Wound management 2 – Penetrating injuries in dogs

Written by Bonnie Campbell

Penetrating wounds are often deceiving! An innocuous-looking skin puncture may overlie tissue that has been significantly compromised by strong forces, vascular damage, and/or inoculation of bacteria or foreign material.

Article

Key points

When presented with a bite or bullet wound case, think “iceberg”: a small amount of surface damage often belies a large amount of damage in the deeper tissues!

Endoscopy allows early detection of esophageal perforations before clinical signs appear.

Penetrating wounds should be opened, explored, debrided, and lavaged; they are usually then best managed as open wounds. If wounds require closure, they should be closed over a drain.

If there is a penetrating wound (or suspicion thereof) or significant crush injury to the abdomen, exploratory celiotomy is indicated.

Foreign objects lodged in the body are best removed via a surgical approach in an operating theatre with an anesthetized, fully prepared patient.

Introduction

Penetrating wounds are often deceiving! An innocuous-looking skin puncture may overlie tissue that has been significantly compromised by strong forces, vascular damage, and/or inoculation of bacteria or foreign material. Even if the animal appears stable initially, continuing deterioration of damaged tissue can lead to necrosis, infection, inflammation, sepsis and death. Effective management of penetrating wounds requires first and foremost that the clinician recognizes small wounds can hide severe damage.Forces and tissue damage

A dog bite can generate over 450 psi (pounds per square inch) of force [1], causing both direct and collateral damage to tissues. When the attacker’s canine teeth penetrate the skin and the attacker shakes its head, the elasticity of skin allows it to move along with the teeth, so only puncture holes are made in the skin. Subdermally, however, the teeth shear through a wide area of less mobile tissue, avulsing skin from muscle, tearing soft tissue and neurovascular structures, creating dead space, and inoculating bacteria and foreign material. All of this injury is further compounded by the crushing forces exerted by the premolars and molars.

