How I approach… Fractures of the maxilla and mandible in cats

Written by Markus Eickhoff

Jaw fractures account for 5-7% of all fractures in cats and are frequently caused by car accidents or by falls from a height. Jaw fractures are in many ways very different to fractures in other areas; in particular, there are differences in treatment options when a fractured section contains one or more teeth.

Article

Key points

The main focus when treating feline jaw fractures is to restore functional occlusion.

Jaw fractures are often only one component in a multiple trauma case.

Care must be taken to ensure that fracture treatment does not affect tooth viability.

Fracture assessment requires good radiographic technique and can be augmented by CT and MRI imaging.

Introduction

Jaw fractures account for 5-7% of all fractures in cats and are frequently caused by car accidents or by falls from a height (Figure 1). Jaw fractures are in many ways very different to fractures in other areas; in particular, there are differences in treatment options when a fractured section contains one or more teeth. Preserving tooth vitality and ensuring a natural occlusion are major factors during treatment; teeth can also have an important role in repositioning and stabilizing the fracture. Rapid, functional restoration is the most important consideration for treatment, as this is vital to permit the cat to feed properly. However, the fracture is often part of a multiple trauma problem and jaw reconstruction is not the first priority; typically stabilization of the animal and treatment for shock are of primary importance. In general a cat that has been involved in an accident is immediately taken to the veterinarian by its owner; however an injured animal may only return to the owner’s home some days after the trauma, and evidence of acute injury - and in particular a possible jaw fracture - may not be obvious.

Diagnosis

Abnormal movement of part of the jaw and crepitus are definitive indications of a fracture. Lack of symmetry, such as swelling, enophthalmos or exophthalmos, or lateral and rostro-caudal differences in jaw closing are not in themselves diagnostic of a fracture. If the jaw cannot close because the mandible is abnormally positioned, a fracture or a temporomandibular joint luxation may be present.

Fractures are usually identified by radiographs taken from several angles, i.e. dorsoventral/ventrodorsal and lateral views, as well as oblique projections to eliminate the superimposition of individual structures. Where there is a fracture of the maxilla, or if there is fracture of the caudal mandible, diagnosis may require radiography combined with 3D imaging (i.e. CT, MRI). If a fracture involves teeth it is helpful to obtain high-definition images of the fracture area using intra-oral radiographs.

Fractures and soft tissue injuries are often concomitant, such that there is bleeding in the mouth, increased salivation, and missing or displaced teeth, resulting in a painful, inflamed oral cavity which does not make for easy examination. The compact feline dentition means that even minor displacement of a tooth can lead to difficulty in closing the jaw; if this is noted the clinician should be alert for a potential fracture.

Fractures of the maxilla

If the maxilla is fractured, displacement is generally minimal; damage is most commonly noted in the area of the medial palatine suture. At the same time the fractured bones may be displaced vertically and/or horizontally, leading to an abnormal occlusion. Trauma frequently causes formation of a cleft palate, with the risk that food or foreign bodies may be aspirated. Stabilizing a fracture in this area is not always possible due to the mass of the structures involved. The best course of action, if possible, is to align and stabilize the bones using cerclage wire and an acrylic splint. To do this, wires are placed around the teeth, using a drill to position them as appropriate; the fracture is then reduced and stabilized, with the wires embedded in an acrylic splint which is then secured to the teeth. In many cases a splint by itself can be sufficient for stabilization.

- Bi-pedicle advancement technique: after debridement of the wound edges, bilateral para-marginal incisions are made a few millimeters palatinally to the premolars and molars. The entire area between the cleft palate and the paramarginal incision is undermined, together with the palatine artery, so that each flap is only connected rostrally and caudally to the palatine mucosa. When suturing the flaps in midline, a multi-layer - and thus secure – closure is desirable, and an absorbable synthetic membrane may be inserted under the mucosa to assist healing. Finally the lateral palatine incisions are closed with interrupted sutures.

