Oral neoplasia

Written by Lassara McCartan and David Argyle

Oral cancer is frequently encountered in both feline and canine patients; dogs are more often affected than cats, with oral tumors accounting for 6% of canine cancers and 3% of feline cancers.

Key points

The most common oral tumors in dogs are malignant melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, fibrosarcoma and acanthomatous ameloblastoma.

The clinical stage, site and histological grade are prognostic for oral neoplasia, and therapeutic options rely on surgery and radiotherapy.

Aspiration of the draining mandibular lymph node and imaging of the thoracic cavity are both essential for proper work-up of oral tumors.

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common oral tumor of cats; these are challenging to treat and carry a grave prognosis.

Introduction

Oral cancer is frequently encountered in both feline and canine patients; dogs are more often affected than cats, with oral tumors accounting for 6% of canine cancers [1] and 3% of feline cancers [2]. The most common oral tumors in dogs are malignant melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, fibrosarcoma and acanthomatous ameloblastoma. In cats squamous cell carcinoma is by far the most commonly diagnosed oral tumor, followed by oral fibrosarcoma. This article aims to give a general overview of oral and oropharyngeal malignancies in the dog and cat, the common clinical signs associated with these tumors, their appropriate diagnostic work-up, and current therapeutic options and prognosis.Diagnostic approach and staging

The majority of cases will present with a noted oral mass; however oral lesions can often be missed by owners, especially if located caudally in the mouth.

Typical clinical signs include halitosis, increased salivation, dysphagia, loose teeth, weight loss, pain on opening the mouth and (less commonly) exophthalmos or facial asymmetry. No specific paraneoplastic conditions are associated with oral tumors.

The diagnostic work-up of any animal presenting with an oral mass should include a thorough history and physical examination, followed by determination of the diagnosis and staging. Diagnosis of oral tumors is typically via histopathology, requiring a wide incisional biopsy of the lesion under general anesthetic. Initially cytology samples can be undertaken, but oral lesions frequently have secondary inflammation, infection and necrosis, and cytology can often be non-diagnostic. Oral lesions typically have a vast blood supply and preparation for adequate hemostasis should be considered prior to biopsy. The use of electrocautery can distort the specimen and should only be used for hemostasis following blade incision or punch biopsy. To avoid seeding of tumor cells to normal skin, biopsy should always be taken from within the oral cavity and not via overlying dermis. Curative-intent resection for small lesions (especially those of the labial mucosa) may be considered at the time of initial work-up, but excisional biopsy of more extensive disease is not recommended [3].

The general anesthetic will - apart from facilitating biopsy - firstly allow a thorough oral examination. Close inspection of the pharynx, tonsils and hard palate should be undertaken, as well as the gross margins of the lesion itself. Secondly, oral radiographs or a computed tomography (CT) scan of the head should be undertaken to assess for microscopic disease extent. A CT scan allows for greater detail and can serve to analyze more precisely the location and extent of the mass as well as underlying bone lysis. Following advanced imaging, surgical resectability and discussion of best surgical approach, as well as likelihood of obtaining wide surgical margins, can be considered. Additionally contrast uptake in the draining lymph nodes can be assessed. CT also allows for radiotherapy treatment planning where surgical resection is not appropriate or is declined by the owner.

Further staging should routinely include aspiration of the draining mandibular lymph node if palpable (even if considered normal on palpation) and aspiration of the tonsils (should they appear grossly abnormal). Regional lymph nodes include the mandibular, parotid and medial retropharyngeal, however generally only the mandibular nodes are palpable. Thoracic cavity imaging is essential to assess for distant metastasis via either three-view thoracic radiographs or extension of the CT through the thoracic cavity.