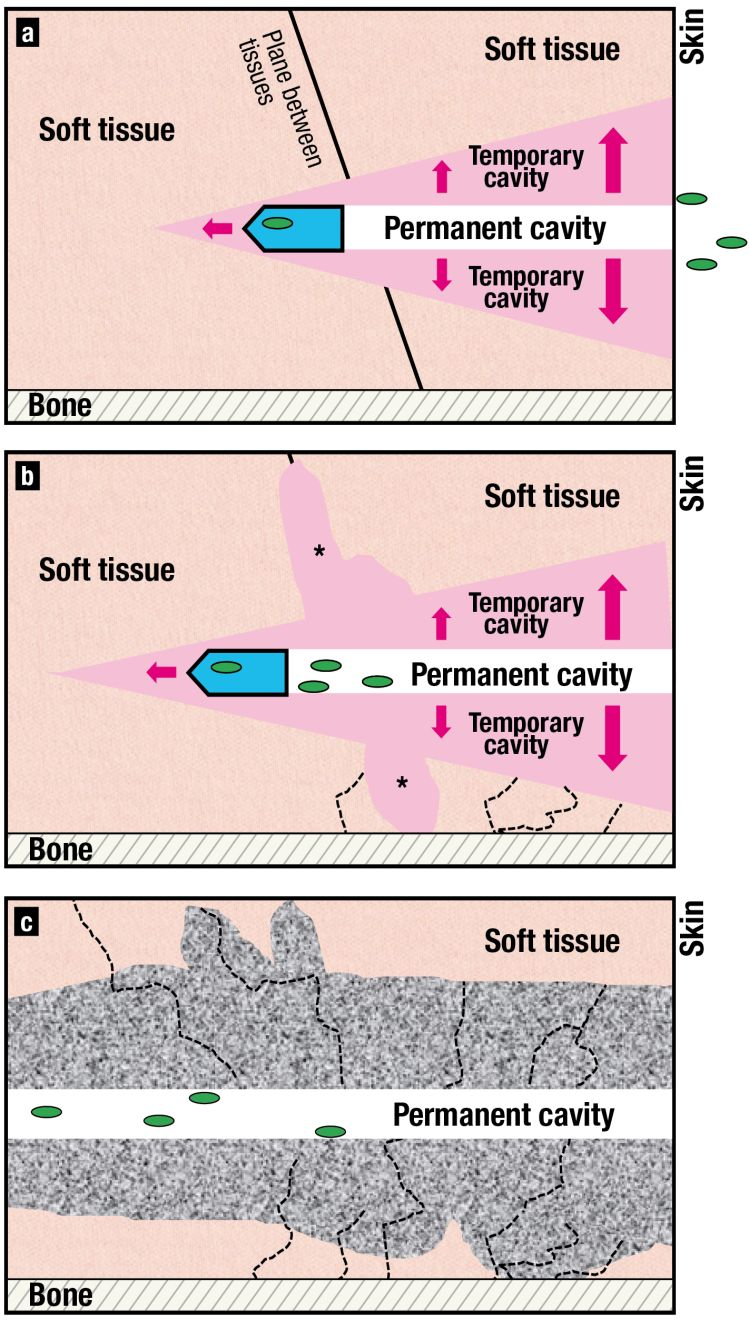

Like bites, bullets cause both direct and collateral damage (Figure 1), imparting energy proportional to their mass and velocity [Kinetic Energy = ½ x mass x velocity2]. Dense tissues (e.g., liver, spleen,bone) absorb more energy than less dense, more elastic tissues (e.g., muscle and lung), which explains why cortical bone hit by a bullet may shatter into multiple pieces (each of which becomes a new projectile) while an identical bullet with the same energy can pass cleanly through a lung lobe. Cavitation – the pressure wave created by a projectile – can mean that a bullet may fracture bones, tear vessels, rupture bowel, and contuse organs that the missile never contacts directly.

The term “iceberg effect” can be used to describe bite and bullet wounds, because the small amount of damage seen on the skin often belies a large amount of damage underneath. In subdermal tissues, necrosis, hematomas, compromised vasculature, dead space, inoculated bacteria, and foreign material stimulate local inflammatory, immunologic, coagulation, and fibrinolytic cascades. With insufficient treatment, these cascades may overwhelm the body’s controls, resulting in systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) or sepsis (SIRS + infection) [2] [3] [4]. Patients can appear stable even as the body is ramping up to SIRS, and then acutely decompensate several days after injury. The clinician needs to think about the iceberg effect from the start and be proactive to stop progression to SIRS.

Other penetrating injuries can occur from sticks (e.g., when playing “fetch”, running into a stick in the field) or other environmental objects. The amount of energy imparted depends on mass and velocity (of the object or the dog, whichever is moving), and the iceberg effect occurs due to the blunt trauma associated with objects that are not aerodynamic.

Patient assessment

Surgical management

Surgical exploration is needed to fully assess the extent of trauma caused by penetrating injuries [2] [3] [7]. Furthermore, thorough debridement of devitalized, contaminated tissue is the only effective way to prevent or treat SIRS or sepsis. Thus, penetrating wounds should be opened, explored, debrided, and lavaged early on [2] [3]. If the damage ended directly below the skin, the surgery has been minor. If the damage continued into deeper tissue and/or if foreign material was lodged inside, surgery can prevent considerable morbidity and even mortality.