- Overlapping flap technique: the prime aim of this technique is to ensure the sutures are supported by bone. On one side of the cleft palate a flap is prepared by a para-marginal incision while protecting the palatine artery, the edge of the cleft palate remaining untouched. The flap is then turned over (so that the roof of the mouth now forms the floor of the nasal cavity) and drawn across and under the palatine mucosa adjacent to the cleft palate before suturing it in place. This technique is problematic in cats as mobilization of the palatine artery can be difficult, but it is vital to preserve the vascular supply to the flap; if the artery is damaged or torn, necrosis of the flap is to be expected. Moreover, if the initial trauma causes laceration of the area around the cleft palate, there is a risk that a fistula may subsequently develop

.

Fractures of the mandible

The mandible consists of right and left hemimandibula, with a syndesmotic (ligamentous) or synchondrotic (cartilaginous) union at the symphysis. A synostosis (osseous union) may occur during a cat’s life, but generally slight movement remains between the two halves of the mandible. The mandible is differentiated into the horizontal ramus and the vertical ramus, the teeth being located in the alveolar bone of the horizontal ramus. Blood vessels and nerves enter the mandible via the mandibular foramen on the inside aspect of the vertical ramus and then run rostrally through the mandibular canal parallel to the ventral margin of the mandible, before reappearing again at the mental foramen at the level of the third premolar tooth. The mandible is connected to the base of the skull in the region of the temporal bone via the temporomandibular joint. The cat’s skull has a very deep fossa with pronounced caudal and rostral limitations, the retroarticular process and the post-glenoid process respectively. The temporomandibular joint is an incongruent hinge joint, separated by an intra-articular fibrocartilaginous disc into dorsal and ventral compartments, and is almost entirely limited to a single hinge movement, with very little lateral movement; this delivers the biting function which is ideal for the carnivorous feline dentition. The carnivorous function is completed by the anisognathous jaw, whereby the lower teeth are set closer together than the upper teeth.

The large masticatory muscles (masseter, pterygoideus and temporalis) insert on the lateral and medial surfaces of the vertical ramus proximal to the temporomandibular joint, and close the jaw; rostrally the digastricus and sublingual muscles open the jaw. The jaws are designed to cope with the demands of mastication, in that the trabeculae of the cancellous bone correspond to the lines of greatest tension, and the cortical thickness varies depending on the load bearing; the ventral border of the lower jaw, where there is a large compression load, is very thick.