The World Health Organization (WHO) clinical staging system for oral tumors can be applied to oral neoplasias in dogs (Table 1) and should be considered in each case, as the clinical stage of disease can be prognostic for oral tumors, especially for malignant melanoma.

| T : Primary tumor | |||

- T1a without bone invasion

- T1b with bone invasion

- T2a without bone invasion

- T2b with bone invasion

- T3a without bone invasion

- T3b with bone invasion

|

|||

| N: Regional lymph node | |||

- N1a no evidence of lymph node metastasis

- N1b evidence of lymph node metastasis

- N2a no evidence of lymph node metastasis

- N2b evidence of lymph node metastasis

|

|||

| M: Distant metastasis | |||

|

|||

|

Stage I

Stage II Stage III Stage IV |

T1 T2 T3 Any T Any T Any T |

N0, N1a, N2a N0, N1a, N2a N0, N1a, N2a N1b N2b, N3 Any N |

M0 M0 M0 M0 M0 M1 |

Oral malignancies are usually locally aggressive with a low to intermediate metastatic potential (apart from malignant melanoma). They typically occur in animals > 8 years old and all commonly cause bone lysis. Breeds at increased risk of developing oral tumors include the cocker spaniel, German shepherd dog, German shorthaired pointer, Weimaraner, golden retriever, Gordon setter, miniature poodle, chow chow and the boxer [3].

Surgery and radiotherapy are the mainstays of therapy for any oral tumor. The extent of the surgical approach will be dictated by the location and size of the lesion. In most cases bone resection will be necessary and this expectation should be outlined to the owners to allow for increased local tumor control. The functional and cosmetic outcome for most patients following mandibulectomy (segmental or hemi), maxillectomy (segmental) or orbitectomy is generally very good and owners satisfaction deemed to be high. With most oral tumors, 2 cm margins are required for consideration of reasonable local control; this can be very challenging in the case of caudally located tumors or tumors which breach the midline of the palate.