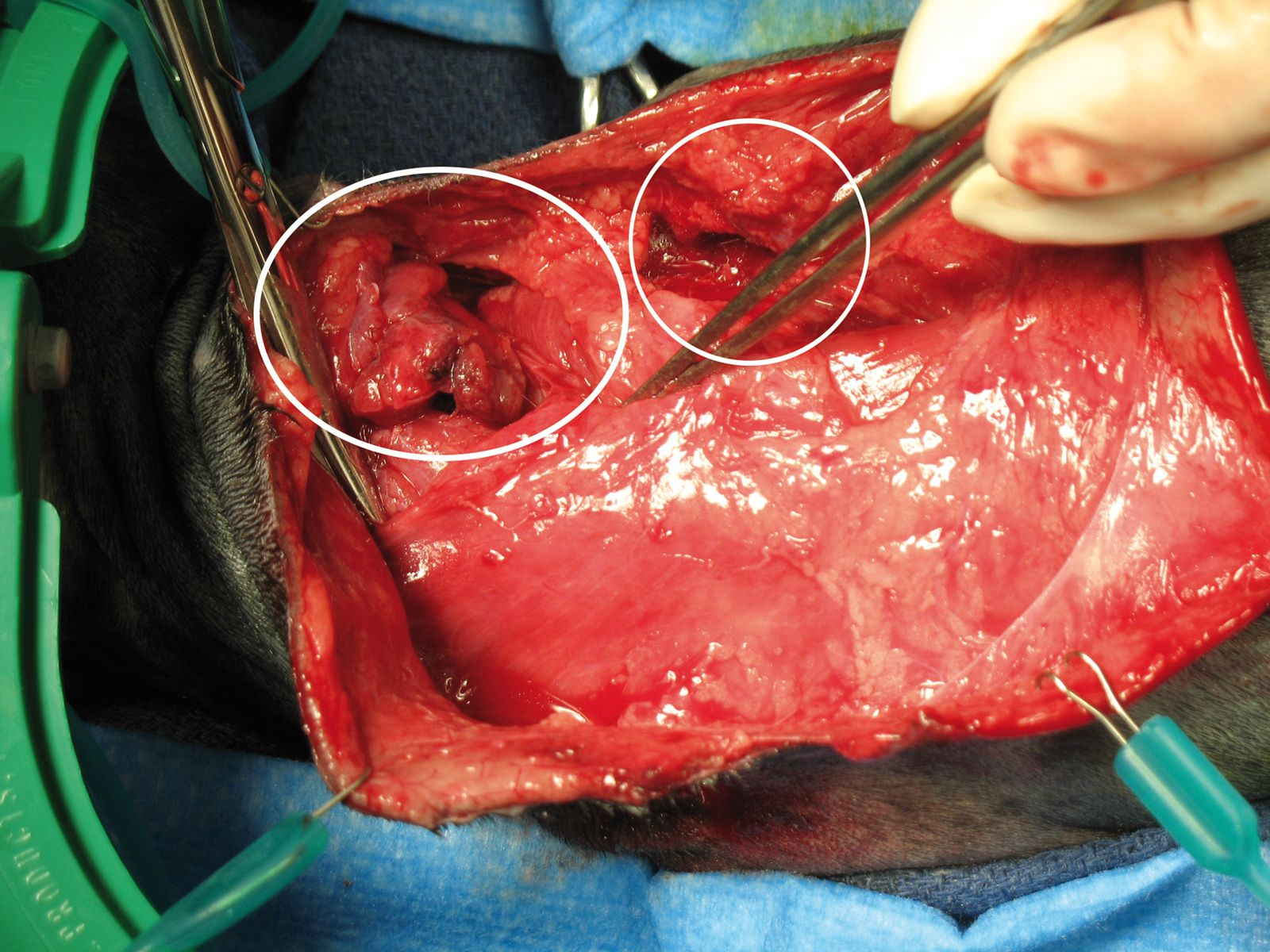

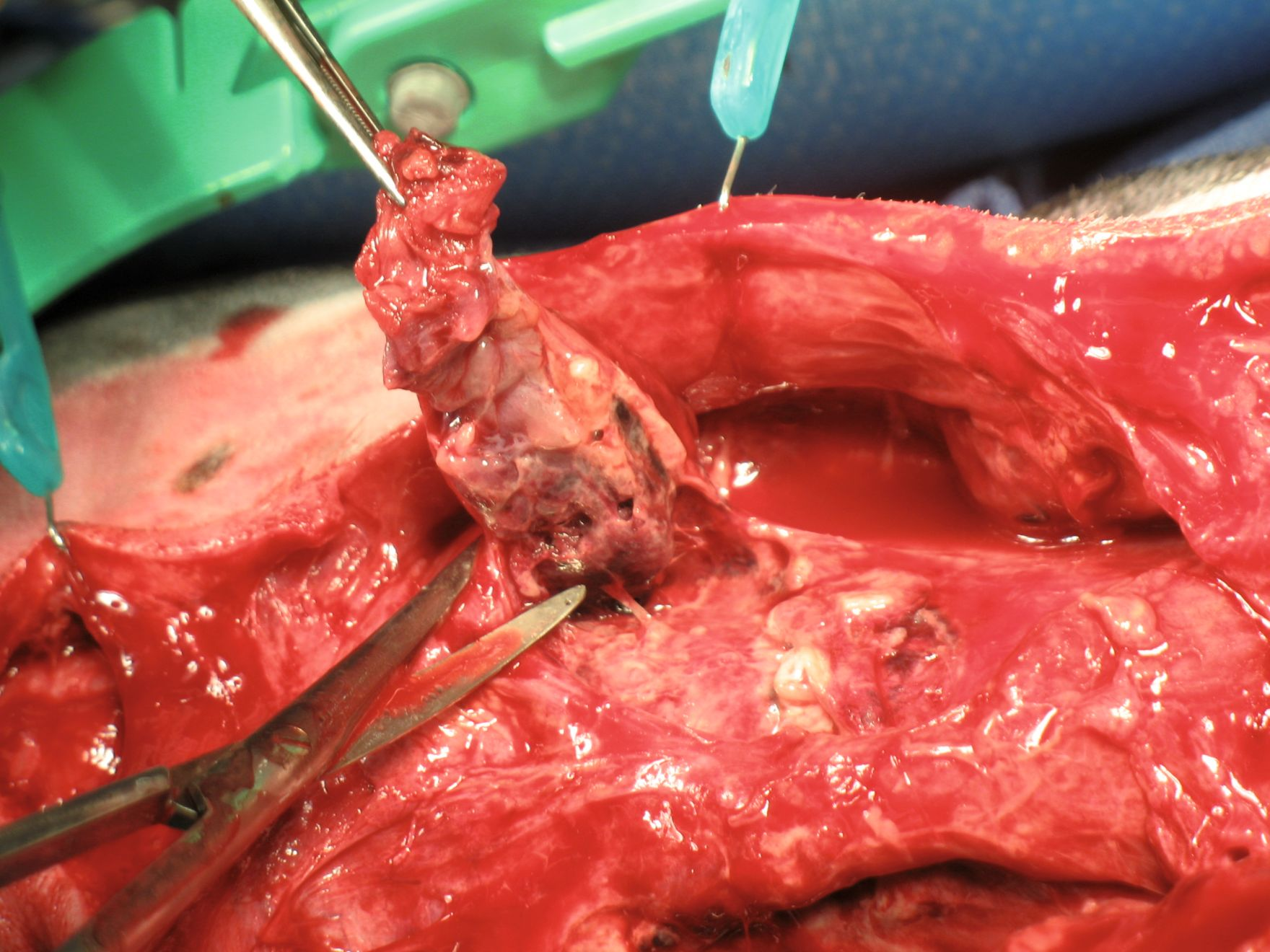

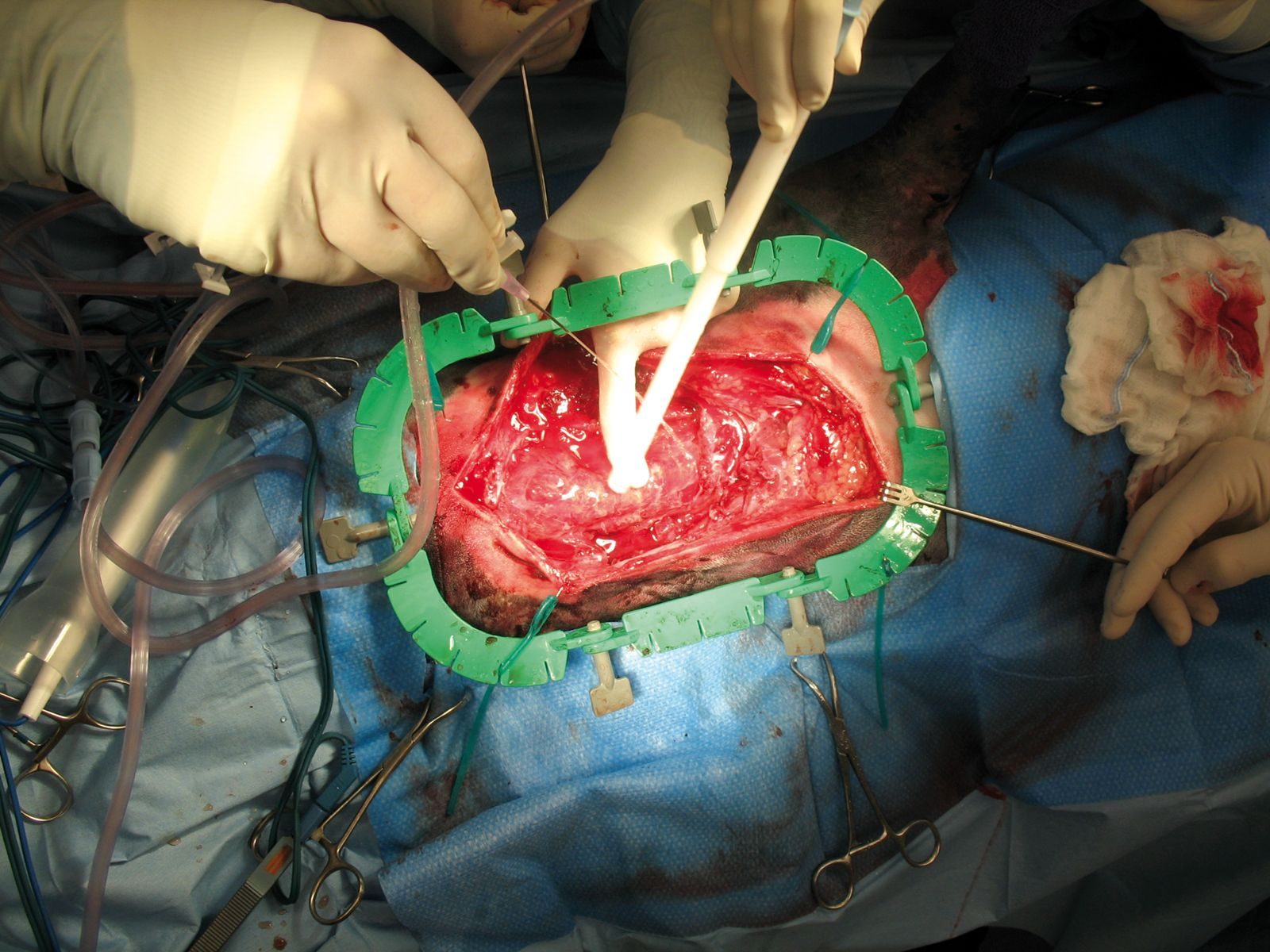

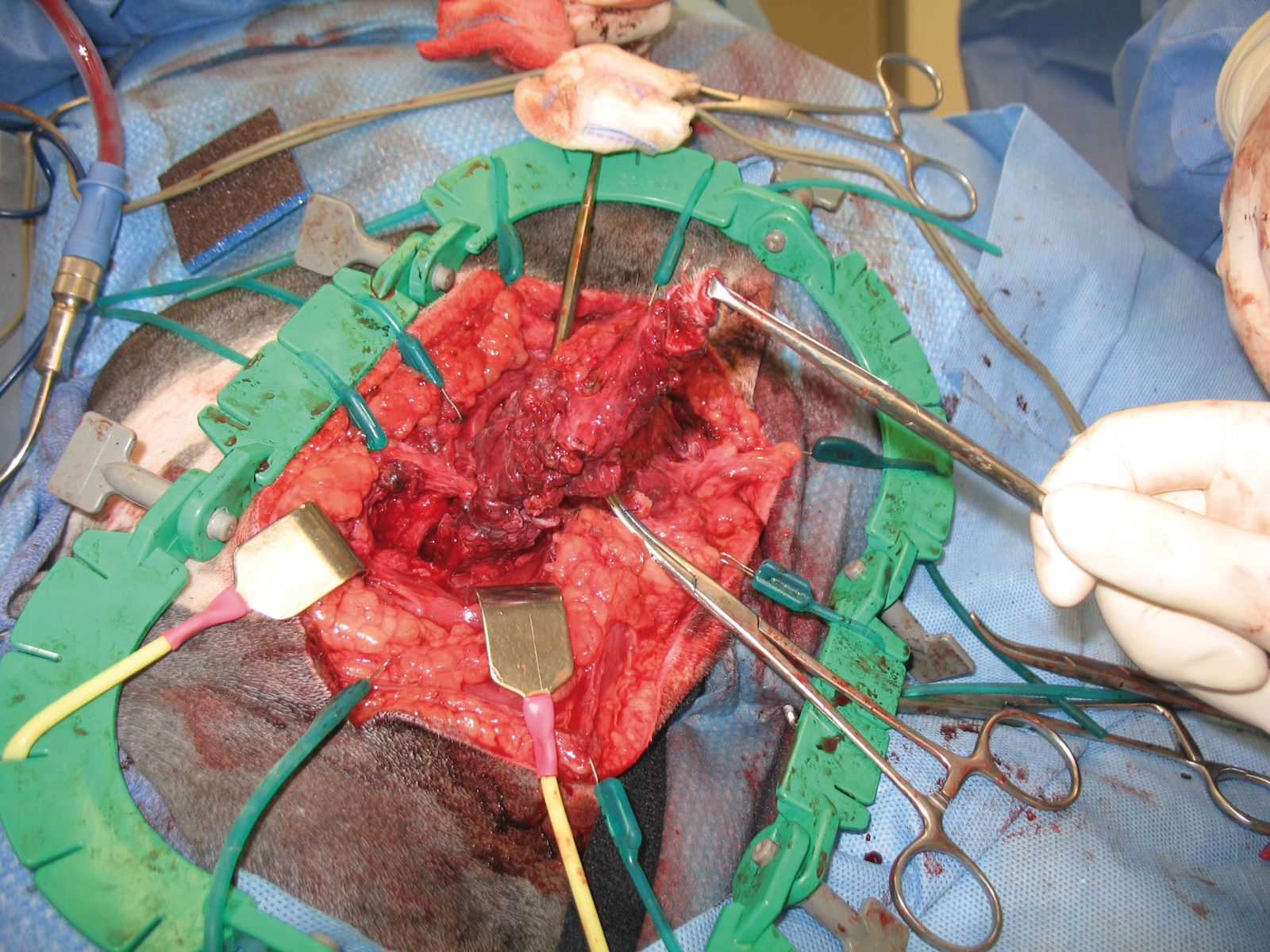

A large area should be prepped for surgery, since the path(s) of penetration may deviate in the deeper tissues. The surgeon should be prepared to enter the abdomen or chest if necessary. Entry and exit wounds are opened, the underlying tissue is visualized, and path of injury is followed to its deepest extent, debriding damaged tissue along the way (Figure 3) [2]. In bite wound victims, one can commonly insert a hemostat into one wound and exit it out a number of others due to avulsion of skin that has occurred (Figure 3a). When there are multiple bite wounds in an area, one longer incision can be made to access the tissue deep to all of these bite wounds at once.