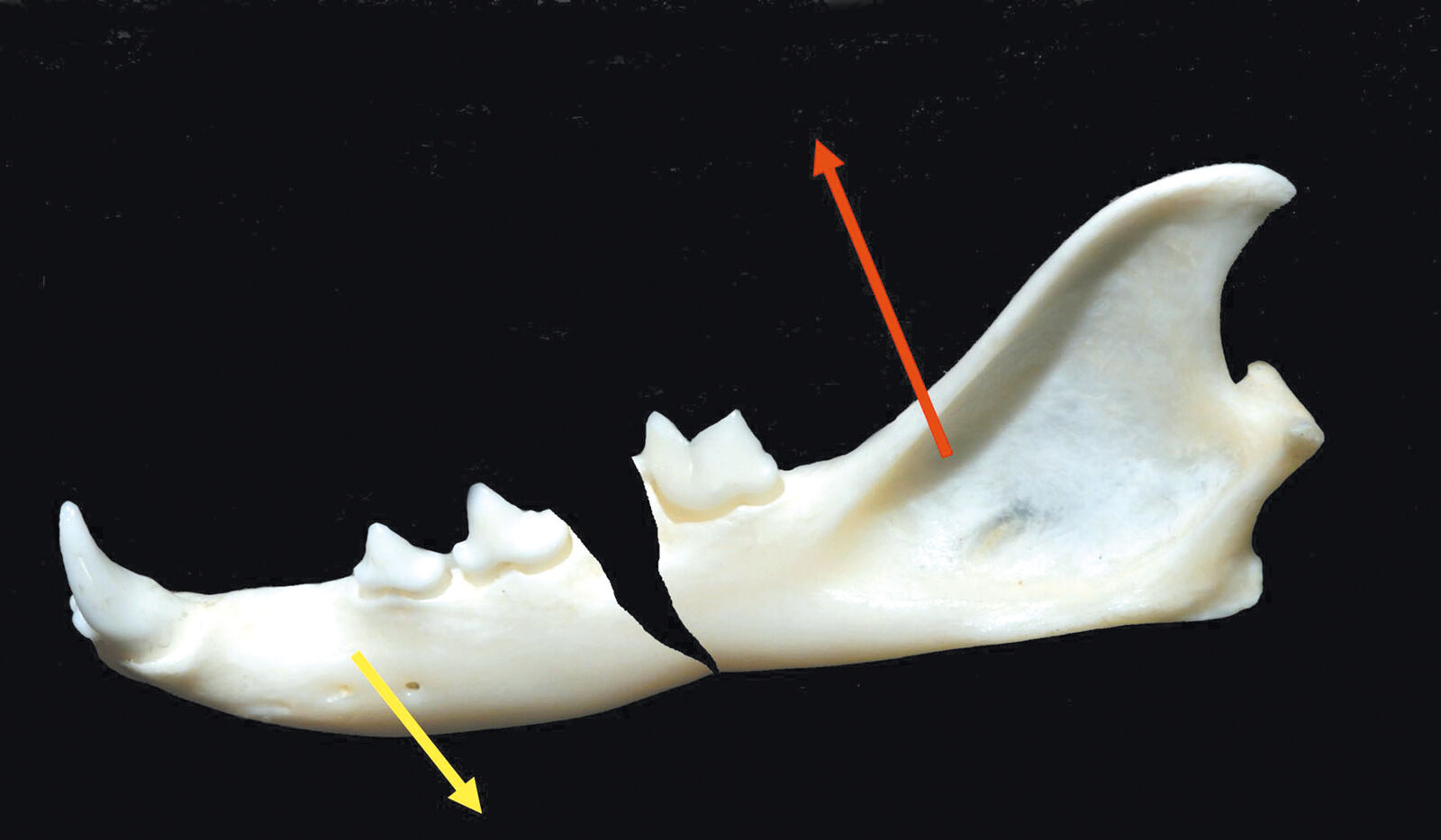

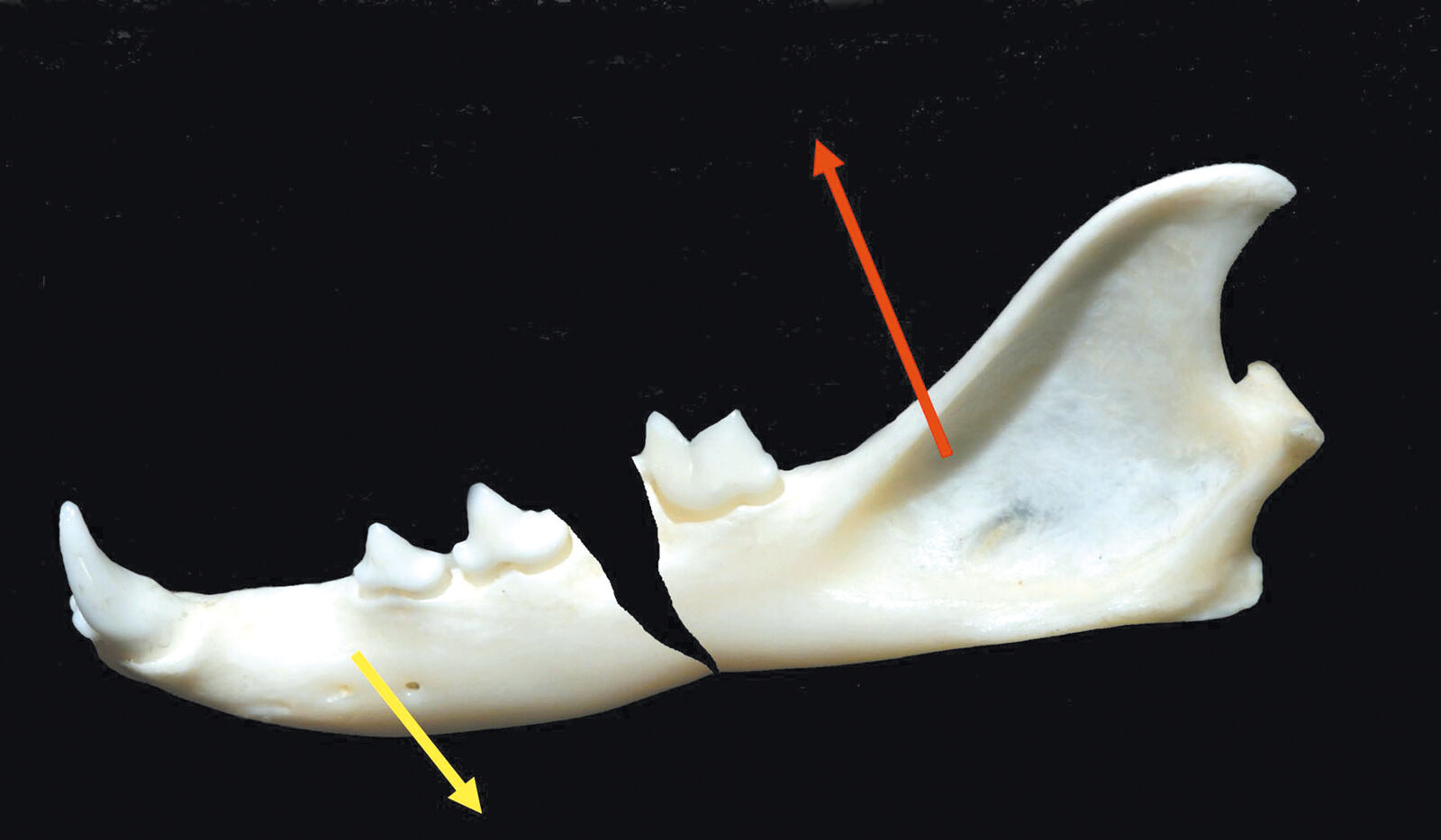

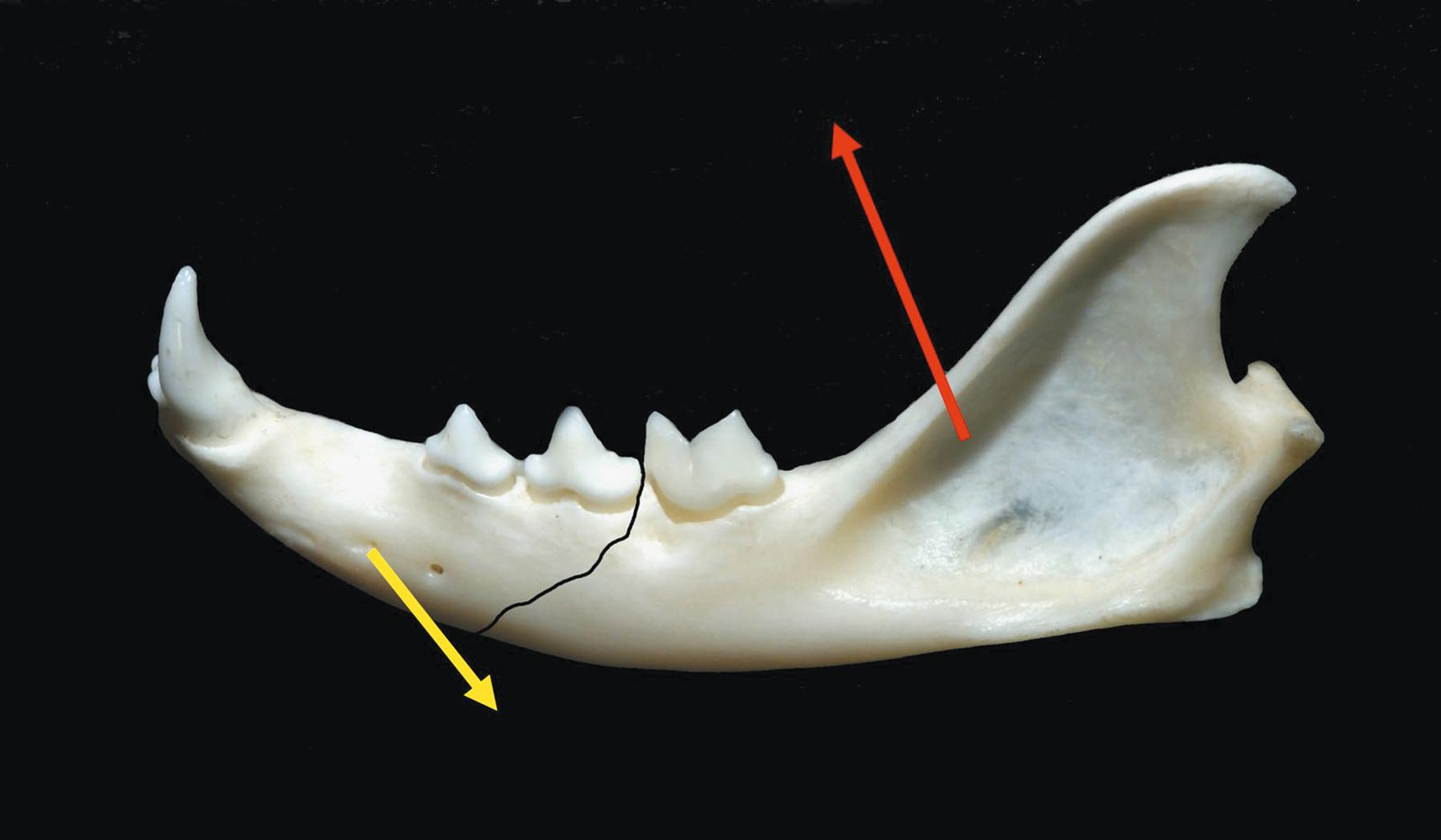

The pull of the masticatory muscles and the course of a fracture line can create either favorable or unfavorable conditions for fracture healing. Note that the ventral edge of the mandible corresponds to the compression load, whilst the alveolar crest is associated with the tensile load, so that fracture repair may utilize a neutralization technique on the ventral aspect, or tension banding on the dorsal aspect, or both. However the presence of teeth on the tensile side can make conventional internal fixation problematic, and a modified treatment approach is often necessary if the fracture site involves teeth.

For fractures of both maxilla and mandible it is desirable to assess dental occlusion when reducing the fracture. Rather than temporarily removing the endotracheal tube for assessment, I prefer to intubate the patient via a pharyngostomy, which allows repeated evaluation of alignment throughout surgery. This technique is also useful when dealing with fractures of the caudal section of the mandible, when fixation via temporary immobilization of the canine teeth may be desirable.