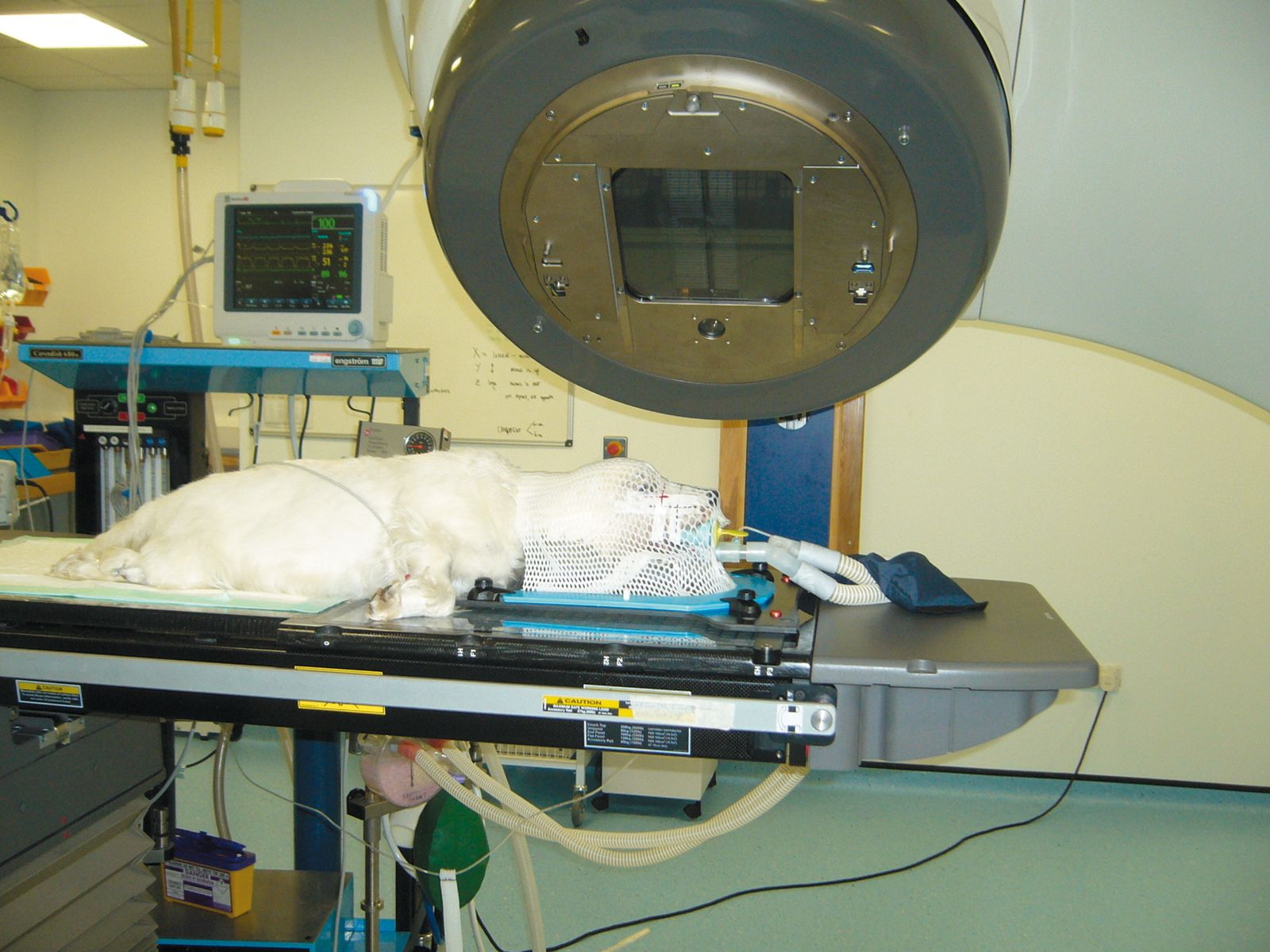

Radiotherapy can be instigated as a primary therapy, as a curative intent protocol or a palliative therapy, or as an adjunct to incomplete or marginal surgical excision of an oral tumor. Here consideration of the biological activity of the tumor type and estimation of the responsiveness of the tumor either in the gross disease or microscopic disease setting should be considered in order to determine an appropriate treatment protocol for each patient.

Canine oral tumors

These tumors are locally aggressive and have a high metastatic potential. The typical sites of metastasis include the regional lymph nodes (up to 74%) and the lungs (up to 67%). The WHO staging system for canine malignant melanoma is prognostic, with tumor size being of most relevance. The metastatic rate is size, site and stage dependent. Other poor prognostic factors include incomplete surgical margins, location (caudal mandible and rostral maxilla), mitotic index > 3, bone lysis [5], and (more recently documented) high ki-67 value protein levels on biopsy assay [6].

Surgery and radiotherapy both allow for generally excellent local tumor control. The concern in treating this neoplasm lies in the limitations of currently available viable systemic therapeutics and the fact that these patients die from distant metastatic disease.

Standard of care in a case where distant metastatic disease has not been documented is considered to be surgical resection of the mass with wide margins. Surgery is considered fast and financially acceptable in the majority of cases and can often carry a curative intent. Radiotherapy can be utilized in the case of incomplete/narrow surgical excision or instead of resection of the gross tumor where surgery is not deemed appropriate. Here hypo-fractionated protocols of 6-9 Gy weekly to a dose of 24-36 Gy have been utilized with excellent local control response rates.

Malignant melanoma is considered to be relatively resistant to chemotherapy. Platinum agents are used most frequently for both systemic control and/or radio-sensitization. Both carboplatin and melphalan have been outlined as potential agents, but documented overall response rates are < 30% [3].

The prognosis for dogs with malignant melanoma is poor. A stage I melanoma treated with standard therapies including surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy has a median survival time of 12-14 months, with most dogs dying from metastatic disease rather than local recurrence [5]. Because of this, ongoing investigation into systemic therapies to target secondary metastatic disease is required; immunotherapy is one such therapeutic potential, and in some countries a DNA vaccine is licensed for dogs with oral melanoma. The vaccine encodes for a human version of a protein called tyrosinase which is present on both human and canine melanoma cancer cells. Vaccination stimulates the dog to produce tyrosinase; the dog’s immune system subsequently generates a response towards the protein, which then attacks the tyrosinase present on the melanoma cells [7]. The vaccine is given intradermally every 2 weeks for a course of 4 treatments and then boostered every 6 months; although expensive, it has few side effects.