An instrument or rubber tube can be inserted into the wound tract to aid dissection. It is common to see increasing tissue damage as one follows the tract into deeper tissue (Figure 3). Walls separating areas of dead space should be broken down and tissue that is clearly necrotic excised – no matter how much the clinician may wish to save it – as leaving it perpetuates inflammation, blocks granulation, and increases the risk of infection. Signs of necrosis include abnormal color and consistency (dry necrotic tissue is dark/black and leathery; moist necrotic tissue is yellow/gray/white and slimy) and lack of bleeding when cut (assuming the patient is not hypothermic or hypovolemic). Debridement should be continued until viable tissue is reached. Guidelines for debridement of tissue with uncertain viability are in Table 1.

| “When in doubt, cut it out” if: | “When in doubt, leave it in” if: |

| removal is compatible with life | removal is incompatible with life |

| And | Or |

| there is only one opportunity to access and assess the tissue | there will be multiple opportunities to access and assess the tissue |

| And/Or | And |

| there is plenty of residual tissue so it will not be missed | the tissue will be valuable for later wound closure |

| Examples – damaged muscle deep in a wound; damaged spleen, jejunum, liver lobe, or lung lobe | Examples – damage to the one working kidney; damaged skin on a distal limb, where there is limited skin available for repair |

* Uncertain viability i.e., it is unclear whether the tissue will survive; it has some signs of viability and some signs that it is dying; clearly necrotic tissue should be removed.

Debridement is followed by copious lavage at 7-8 psi, which maximizes removal of debris and bacteria while minimizing tissue damage (Figure 4). Avoid pressurized lavage on fragile organs. Lavage of abdominal and thoracic cavities should be with sterile saline alone, but antiseptic solutions (not scrubs) can be used in subcutaneous tissues and muscle. Appropriate concentrations are 0.05% chlorhexidine solution (e.g., 25 mL of 2% chlorhexidine + 975 mL diluent) or 0.1%-1% povidone-iodine solution (e.g., 10 mL of 10% P-I + 990 mL diluent for 0.1%; 100 mL of 10% P-I + 900 mL diluent for 1%).

The debrided wound is left open and managed with moist wound healing [10] and serial debridement and lavage as needed. The wound is closed once the veterinarian is confident it is free of contaminants, necrotic tissue, and unhealthy tissue that might necrose later. If a wound must be closed before that point, a drain (preferably a closed, active suction drain) should be placed and covered with a bandage [11]. Post-operative care also includes fluid support as needed, analgesics, and good nutrition with a recovery diet to support the healing process. In highly compromised patients, consider placing a feeding tube during anesthesia to ensure adequate nutrition during recovery.

More conservative debridement and lavage may be considered for superficial and/or low severity non-abdominal penetrating injuries [12] [13]. For example, damage caused by a single, non-tumbling, non-deforming bullet passing only through skin and muscle may be limited to the permanent cavity since these elastic tissues can handle a lot of cavitation energy. A similar effect may be created by penetration with a sharp, smooth, clean foreign body.

Wounds to the abdominal or thoracic cavity

- There is a high risk of intestinal damage

- Untreated intestinal perforation is life-threatening, and clinical signs may not be apparent until there is full-blown septic peritonitis and septicemia

- Normal test results do not exclude internal injury (see above)

- Intestines are constantly moving, so the damage cannot be reliably found just by following the wound tract through the body wall

While this “default celiotomy” approach will result in some negative abdominal explores, the risk-benefit ratio is squarely on the side of surgery even if penetration is unproven [2] [5] [13] [15].