Care must be taken that placement of the wire does not cause the crowns of the lower canine teeth to converge, as this can lead to poor occlusion and may even prevent the jaw from closing. To prevent this, a composite bridge may be secured between the lower canines. Note that treatment of a symphyseal fracture using a bone screw or transverse pin is not recommended as this will damage the roots of the canine teeth.

Fracture of the horizontal mandible

As noted above, with a fracture of the mandibular body, depending on the course of the fracture line, the muscles may cause either a dislocation or a stabilization of the fracture; I refer to this as a unfavorable or favorable fracture accordingly. With a caudoventral fracture line, the pull of the musculature leads to distraction at the fracture gap (Figure 3a). With a caudodorsal fracture line the opposite happens – there is compression of the fracture gap (Figure 3b). If there are no teeth in the fractured section, the use of a bone plate (e.g. a miniplate) can be considered, but if teeth are present, the use of wire cerclage or a non-invasive method, such as an acrylic splint, is preferred. Note that when positioning the drill holes for wire placement one must take great care to avoid damaging tooth roots or the mandibular canal. The same problem arises when using a bone plate as the screw holes are pre-determined. On the ventral edge of the mandible, inserting a miniplate is relatively trouble-free but by itself it may not be sufficiently strong for the load-bearing required. Therefore where a fracture involves teeth that are subject to traction, stabilization should ensure that the teeth are protected, and rather than employ a bone plate, an alternative procedure such as an acrylic splint, wire cerclage or a combination of both is preferred.

With a favorable fracture line, dorsal cerclage can give sufficient stability; with an unfavorable line, two cerclage wires are essential (Figure 4a-d). Alternatively, non-invasive treatment using an acrylic splint attached to the tooth arcade is possible, alone or in combination with cerclage. Additional stabilization of the splint may be obtained using wires placed between the teeth. Note that some acrylics give off heat as they set, and cold-cure materials are to be preferred in order to prevent thermal damage to the teeth. Before the acrylic has set it is imperative to ensure that occlusion is optimal; the teeth should be etched with phosphoric acid to produce a retentive surface, as the carnivorous shape of the teeth does not predispose the acrylic to bond to the enamel.