The over-expression of COX-2 in cutaneous, oral and ocular melanomas has led to the principle that NSAIDs may have a role to play in treating this malignancy [8]. Ongoing research is looking at the expression of KIT, a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor present in malignant melanoma, and its utilization as a target for novel anti-cancer therapeutics. The potential role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors for treatment of this tumor remains in the early stages.

For non-tonsillar SCC, as with any oral tumor, location and size is significant, and here the challenge is local tumor control. Despite a low metastatic potential full staging should be undertaken in these patients prior to definitive therapy. Local tumor can be controlled with surgery or radiotherapy, and in many cases it is considered ideal to use a combination of both. Outcome is better for mandibular lesions rather than lesions of the maxilla. Following mandibulectomy a recurrence rate of 8% was reported when a minimum margin of 1 cm was achieved, with a 91% one-year survival rate and median survival time between 19-26 months. Following maxillectomy local recurrence rates were 29%, with a 57% one-year survival rate and median survival time of 10-19 months [10]. A 2 cm surgical margin is recommended for SCC removal. If surgery is not feasible (due to size or location), or where surgical margins are incomplete or narrow, definitive radiation therapy is appropriate. Various studies have looked at survival time following radiation treatment; in one study of 19 dogs treated with full course radiotherapy the overall progression-free survival time was 36 months, and here local tumor recurrence, rather than regional metastatic development, was the typical reason for treatment failure, and another report recorded a median disease-free interval and survival of 12 and 14 months respectively for dogs treated with full course radiotherapy [10]. Local tumor control is improved with smaller tumors, those located rostrally, on the mandible and in patients that are younger in age.

Chemotherapy is not typically indicated for oral SCC, but may be utilized in dogs with identified metastatic disease, those with a heavy tumor burden, or where owners decline surgery and/or radiotherapy. Here consideration of a platinum agent is appropriate. NSAIDs are a reasonable adjunctive in standard of care options, along with chemotherapy or as a stand-alone therapy, where more aggressive therapeutics have been declined.

With a generally recognized low metastatic rate the role of chemotherapy here has not been fully identified and the focus should remain on local disease control.

Canine acanthomatous ameloblastoma (CAA) is characterized as a benign odontogenic tumor or epulis. The term epulis is a descriptive term applied to expansile gingival lesions. Odontogenic tumors are generally considered rare and there has been much confusion regarding their nomenclature and origin as well as other reactive lesions of the gingiva. The acanthomatous epulis has microscopic features in common with human ameloblastoma. However its clinically invasive nature, commonly with destruction of underlying bone (unlike other odontogenic tumors) is similar to the human intra-osseous ameloblastoma. The tumor is now termed CAA because it is considered its own entity with no precise human equivalent [12].