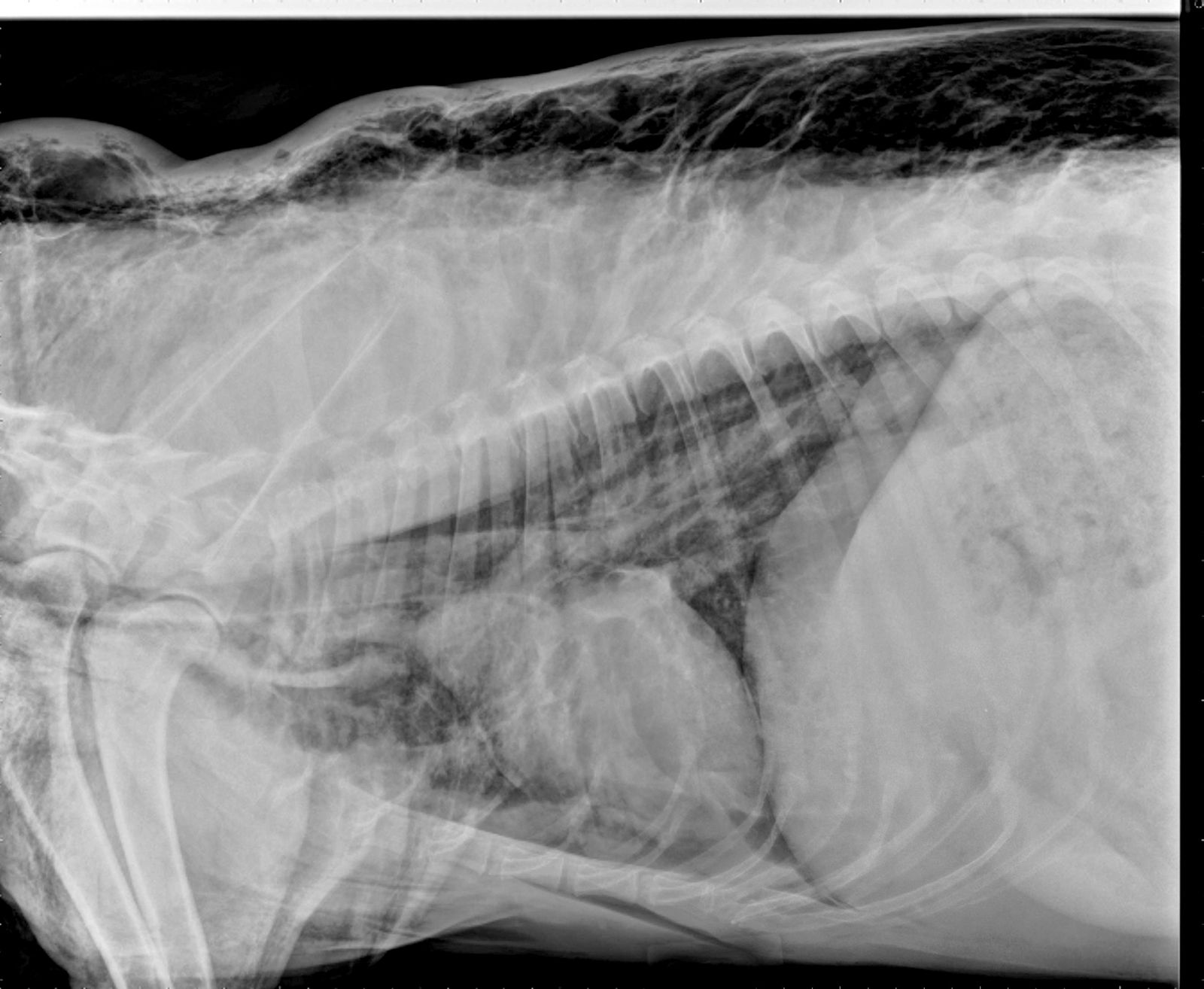

Penetrating wounds over the thorax are opened, debrided, lavaged, and explored as for any wound; this may take the surgeon into the thoracic cavity. However, unlike an abdominal penetration, full exploration of the thoracic cavity is not the default, as:

- The rib cage makes it challenging for penetrating objects that are not correctly aligned to enter the chest

- The elasticity of the lung makes it less susceptible to penetration and associated collateral damage

- The lungs are not laden with bacteria

Removal of penetrating objects

Use of antibiotics

The question can be asked: are antibiotics indicated for all penetrating wounds? Such wounds are contaminated with bacteria and debris, and the risk of infection increases with the amount of tissue damage and vascular compromise. While antibiotics are typically given during surgery, proper debridement and lavage are pivotal to minimizing the risk of contamination turning into infection; antibiotics do not replace the need for local wound care [3] [20]! Antibiotics can be stopped post-operatively for shallow, minimally contaminated wounds surgically converted to clean [3] [19]. Post-operative antibiotics are clearly indicated in patients with extensive tissue damage, open joint or fracture, sheared bone, SIRS, immunocompromise, and actual infection [1] [2] [19] [21]. In between these two groups, the decision is less clear cut and must be tailored to the individual, factoring in the need to avoid unnecessary use of antibiotics due to multi-resistant bacteria. For patients with infected wounds, antibiotic choice is ultimately based on aerobic and anaerobic cultures. Culture of a piece of tissue cut from deep in the wound is the most reliable, followed by culture of purulent material; culture of the wound surface is least desirable due to surface contaminants.