Immobilization of the fracture area via an external dressing is usually very difficult due to the shape of the cat’s head, and use of either a tape muzzle or ligatures retained by buttons to reduce the fracture may not achieve total immobility, such that small movements at the fracture site remain; this can prevent bone healing and may lead to the creation of a pseudoarthrosis. If the oral cavity is fixed in a closed position for fracture repair, a feeding tube is obviously necessary.

Where there are multiple fragments or a large bone defect, the use of an external fixator can be considered, but again care should be taken to protect the teeth as much as possible. Two Kirschner wires per fragment are sufficient, inserted at different angles before aligning them close to the jaw and setting them in acrylic. Note that use of an intramedullary pin, e.g. placed in the mandibular canal is obsolete.

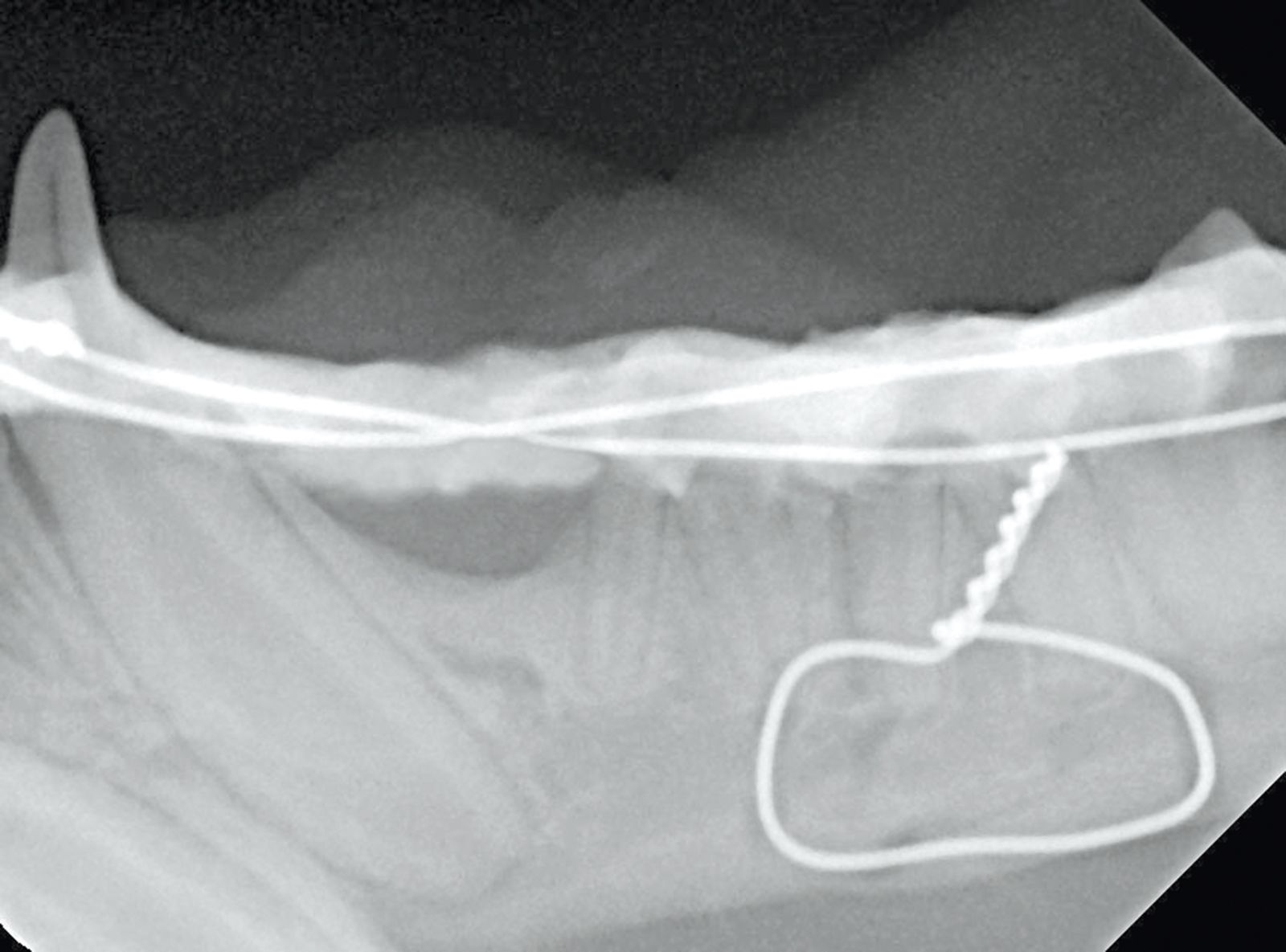

Fractures of the joint process may be identified clinically when the jaw cannot be closed on the damaged side. Fractures at this site are challenging in terms of radiographic diagnosis, and standard projections are frequently not sufficient to assess the fracture. With a lateral oblique projection it is possible to highlight the joint, but better still is a CT or MRI image. Because of the small anatomical size, a temporomandibular joint process fracture is very difficult or impossible to treat surgically, but the movement of the mandible can create a pseudoarthrosis. In many cases, despite the lack of healing, the pseudoarthrosis is sufficiently functional and no further treatment is required, as long as occlusion is not impeded. Callus formation can cause ankylosis of the joint, and resection of the temporomandibular joint head may be necessary. As direct treatment at the fracture site is usually not possible, there is the alternative of immobilizing the mandible via temporary fixation to the maxilla, a so-called inter-maxillary (or maxilla-mandibular) block, whereby the four canines are held in a fixed position by a composite bridge (Figure 5). Fixation with the mouth fully closed guarantees a good occlusion, but it is necessary to place an esophageal tube for feeding. Fixation in a semi-open position must be accurate in order to prevent subsequent poor occlusion, but in many cases will allow the patient independent intake of liquid food. As above, the use of a tape muzzle or ligatures to close the oral cavity when dealing with a temporomandibular joint fracture is, due to the obvious possibility of mandibular movement, very much a secondary preference.