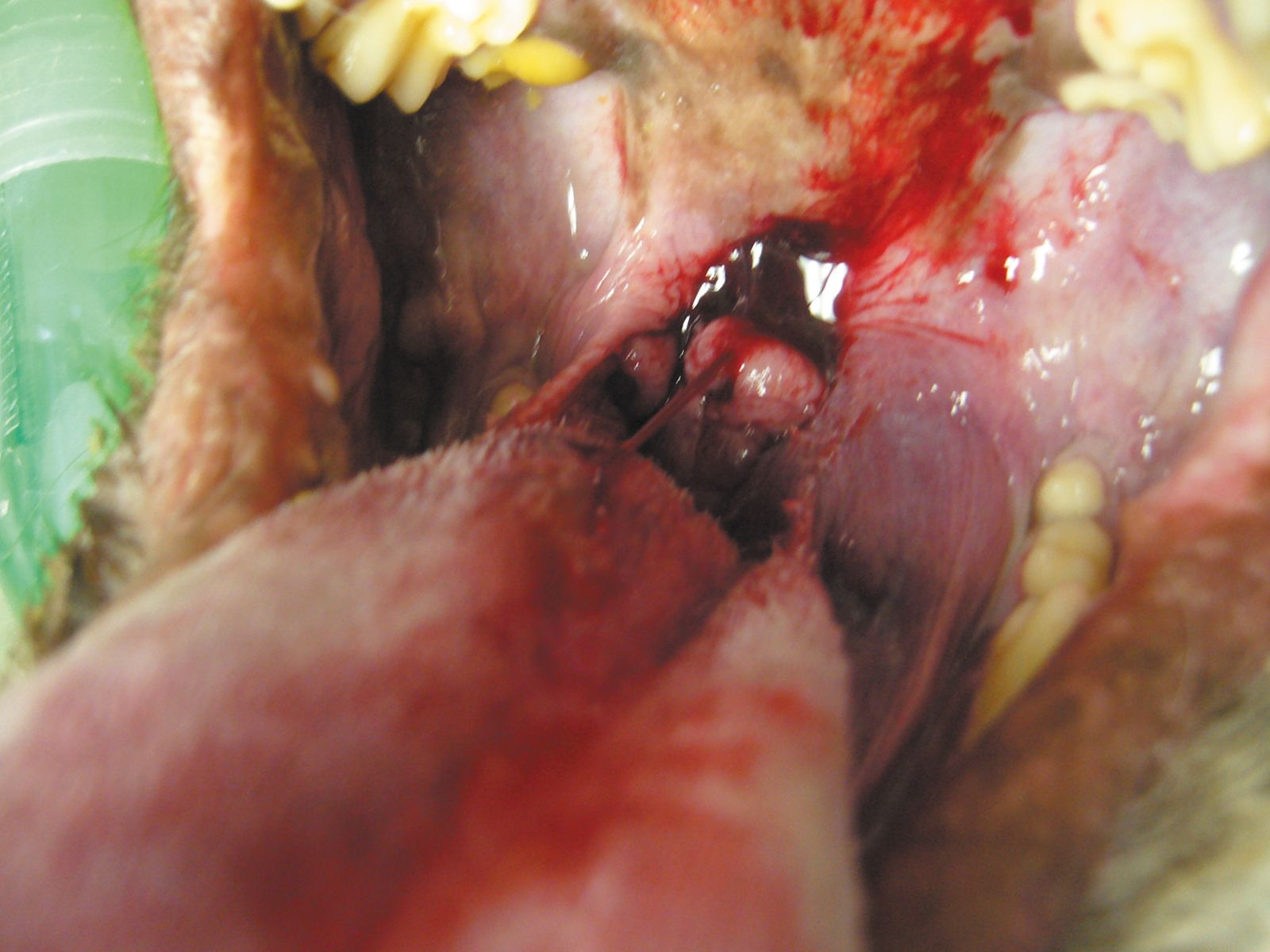

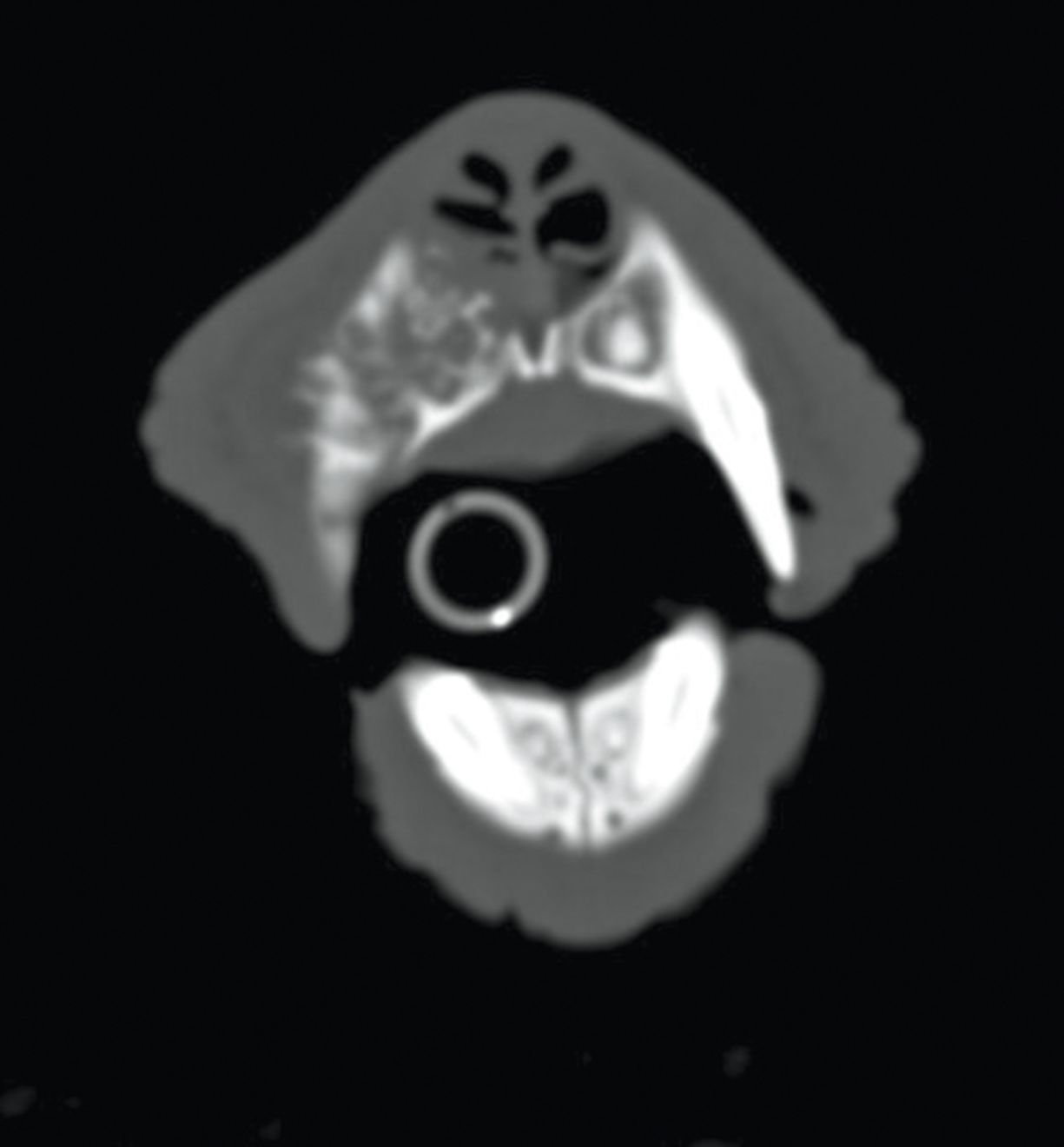

CAA most commonly affects the rostral mandible, and golden retrievers, akitas, cocker spaniels and Shetland sheepdogs are over-represented breeds [3] [12]. The typical appearance is cauliflower-like, red and ulcerated (Figure 3). While considered locally aggressive, the tumors have not been known to metastasize and hence local control is the mainstay of therapy. Surgery to include mandibulectomy or maxillectomy is usually employed and local recurrence rates with wide excision are low. A CT scan to determine the exact extent of underlying bone involvement is advantageous (Figure 4). Definitive radiation therapy can also be employed where wide surgical margins are deemed unlikely or in order to preserve function or cosmesis. Radiation has been found to have excellent response rates with local recurrence rates (up to 18%) reported; recurrence is more likely in larger tumors [13]. Intra-lesional bleomycin is another option that has been described for CAA treatment [14].

