

To sum up

A strategic business management process embraces every part of the practice. Its implementation needs to be carefully judged to match the existing practice culture. For practices that are already following some form of regular management process, and who have a culture of using and reviewing performance data, the Balanced Scorecard will represent a natural progression, and should be relatively easy to implement. However, experience has shown that for many practices its introduction requires a significant development of their existing managerial capability, and successful implementation will require a longer timetable and additional help and support for key staff.

Key indicators to understand the economics of a veterinary practice

| Typical key performance indicators | |

| a. Revenue quality indicator | a. Diagnostic ratio |

| b. Activity indicators | b.1. Active patients per full-time veterinary surgeon b.2. Daily transactions per full-time veterinary surgeon |

| c. Cost indicators | c.1. Practice payroll cost as a percentage of revenue c.2. Cost of every veterinary surgeon’s billable minute |

Veterinary practices generate revenue from three principal sources:

- Providing clinical services

- The re-sale of drugs and specialised products

- General pet shop sales and grooming

As a general rule, the veterinary surgeon has a significant influence on the first two which usually take place during a consultation or procedure, and so the total of these two is referred to as “medical revenue”. Pet shop and grooming revenue varies significantly between practices depending on their location and the space available, is less influenced by the veterinary surgeon and so is excluded from many ratios.

Key revenue indicators

1. Diagnostic ratio

This indicator is calculated by dividing the revenue generated by the veterinary practice in performing diagnostic tests such as external and internal lab tests, X-rays, ultrasound scans, endoscopies, electrocardiograms, MRIs, etc. by the total revenue from clinical services.

|

Revenue from diagnostic tests |

2. Average revenue per transaction

This indicator is calculated by dividing the total medical revenue by the number of transactions to obtain an average amount. Many practice management software systems calculate this indicator directly.

|

Average revenue per Total medical revenue |

Key activity indicators

1. Active patients per full-time veterinary surgeon

This indicator is obtained by dividing the number of patients seen at the clinic during a year by the number of full-time equivalent veterinary surgeons employed.

| Active patients Annual total patients seen per vet = ----------------------------------------- Full-time equivalent vets |

It is estimated that a full-time veterinary surgeon can provide a good quality service to between 750 and 1,100 patients annually. Figures outside of this range could be a clear warning sign regarding the size of the veterinary staff. A low figure indicating that veterinary surgeons are working in areas other than those that directly generate veterinary income, and a high figure suggesting that they have insufficient time with each patient.

2. Daily transactions per full-time veterinary surgeon

This indicator is obtained by dividing the number of medical transactions each year by the number of full-time veterinary surgeons times the number of days they work per year.

| Daily transactions Annual medical transactions per vet = ---------------------------------------------------- Full-time vets x number of days worked per year |

The goal is for veterinary surgeons to have an average of 10 to 12 medical transactions daily. So, in a country where veterinary surgeons work 250 days per year, we would expect them to achieve 2,500 to 3,000 transactions annually. If we assume that a patient will generate an average of about three medical transactions annually, then in most countries we need between 750 and 1,000 active patients per veterinary surgeon to generate this volume.

Key cost indicators

1. Payroll cost as percentage of revenue

In this calculation, we define a clinic’s “payroll cost” as the entire set of costs associated with remunerating its personnel, including partners. In addition to gross salaries, the total will include labour-related taxes at the company’s expense, and any fringe benefits or bonuses that make up the overall compensation received by the practice team such as private medical insurances or pensions.

| Payroll cost as Annual staff costs x 100 percentage of revenue = ----------------------------------------- Total revenue |

If a veterinary practice’s payroll cost clearly exceeds 40% of income, its economic feasibility begins to be at risk. However, figures significantly below this level may indicate that there is insufficient staff to provide a good service.

A typical error when estimating this indicator is the omission of a realistic market salary for the veterinary centre’s owners if they undertake clinical work in the business.

| Cost per billable Fixed annual costs of the clinic minute of a vet = ----------------------------------------- Sellable vet minutes per year |

To calculate the sellable veterinary surgeon minutes per year, we have to take into account the number of hours worked each day by every vet, the clinic’s opening hours and the number of days worked per year. Because it is impossible to sell every minute worked, as the vet will not be treating animals for every minute at work, and because some activities such as administration tasks cannot be billed, it is necessary to adjust the resulting figure using a so-called “efficiency factor”. For service professionals such as veterinary surgeons, it is estimated that on average we can hope to invoice clients for 65% of the available time.

|

Total annual costs of the clinic - purchases of supplies Cost per billable and merchandise |

For the practice to be viable, the charge per minute made for services must exceed this figure by an acceptable profit margin. If they do not, and it is not possible to raise prices, then efficiency savings must be found.

Understanding practice economics: why productivity is an issue

Let’s imagine we ask a young veterinary graduate:

“How much income would seem fair to you for your full-time work at a clinic?”.

Let’s also imagine that we receive the following answer:

“Considering the difficulty of my studies, the responsibility of the work I will carry out, the physical as well as intellectual effort I’ll have to deliver... I guess that about 2,500 Euros net per month would be a fair salary to start my career”.