Conclusion

Recognition of the iceberg effect is important for thorough treatment of penetrating wounds. Early, pre-emptive debridement and lavage of penetrating wounds prevents the development of SIRS or sepsis several days after injury. If penetration of the abdominal cavity cannot be ruled out, the abdomen should be explored due to the high risk for intestinal perforation.

References

- Morgan M, Palmer J. Dog bites. Brit Med J 2008;334:413-417.

- Campbell BG. Dressings, bandages, and splints for wound management in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2006;36:759-791.

- Campbell BG. Bandages and drains. In: Tobias KM, Johnston SA (eds). Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal (1st ed) St. Louis: Elsevier, 2012;221-230.

- Tosti R, Rehman S. Surgical management principles of gunshot-related fractures. Orthop Clin North Am 2013;44:529-540.

- Fullington RJ, Otto CM. Characteristics and management of gunshot wounds in dogs and cats: 84 cases (1986-1995). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1997;210:658- 662.

- Lisciandro GR. Abdominal and thoracic focused assessment with sonography for trauma, triage, and monitoring in small animals. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2011;21:104-122.

- Kirby BM. Peritoneum and retroperitoneum. In: Tobias KM, Johnston SA (eds). Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal (1st ed) St. Louis: Elsevier, 2012;1391-1423.

- Bartels KE, Staie EL, Cohen RE. Corrosion potential of steel bird shot in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1991;199:856-863.

- Barry SL, Lafuente MP, Martinez SA. Arthropathy caused by a lead bullet in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008;232:886-888.

- Khanna C, Boermans HJ, Woods P, et al. Lead toxicosis and changes in the blood lead concentration of dogs exposed to dust containing high levels of lead. Can Vet J 1992;33:815-817.

- Morgan RV. Lead poisoning in small companion animals: an update (1987-1992). Vet Hum Toxicol 1994;36:18-22.

- Campbell BG. Surgical treatment for bite wounds. Clin Brief 2013;11:25-28.

- Brown DC. Wound infections and antimicrobial use. In: Tobias KM, Johnston SA (eds). Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal (1st ed) St. Louis: Elsevier, 2012;135-139.

- Nicholson M, Beal M, Shofer F, et al. Epidemiologic evaluation of postoperative wound infection in clean-contaminated wounds: A retrospective study of 239 dogs and cats. Vet Surg 2002;31:577-581.

- Gall TT, Monnet E. Evaluation of fluid pressures of common wound-flushing techniques. Am J Vet Res 2010;71:1384-1386.

- Pavletic MM, Trout NJ. Bullet, bite, and burn wounds in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2006;36:873-893.

- Holt DE, Griffin GM. Bite wounds in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2000;30:669-679, viii.

- Shamir MH, Leisner S, Klement E, et al. Dog bite wounds in dogs and cats: a retrospective study of 196 cases. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med 2002;49:107-112.

- Griffin GM, Holt DE. Dog-bite wounds: bacteriology and treatment outcome in 37 cases.J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2001;37:453-460.

- Risselada M, de Rooster H, Taeymans O, et al. Penetrating injuries in dogs and cats. A study of 16 cases. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2008;21:434- 439.

- Scheepens ET, Peeters ME, L’Eplattenier HF, et al. Thoracic bite trauma in dogs: a comparison of clinical and radiological parameters with surgical results. J Small Anim Pract 2006;47:721-726.

- Jordan CJ, Halfacree ZJ, Tivers MS. Airway injury associated with cervical bite wounds in dogs and cats: 56 cases. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2013;26:89-93.

Bonnie Campbell

DVM, PhD, Dip. ACVS

Dr. Campbell received her DVM and PhD degrees from Cornell University. She completed a small animal surgical residency at the University of Wisconsin and is a Diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Surgeons. Dr. Campbell is now a Clinical Associate Professor of Small Animal Soft Tissue Surgery at Washington State University, with particular clinical interests including wound management and reconstructive surgery. She gives continuing education programs both nationally and internationally and has served as president of both the Society of Veterinary Soft Tissue Surgery and the Veterinary Wound Management Society.

Other articles in this issue

Share on social media