The prognosis with this tumor type is excellent and, for most patients, eventual death is unrelated to the odontogenic tumor.

A recent publication has described a less aggressive surgical rim excision for the treatment of this tumor type. Here the ventral cortical bone of the mandible or dorsal portion of the maxilla is left intact while the tumor, surrounding teeth and periodontal structures are removed. Obvious advantages include decreased mandibular drift and improved dental occlusion. In 9 cases that had follow-up from 3 months to 5 years no recurrence was recorded and high client satisfaction was documented [15]. The lesions selected for such surgical intervention were small (< 2 cm) and had bone involvement of < 3 mm, which may indicate that wide traditional excision should continue to be appropriate for larger lesions.

Feline oral tumors

Squamous cell carcinoma

This is the most common oral tumor of cats, accounting for approximately 65% of oral tumors seen. It can arise from any oral mucosal surface, including the sublingual region, the tonsils and the pharynx. The tumor is very locally aggressive and commonly causes underlying bone lysis. The regional lymph node and distant metastatic rate is low and estimated at 10%. Epidemiological studies suggest that various risk factors may predispose to the development of SCC but no prospective, controlled studies have yet been undertaken to further advance this possibility [16]. The average age of cats affected is 10-12 years; any oral lesion in an older cat should be biopsied promptly as early diagnosis may improve the prognosis. Many cats will present because the owners have noted an oral mass and the most common clinical signs include ptyalism, halitosis and, in some cases, dysphagia. Staging should be as for canine oral tumor and include cytology of the regional mandibular lymph node and three-view thoracic radiographs. While oral radiographs can be helpful - and may be reasonable - to determine underlying bone lysis, CT imaging allows for greater accuracy in assessing bone involvement and should be undertaken in all cases where aggressive therapy is being considered.

SCC remains very challenging to treat and carries a grave prognosis. While surgery and radiation therapy can be undertaken, the median survival time is short, with survival times > 3 months uncommon and a one-year survival rate < 10%. However the prognosis is potentially improved for those patients with small and rostrally located lesions where wide surgical excision can be undertaken and/or adjuvant radiotherapy employed. Resection of the mandible plus curative intent radiotherapy gives a median survival of 14 months. In the majority of cases surgery alone does not offer a significantly extended survival time as the disease is so locally invasive and wide margins are typically unachievable. Likewise palliative radiotherapy is not proven to improve survival significantly over untreated cases. No chemotherapy to date has been shown to be effective as treatment. Historically results were improved with the combination of radiotherapy and radiation sensitizers, but rapid recurrence was documented. A recent paper has described an accelerated radiation protocol with concurrent chemotherapy; cats received 14 fractions of 3.5 Gy for a total of 49 Gy in a nine-day period while receiving concurrent intravenous carboplatin. The protocol was intense but well-tolerated with a median survival time of 169 days; cats with disease of the tonsils or cheek had an increased survival time [17].

Pain management and the consideration of NSAIDs and antibiotic therapy, as well as frequent quality of life assessments, are crucial in the medical management of these cases.

Conclusion

The etiology of oral cancer in dogs and cats is poorly documented. Comparatively the most common oral cancer in humans, SCC is associated with alcohol and tobacco use. Similarly here the clinical stage, site and histological grade are prognostic and therapeutic options rely on surgery and radiotherapy. The initial diagnostic work-up of oral tumors in dogs and cats is crucial to determine the definitive diagnosis, clinical staging and appropriate therapeutic options, as well as the prognosis in each case. With the exception of malignant melanoma, local disease control is typically the main aim for the most common tumors. Recent advancements and refinement of our ability to deliver radiotherapy (Figure 5) to veterinary patients should result in its increased utilization in the treatment of these tumors and as part of a multimodality therapeutic approach using both surgery and chemotherapy where appropriate.

References

- Hoyt RF, Withrow SJ, Hoyt RF, et al. Oral malignancy in the dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1984;20:83-92.