The intermaxillary block should be kept in place for 2-3 weeks; this is usually sufficient for healing and prevents remodeling of the immobilized joint. The wire cerclages, plates and splints described above can be removed after six weeks.

Teeth in the fracture gap

In many cases teeth present within a fracture must be left in situ to guarantee stabilization or to enable an acrylic splint to be placed. Contraindications for leaving a tooth in the fracture area include an exacerbated periodontal event, a severe loosening of the tooth, or a clearly infected crack in the tooth. Where an essential tooth is fractured, temporary endodontic treatment is required to prevent pulpitis and to avoid impaired fracture healing. Definitive endodontic treatment can then be performed after the fracture has healed, or alternatively the tooth can be removed. Because the fracture gap is often in direct communication with the mouth and its associated bacteria, antibiotic treatment should be given in order to support healing, and anti-inflammatory and analgesic treatment is also obligatory.

Conclusion

The main focus when treating a feline jaw fracture is to restore functional occlusion; this is to be preferred to perfect alignment of the fracture fragments as judged by radiology. During treatment one should take care to protect the teeth as far as possible, as they are frequently needed for stabilizing the fracture, and although wire cerclage and osteosynthesis plates are very useful, non-invasive techniques using acrylic can often be very effective.Further reading

- Bellows J. Feline Dentistry: oral assessment, treatment and preventive care. 1st ed. Wiley: Blackwell 2010.

- Tutt C, Deeprose J,Crossley D. Eds. Manual of canine and feline dentistry. 3rd ed. Gloucester: BSAVA 2007.

- Eickhoff M. Zahn- Mund- und Kieferheilkunde bei Klein- und Heimtieren. 1st ed. Stuttgart: Enke Verlag 2005.

- Niemic BA. Small animal dental, oral and maxillofacial disease. 1st ed. London: Manson 2010.

- Verstraete FJM, Lommer MJ. Oral and maxillofacial surgery in dogs and cats. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Saunders 2012.

Markus Eickhoff

DVM, DMD

Germany

Dr. Eickhoff qualified as a dentist in 1993 from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe University in Frankfurt before graduating in 1999 as a veterinarian from Giessen’s Justus Liebig University. As a past president of the German Veterinary Dental Society, Dr. Eickhoff runs a veterinary practice dedicated to dental, oral and maxillofacial medicine and has authored three textbooks on the subject.

Other articles in this issue

Share on social media