This proposal, which is completely legitimate from the young veterinary surgeon’s point of view, may collide head-on with the economic principles of labour productivity.

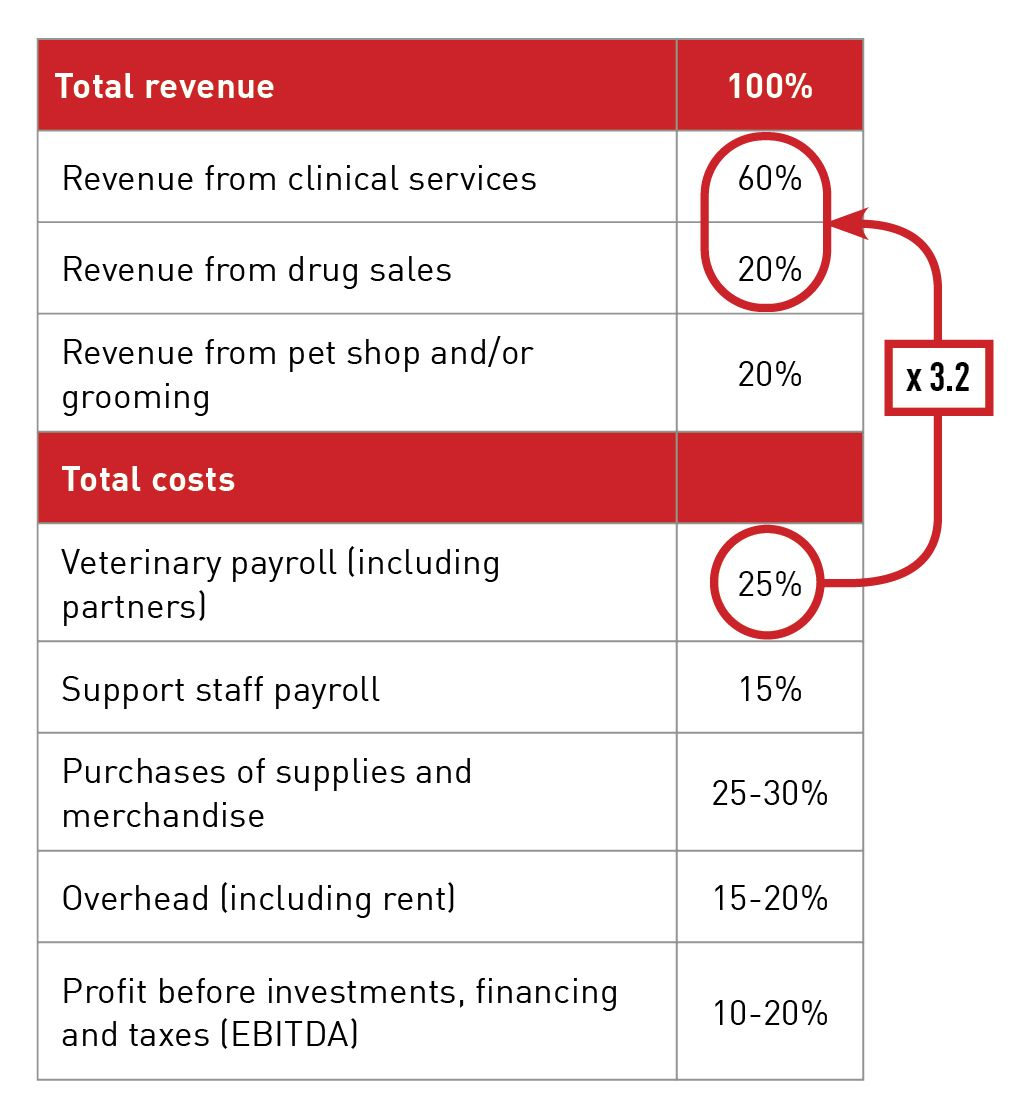

The following table shows a typical income statement (a yearly summary of revenue and expenses for a business) of many veterinary practices around the world (Table 5).

A major point from this table is that, in order for a veterinary practice to be economically sustainable (with an EBITDA between 10-20%), it is necessary that the labour cost of the veterinary surgeons should be around 25% of the centre’s income.

At the same time, we see how 80% of the centre’s income (in the form of clinical services and drug sales) is generated as a direct consequence of the veterinary surgeons’ activities.

Combining these two metrics (80/25 = 3.2), we can generate a ratio that will be very significant for the rest of our analysis:

Ratio 1

| Income generated by ➜ should be at minimum ➜ 3.2 times the full cost of a clinic's vets these vets |

The first problem that arises with this formula is of a practical nature: Most employees are not aware of their full payroll cost as individuals to their business – in other words, how much they are costing their company. An employee usually knows their net salary (what they take home) quite clearly, but may be less aware of the structure of their gross salary (what they take home, plus the taxes on their income that the state withholds before they receive their salary). However, what they almost never know is their total cost to their company, which is equal to their gross salary plus all labour-related taxes (which in most countries are designed to help finance the public health service, unemployment subsidies and retirement pensions). The magnitude of these costs may vary significantly from country to country, but they are clearly significant and in many countries they may end up representing a very significant portion of the labour cost carried by an employer.