- Grier CK, Mayer MN. Radiation therapy of canine nontonsillar squamous cell carcinoma. Can Vet J - Revue Vétérinaire Canadienne 2007;48(11):1189-91.

- Frazier SA, Johns SM, Ortega J, et al. Outcome in dogs with surgically resected oral fibrosarcoma (1997-2008). Vet Comp Oncol 2012;10(1):33-43.

- Fiani N, Verstraete FJM, Kass PH, et al. Clinicopathologic characterization of odontogenic tumors and focal fibrous hyperplasia in dogs: 152 cases (1995-2005). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2011;238(4):495-500.

- Mayer MN, Anthony JM. Radiation therapy for oral tumors: Canine acanthomatous ameloblastoma. Can Vet J - Revue Vétérinaire Canadienne. 2007;48(1):99-101.

- Kelly JM, Belding BA, Schaefer AK. Acanthomatous ameloblastoma in dogs treated with intralesional bleomycin. Vet Comp Oncol 2010;8(2):81-6.

- Murray RL, Aitken ML, Gottfried SD. The use of rim excision as a treatment for canine acanthomatous ameloblastoma. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2010;46(2): 91-6.

- Moore A. Treatment choices for oral cancer in cats; What is possible? What is reasonable? J Fel Med Surg 2009;11(1):23-31.

- Fidel J, Lyons J, Tripp C, et al. Treatment of oral squamous cell carcinoma with accelerated radiation therapy and concomitant carboplatin in cats. J Vet Int Med 2011;25(3):504-10.

- Stebbins KE, Morse CC, Goldschmidt MH. Feline oral neoplasia: a ten-year survey. Vet Pathol 1989;26:121-8.

- Liptak JM, Withrow SJ. Oral Tumors. In: Withrow, SJ and Vail, DM eds. Small Animal Clinical Oncology 4th ed. St Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:455-510.

- Ramos-Vara JA, Beissenherz ME, Miller MA, et al. Retrospective study of 338 canine oral melanomas with clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical review of 129 cases. Vet Pathol 2000;37(6):597-608.

- Bergman PJ. Canine oral melanoma. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2007;22(2): 55-60.

- Bergin IL, Smedley RC, Esplin DG, et al. Prognostic evaluation of Ki67 threshold value in canine oral melanoma. Vet Pathol 2011;48(1):41-53.

- USDA licenses DNA vaccine for treatment of melanoma in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2010;236(5):495.

- Pires I, Garcia A, Prada J, et al. COX-1 and COX-2 expression in canine cutaneous, oral and ocular melanocytic tumors. J Comp Pathol 2010;143(2- 3):142-9.

- Clarke BS, Mannion PA, White RAS. Rib metastases from a non-tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma in a dog. J Small Anim Pract 2011;52(3):163-7. 10.

Lassara McCartan

MVB, MRCVS

Dr. McCartan graduated from University College Dublin in 2006 and spent more than two years in small animal and equine private practice before undertaking an oncology internship at the University of Wisconsin - Madison. She then remained in Madison to begin the first half of her oncology residency training, which she is currently completing at Edinburgh. She has a special interest in new anticancer therapeutics as well as maintaining excellent quality of life in veterinary oncology patients.

David Argyle

BVMS, PhD, Dip. ECVIM-CA (Oncology), MRCVS

Dr. Argyle graduated from the University of Glasgow and after a period in practice returned to Glasgow to complete a PhD in Oncology/Immunology. He was senior lecturer in clinical oncology at Glasgow until 2002 when he became head of veterinary oncology at the University of Wisconsin. In 2005 he returned to Edinburgh University to the William Dick Chair of Veterinary Clinical Studies and became the dean for international and postgraduate research for both medicine and veterinary medicine in 2009. He is currently Head of School and Dean for the veterinary college. He is an RCVS/European specialist in Veterinary Oncology, and co-scientific editor of the Journal of Veterinary and Comparative Oncology. His major research interests are cancer and stem cell biology.

Other articles in this issue

Share on social media