Whilst the actual proportions will vary depending on the income tax rates and labour-related taxes in place in each country, ratio 2 shows a typical example:

| Net salary paid to employee | Gross salary earned before tax | Total payroll cost for the company |

| 1,000 € | 1,250 € | 1,550 € |

In this example, the actual labour cost for a veterinary practice is 1.55 times the net salary received by the employee.

If we now combine ratios 1 and 2, the result is:

| Income generated by ➜ should be at minimum ➜ 5 times the net salary a clinic's vets 3.2 x 1.55 = 5 received by these vets |

Suddenly, the hard reality of this so-called “Economic law of veterinary productivity” clashes with the young veterinary surgeon’s legitimate hopes of receiving a nice starting salary: To make it possible for the clinic to pay the desired net monthly €2,500, he or she must generate for the clinic at least €12,500 monthly, or €150,000 annually.

Given that these figures for salaries and income generation may seem either too high or too low depending on a particular country, Table 6 shows the calculations for different salary levels.

| Net salary of the young vet | Practice’s payroll cost | Income needed to be generated by the young vet |

| 1,000 € | 1,550 € | 5,000 € |

| 2,000 € | 3,100 € | 10,000 € |

|

2,500 € (our example) |

8,000 € (our example) |

12,500 € (our example) |

| 3,000 € | 4,650 € | 15,000 € |

| 4,000 € | 6,200 € | 20,000 € |

| 5,000 € | 7,750 € | 25,000 € |

At this point, the obvious question for the young veterinary surgeon will be: “How probable is it that I will be able to generate €150,000 annually so that the clinic can afford to pay me the net €2,500 I want to receive?”

The answer to this question will depend on a series of factors, not always under our young vet’s control:

- The practice caseload. Does the clinic have enough active patients so that each veterinary surgeon can reach a minimum of 12-15 transactions daily? If not, it will be difficult to achieve the required income figure.

- The practice’s pricing policy and discipline in collecting fees. Is all the work done adequately charged for? Is work discounted or even given free of charge on a discretionary basis? Because the lower the prices and higher the discounts, the more improbable it will be to reach the high-income figures needed to pay good salaries to qualified staff.

- Quality of the medicine offered at the practice. What proportion of medical acts carried out by the veterinary surgeon will be vaccines and consultations in comparison to other procedures with higher added value?

- The veterinary surgeon’s communication and persuasion skills. The veterinary surgeon who communicates clearly and persuasively ends up providing many more services, and as a consequence generating higher revenue for the practice.

Philippe Baralon

DVM, MBA

Dr. Baralon graduated from the École Nationale Vétérinaire of Toulouse, France in 1984 and went on to study Economics (Master of Economics, Toulouse, 1985) and Business Administration (MBA, HEC-Paris 1990). He founded his own consulting group, Phylum, in 1990 and remains one of its partners to this day, acting primarily as a management consultant for veterinary practices in 30 countries worldwide. His main areas of specialization are strategy, marketing and finance, and he is also involved in training veterinarians and support staff in the field of practice management through lectures and workshop, as well as benchmarking the economics of veterinary medicine in different parts of the world. A prolific author, he has authored more than 50 articles on veterinary practice management.

Antje Blättner

DVM

Dr. Blaettner grew up in South Africa and Germany and graduated in 1988 after studying Veterinary Medicine in Berlin and Munich. She started and ran her own small animal practice before undertaking postgraduate training and coaching course at the University of Linz, Austria and then founded “Vetkom”. The company provides training to veterinarians and veterinary nurses in practice management in subjects such as customer communication, marketing and other management topics. Dr. Blaettner also is editor for two professional journals, “Teamkonkret” (for veterinary nurses) and “Veterinärspiegel” (for veterinarians).

Pere Mercader

DVM, MBA

Dr. Mercader established himself as a practice management consultant to veterinary clinics in 2001 and since then has developed this role in Spain, Portugal and some Latin-American countries. His main accomplishments include authoring profitability and pricing research studies involving Spanish veterinary clinics, lecturing on practice management in more than 30 countries, and authoring the textbook “Management Solutions for Veterinary Practices” which is published in Spanish, English and Chinese and has sold worldwide. In 2008, he co-founded VMS (Veterinary Management Studies), a business intelligence firm that provides a benchmarking service for more than 800 Spanish veterinary practices. Dr. Mercader was also a co-founder of the Spanish Veterinary Practice Management Association (AGESVET) and served on its board for eight years.

Mark Moran

MBA

Mark Moran has been a consultant to the veterinary profession for the last 19 years, providing business mentoring and support for veterinary clinic owners and key staff. His work involves helping veterinary practices create effective working environments, with happy staff, that meet the business owner’s values and expectations. He has a special interest in helping practices to improve their patient’s compliance to veterinary recommendations by making better use of data systems.

Other articles in this issue

Share on social media